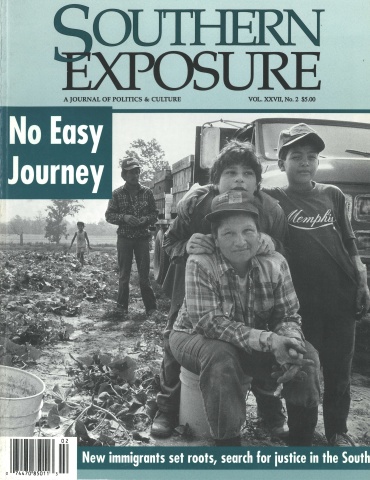

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

In the rural migrant camp where Carmelo Fuentes bunked, workers did not hear the weather advisories warning against overexertion in the 90 plus degree heat. Even if he had, Carmelo would have gone to work. Three weeks after starting, he and his co-workers had been putting in 10-12 hour days picking crops near Clinton, N.C. Carmelo did not complain about the long hours. An hour at minimum wage earned him more than a day’s work in his hometown of San Luis Potosi, Mexico.

On July 5th, Carmelo phoned home and spoke with his disabled sister, Yolanda. He told her that he almost had the money for the surgery that would restore her vision. His father, Porfirio, took the phone. Hearing that his son had just worked seven days in a row, Porfirio begged Carmelo to take a day off to rest. I’m fine, Carmelo reassured him, besides there’s too much work to do.

Five days later, as the heat wave continued, Carmelo collapsed in a tomato field. His coworkers dragged him into the shade of a tree to cool off. They told the foreman, but hours passed before an ambulance was called. By then, Carmelo was comatose from heat stroke and dehydration.

Porfirio, after being notified of his son’s condition, braved a long trip, taking buses and hitching rides, until he found the University of North Carolina Hospital where his son lay in respiratory intensive care. Months later, Porfirio remained by Carmelo’s bedside, helping nurses put lotion on his son’s legs and adjusting the tubes that provided him oxygen and nourishment.

As he recounted Carmelo’s sad tale, the elderly man grasped his son’s head firmly between his callused hands and planted a kiss on his forehead. “It was wrong. They ought to have called an ambulance immediately, but they didn’t. Now the foreman has disappeared and no one knows where to find him.”

In October, Porfirio and Carmelo flew home to San Luis Potosi, the timing of his return coinciding, ironically, with the end of the farm labor season. Physicians do not hold out much hope for improvement in Carmelo’s condition.

Advocates for farmworkers’ rights say the Fuentes case, originally reported by David Shulman in The Chapel Hill News, is only the latest example of the human costs from the harsh working conditions endured by the 344,000 mostly Latino men and women who labor on North Carolina’s farms. The poorest paid of U.S. workers, farm laborers are exempt from most workplace legal protections, and their constant exposure to pesticides makes farm labor one of the most hazardous of U.S. jobs. When overwork and unsanitary living conditions are added to the mix, it becomes easier to understand why the average farmworker has a life expectancy of only forty-nine years.

“People say you earn good money here; that it’s the land of dreams,” said Wilfredo Rivera, a former staff member of the North Carolina Farmworkers Project. “But they are really not looking at the conditions. During the season, farmworkers are often in the fields seven days a week for 10 or 12 hours a day. They live in isolated places, with the worst living conditions, run-down houses, no transportation or phone. It’s like you’re a prisoner.”

Justino Guzmán, an immigrant from Zacatecas, Mexico, who now lives in the Research Triangle and works for a janitorial company, worked in the fields his first year after entering the U.S. Guzmán described his summer picking cucumbers near Newton Grove as the hardest work he’d ever done. “It’s stoop work — at the end of the day sometimes I couldn’t stand up after hours of crawling like a baby.”

In 1991, when Guzmán worked the cucumber fields, he earned $25 a day. Even today, with a slightly higher minimum wage, no worker interviewed for this story reported earning more than $56 for a 10-hour day. And that’s before deductions for taxes and debts to the crew leader.

In the last decade, North Carolina’s agricultural industry has grown rapidly. In 1995, the state ranked second in the nation for net agricultural profits, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But the vertical integration of agribusiness has ensured that most of the profits are kept by food processors and large factory farms, at the expense of small farmers and the laborers who tend and harvest the crops.

The irony is that although migrant labor is vital to the profitability of North Carolina agriculture, most farmworkers cannot afford to eat the food they pick. In fact, malnutrition is higher among farmworkers than any other sub-population in the country.

Plantation Economics

One of the stumbling blocks for farmworkers is that federal law has exempted agricultural workers from wage and hour laws that protect other U.S. workers. For example, David Craig, of the Wage and Hour Division at the North Carolina Department of Labor, explained that employers of farmworkers are not required to pay them for overtime, and there are no requirements that workers be given breaks during the workday.

Whether farmworkers are paid at a piece rate or by the hour, the pay rate is not supposed to fall below the federal minimum wage of $5.15 per hour, which applies to citizens and non-citizens alike. However, on small farms, Craig said, farmworkers are not guaranteed minimum wage. He described such “small” farms as those that employ 500 or less man-days of farm labor per quarter, or the equivalent of 7-8 workers for 5 days/week.

The state Department of Labor employs 30-35 wage/hour investigators statewide. In addition to their other work, these individuals are responsible for ensuring that growers comply with wage and hour laws. But the sheer number of farms employing migrant labor — estimated at nearly 22,000 in 1992 — means that inspectors are able to visit only a tiny percentage of workplaces in a given year. Craig said that the department relies on a “mostly complaint-driven” system of enforcement.

But with a mostly-foreign workforce that lacks immigration papers or command of English, complaints are rare and abuses are common, says farm labor organizer Ramiro Sarabia. Some growers, Sarabia says, hire workers at a piece rate, and then convert to hourly rates for reporting to the government. They calculate worker’s minimum salaries based on an eight-hour day, even though the workers actually work longer hours. As a result, many farmworkers are unsure how their pay and deductions are figured.

Unscrupulous middlemen frequently take advantage of recently immigrated workers. The typical situation, according to Sarabia, is a cucumber grower strikes a deal to pay such a “crew leader” 85 cents per bucket for picked cucumbers, of which the crew leader keeps 20 cents, and pays each farmworker 65 cents per bucket. “It’s a pretty good deal for a crew leader. If he brings 30 workers, and gets to keep one dollar an hour for each, he gets paid $30 per hour!” Crew leaders often also take deductions from workers’ paychecks for services provided such as rent (if housing is not provided by the grower), food, transportation, or debts charged to workers for finding them a job.

Child labor in the fields used to be common. “I worked with kids 7-8 years old. They were the family of the crew leader. Now, I know that it’s illegal for kids to work—but at the time I didn’t think anything of it,” recalled former cucumber picker, Justino Guzmán.

Reforms in state law now prohibit farms from employing minors under 14, but enforcement is weak, and for agricultural labor there are fewer protections for 14- 18-year-olds than in other occupations. Nationally, the number of youths under 17 in the migrant farm worker population has doubled since 1990. In North Carolina’s cucumber fields, however, most farmworkers are single men, for the simple reason that farmers in the H2A program, which supplies the bulk of cucumber workers, perceive men to be the most productive pickers, and less trouble to house than families.

Alfonso, a 22-year-old migrant from Oaxaca, Mexico, described his work as he took a break from socializing at a Farmworker Festival near Newton Grove, N.C. Alfonso (who declined to give his last name) said he earned $5 per hour in tobacco, and worked six days a week at 9- 10 hours a day. “I would prefer more pay and fewer hours, but I’m just doing what I’m told. Some workers complained to the crew leader about the pay, but he says he can’t pay us more.” Even so, Gonzalo said he was earning far more than he had in Mexico, where he had spent three-quarters of his bricklayer salary just to pay the rent.

Stan Eury, Executive Director of the North Carolina Growers Association, has a different perspective on farm working conditions. “We educate [H2A] workers on how to maximize their earnings. I’ve seen workers make $500 a week at the height of the season. H2A workers get free housing. Agricultural workers are treated better than ordinary citizens under the law.”

“Living in Squalor”

Growers have historically provided housing for migrant workers in order to ensure an adequate workforce during the season. Farms are often too remote to walk to town, and most migrants lack transportation. And due to federal reforms enacted in 1986, housing standards have been tightened. The weak link in North Carolina, as in many other states, is poor enforcement of the law.

A New York Times exposé by Steven Greenhouse, published in May 1998, concluded that while the economy was booming in the 1990s, “more farmworkers than ever are living in squalor.” Part of the reason, according to Greenhouse, is that federal spending on migrant housing plummeted in the last 30 years. In 1998, the government spent only 40 percent of what it spent to house migrants in 1969. The Housing Assistance Council, a Washington, D.C.-based watchdog group, estimates that 800,000 current U.S. farmworkers lack adequate housing.

Rather than upgrading existing buildings, Greenhouse noted that many growers responded to the 1986 housing reforms by no longer offering housing. As a result, many migrants crowd into cheap hotel rooms, while others sleep in cars or on roadsides.

One positive aspect of the H2A program in North Carolina has been more regular housing inspections on those farms that employ official “guestworkers.” To date, 1,328 growers have registered with the state for housing 16,046 migrant workers, but the N.C. Department of Labor estimated that many more of the state’s 22,000 farms that employ farmworkers house migrants, yet defy the law and remain unregistered.

Eury said growers in the H2A program who do comply with the housing laws would like to see more inspections so that competing farmers are forced to bring their housing up to standard, noting that, “those farmers who improve their housing are at a competitive disadvantage compared with farmers who don’t.”

Regina Luginbuhl, of the Agricultural Safety and Health Office in the N.C. Department of Labor, said that the task of inspections falls to four full-time and four temporary inspectors hired each growing season. At last count, only one of the eight speaks Spanish.

Justino Guzmán, the former farmworker who “came to the U.S. to find a better life,” ended up in substandard housing the year he picked cucumbers near Newton Grove. He described bedrooms without beds where four men slept in each room, and a house with no heat, no air conditioning, and no stove. “We cooked on a camp stove. We slept on the floor, without even a rug. I remember there was a dog sleeping outside on a pad, and we talked about stealing the pad.”

While heating and air conditioning are not legally required in migrant housing, growers must supply beds and stoves. A migrant camp can meet state standards, while still providing only minimal washing facilities. In North Carolina, one washtub for 30 workers meets requirements, but hardly seems adequate for workers to comply with pesticide safety recommendations that they wash their clothes after a day in the fields. In fact, for lack of changes of clothing, many workers wear the same contaminated clothes day after day.

Sanitation has proven to be a serious problem. A University of North Carolina study published in 1992 found that 44 percent of N.C. migrant camps tested had contaminated water supplies. Field sanitation regulations are also now established by federal law, but Luginbuhl said compliance with these regulations remains poor in North Carolina, noting that inspectors “rarely find port-a-johns and hand wash facilities” near the fields.

Hazardous Harvest

Poor sanitation, hazardous working conditions, and poor access to health care are among the explanations why farmworkers, as a population, have abysmal health. Infant mortality rates among farmworkers are a striking 125 percent higher than rates for the general population. The 1992 UNC study cited above found that 86 percent of N.C. farmworkers tested had intestinal parasites — a situation that reflects sanitation both in their country of origin and U.S. living conditions.

Although the federal government subsidizes migrant health clinics that offer low cost or free health care, for lack of information or transportation most farmworkers never receive health services. If every farmworker sought these services, the federal program would be overwhelmed — its funding is estimated at $14 per farmworker.

Poor farmworker health is related to these workers’ occupational risks. Agricultural workers constitute only 3 percent of the nation’s workforce, but account for 11 percent of workplace fatalities. Over the last 40 years, agricultural injury and death rates have fallen at only a third the rate of improvements in other hazardous occupations like mining and construction.

For farmworkers, the major cause of illness is poisoning from the 1.2 billion pounds of pesticides that are now used on virtually all commercial crops. A 1995 report by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found that pesticides were responsible for more than 300,000 illnesses and 1,000 deaths among U.S. farmworkers each year.

Children are especially vulnerable. The United Farm Workers, a union of farmworkers, blames pesticide exposure for an outbreak of cancer among children in West Coast agricultural communities.

Migrant health specialists report that pesticide poisoning often happens gradually, and causes lingering health conditions ranging from allergies and respiratory problems to serious nervous system disorders and cancer. Many workers confuse early symptoms of pesticide poisoning, such as fatigue, nausea or dizziness, with other afflictions such as the flu or too much sun exposure.

Although rarely enforced, new federal standards were adopted in 1993 that require workers who handle chemicals to take pesticide safety training classes. However, health workers who offer the classes at migrant clinics estimate the demand for training is far higher than they can meet.

Gonzalo, a farmworker who has taken a training class, reported that he now uses a mask and protective gear to apply pesticides, and wears gloves and long sleeves to work in the fields. He also said he tries to wash his hands and arms before eating. “I’m not afraid to work with pesticides as long as you don’t drink them and die!” he exclaimed. “But I’ve seen some guys who would just pour it on their skin, then they would get sick and throw up.”

At a safety class in Alamance County, a bilingual health worker explained pesticide risks, and cautioned workers to avoid working in fields that had just been sprayed until a minimal waiting period had passed. One farmworker raised his hand. “And what do we do if we’re ordered into the field before then?” The health worker sighed and went over the procedures for filing a grievance with the Department of Agriculture in Raleigh. “No one is going to do that,” the farmworker scoffed.

In an October 1998 interview, Sharon Preddy, of the N.C. Department of Agriculture, said the number of pesticide field inspectors for farms was upgraded during the past year from four to seven. None of the new inspectors speak Spanish either, according to Preddy, who said the department failed to find “qualified” bilingual job candidates. However, she said a bilingual staff person had just been hired to work in the Raleigh office, and would be training the staff in rudimentary Spanish. “It’s way past time, but at least we are making some progress,” she noted.

Inspectors are mainly concerned with “restricted use” pesticides which 26,000 N.C. growers are certified to use. In the first nine months of 1998, 451 farms were inspected, according to Preddy, twice the number inspected in the same period in 1997. At this rate, however, it will take about 43 years for state inspectors to visit all N.C. growers certified as pesticide users.

In response to pressure from farmworkers and advocates, the N.C. Department of Labor recently began a new program that will dispatch inspectors to a site within 24 hours of a complaint alleging chemical exposure.

In 1996, 198 complaints resulted in 61 write-ups for non-compliance and 41 fines. But, in an indication of how the program has fallen short of its goal to engage workers, only a small percentage of complaints have come directly from farmworkers.

When discovered, violations of pesticide regulations seldom result in more than a slap on the wrist. The average fine was $370. Interestingly, while commercial users and homeowners face a maximum fine of $5000 for misuse of pesticides, North Carolina growers, who wield far more clout in the legislature, face a maximum annual fine of only $500.

Occasionally farmworkers take risks to get out of abusive situations. A North Carolina cucumber grower was left without a workforce in June 1998 when about 75 H2A workers abandoned his farm in the middle of the night. The men later said that the grower’s foreman had worked them for over 14 hours with only a half-hour lunch break, and refused to allow two sick workers to stop picking. Fearful of deportation, the men declined to file a grievance, and went to work for another grower.

Farmworkers face an uphill struggle to change conditions. But, the changes cannot come rapidly enough for Aaron Fuentes, the older brother of Carmelo, the man who remains in a coma following a heatstroke in a Clinton, N.C. tomato field. Like Carmelo, Aaron came to North Carolina last summer to work with the H2A program. After months of daily vigils by Carmelo’s hospital bed, he and his father, Porfirio, looked forward to rejoining their family in Mexico.

Asked if he would come back to the United States next year to do farmwork, Aaron frowned. “No, I will never come back here. Not after this. It’s not only the sun, it’s the pesticides, the tobacco sickness.’’

Tags

Sandy Smith-Nonini

Sandy Smith-Nonini is an adjunct assistant professor of medical anthropology at the University of North Carolina Chapel-Hill and a former investigative reporter for Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South.