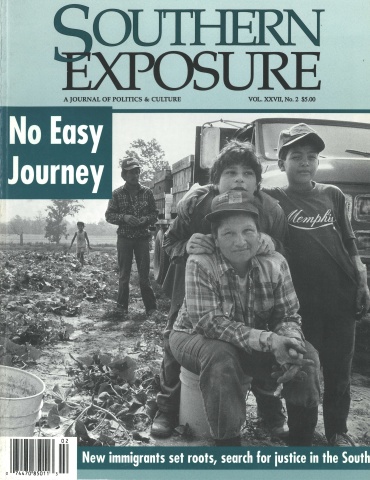

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

While many consumers believe U.S. agriculture is largely mechanized, 85 percent of U.S. fruits and vegetables are tended or harvested by hand. Those hands belong to farmworkers, who are among the most underpaid and exploited of U.S. workers, their lives virtually invisible to most Americans. This is particularly true in the antiunion South where agribusiness has grown in recent years by recruiting the cheapest and most pliable workers, which today are mostly Spanish-speaking immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

In North Carolina, however, a bold new organizing drive led by the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), an Ohio-based farmworkers union, is challenging this 1990s version of a plantation economy. A handful of former farmworkers affiliated with FLOC have been working in southeastern North Carolina to organize cucumber pickers working for the farmers of “growers” of Mount Olive Pickle Co., the second largest pickle producer in the United States.

Baldemar Velasquez, FLOC’s president and founder, places FLOC’s campaign to “organize the South” as part of a wider social movement. “There is a new Latino labor force all over the South that will be the foundation of the next civil rights movement in the U.S. — a movement that is going to have a brown face.”

To date, more than 2,100 cucumber pickers have signed cards authorizing the union to represent them, but Bill Bryan, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Mt. Olive Pickle, maintains that since his company does not hire farmworkers, he has no responsibility for their working conditions. He has refused to encourage growers he buys from to recognize the union.

“Everyone takes advantage of a migrant worker,” said Ramiro Sarabia, who heads up FLOC’s North Carolina campaign from an office in Faison, N.C. “The wages are low. Some even get paid less than minimum wage. And everywhere you look you see bad conditions. A union is the only way we’re going to improve conditions. FLOC is going to be here a long time, maybe forever.”

In Ohio and Michigan, after two decades of struggle, FLOC has achieved fairer working conditions for more than 7,000 farmworker members. FLOC is most well-known for its seven-year boycott against Campbell Soup. The union eventually won 3-way contracts between Campbell Soup, vegetable growers, and farmworkers. FLOC has also developed a collaboration between Ohio’s state government and the private sector on a pool of funds to subsidize housing improvements for farmworkers.

Asked why the union targets food processors rather than growers, Sarabia put it simply, “They are the ones who have the money.” He explained that many growers contract directly with processors, who supply them with seeds and even buy the crop in advance before the seeds go in the ground.

The new FLOC campaign has been endorsed by the North Carolina Council of Churches and is assisted by volunteers from the ecumenical National Farm Workers Ministry. Each of these groups is seeking to build community support through religious organizations. In rural North Carolina, where many congregations side with local growers and companies than the predominantly immigrant farmworkers, support for the FLOC campaign has been slow to materialize. FLOC supporters have only recently begun to build support among urban religious and community groups.

In June of 1998, FLOC organized a 4-day march from Mt. Olive, North Carolina, to Raleigh where a rally at the capitol drew attention to farmworker concerns. The march, which took place in 90-degree heat, attracted only a small contingent of supporters for most of the distance, although over 150 people, including a handful of farmworkers, demonstrated in Raleigh. A highlight of the event was a speech by J. Joseph Gossman, Raleigh’s Catholic Bishop, who pointed up the distinction between the charity work that many churches engage in and struggles for justice.

“Basic justice demands that people be assured a minimum level of participation in the economy,” said Bishop Gossman. “It is wrong for a person or group to be excluded unfairly. . . . Farmworkers need to be partners around the table with growers (and) corporations so that the common good of all is reached.”

The New Latino Face of Farm Labor

The large numbers of workers who earn low wages and endure marginal living and working conditions have proven to be a boon for North Carolina growers who have experienced an economic squeeze as food processors have increased corporate control over products from seed to marketplace.

Cheap labor costs have enabled North Carolina’s agricultural industry to become the second most profitable in the U.S. Yet, food processors rake in the bulk of income from sales, while growers keep about a third, leaving farmworkers with only about eight cents of every food income dollar in North Carolina. In contrast, in California, where farmworkers have organized, farmworkers keep approximately 18 cents of every food income dollar, according to the 1993 Commission on Agricultural Workers Survey.

In all, more than 340,000 farmworkers work in N.C. annually, of which about 40 percent are migrant laborers — those who work in different states over the course of a year. But the demographics have changed since the 1980s when most migrant farmworkers were Black. Today, 90 percent of farmworkers in the state are Latino.

Since 1990, North Carolina growers have begun recruiting large numbers of Spanish-speaking “guestworkers” through the federal H2A program, which provides temporary work visas for laborers who cultivate and harvest crops during the growing season — typically from May to late October.

One Former Farmworker’s Story

Often farmers or “growers” do not deal with farmworkers directly, but rather with middlemen known as “crew leaders.” Some of the worst abuses and working conditions occur when immigrants unfamiliar with local work arrangements fall under the control of an unscrupulous crew leader.

The experience of Ramón Berosa, who uses the name of his dead grandfather for this article, illustrates a typical situation encountered by migrant workers. Berosa came to North Carolina in 1996 from Rio Bravo Tamaulipas, Mexico, where typical wages for unskilled workers were the equivalent of $2 per day. “I came to the United States to work and make enough money to return to Mexico and start a small food store.”

The first “coyote” Berosa hired to guide him into the U.S. and find work took his $800 and abandoned him on the U.S. side of the border. He then paid a second “coyote” to help him find work, and that man “sold” him to a crew leader who landed him a job on a North Carolina cucumber and sweet potato farm. As a result, Berosa began work for the crew leader $500 in debt.

“Once I subtracted my debt payment, rent and transportation from my weekly paycheck, all I would have left was $40. It took a year to pay him off,” Berosa recalled.

“Some left because they were mad at the crew leader for working them too hard and paying them less than the minimum wage. But we were guarded; I didn’t dare try to leave. None of us had cars, and his spies reported on us if we went to talk to newcomers [to the farm]. He kept me like that for 2 years. I never sent any money to my family during that time. They had been running a small food store, but they lost the store because I couldn’t send them any money.”

Berosa learned about FLOC last summer when he went looking for medical assistance for a farmworker with bad kidneys. A friend put him in touch with Ramiro Sarabia, who found his friend a doctor. After learning more about the union effort, Berosa decided to quit farm work and work full-time as an organizer for FLOC.

An Anti-Union Climate

Existing U.S. labor laws offer few protections to farmworkers, who are specifically excluded from the National Labor Relations Act. And, as a “right-to-work” state, North Carolina law permits employers to hire non-union workers, even in a workplace where workers have a union contract. The state’s history of hostility to labor poses a special challenge to FLOC’s campaign.

Mt. Olive Pickle CEO Bill Bryan said in a phone interview that FLOC’s pressure on his company is unfair. “Our company has been targeted solely because of our name recognition. We deal in free enterprise. Our only moral responsibility is to treat suppliers as we would like to be treated, which is to allow them to make their own decisions about unionization.”

Bryan, who said that his company had been growing and expanding its market into the Midwest, hinted that Mt. Olive Pickle could look elsewhere to buy its cucumbers. “We buy fewer pickles in North Carolina than we did a few years ago. We buy according to market demand and where the product is most available.”

Stan Eury, Executive Director of the North Carolina Growers Association, said unionization would hurt growers. “We’ve heard from farmers in the Midwest that the union was the worst thing that’s ever happened to them. After FLOC got its contract, production went down, and it may go down here if workers unionize. Pickles are not a high profit crop. I think many growers would get out of the business of cucumber growing if workers unionize.”

In contrast, Velasquez claims that growers, as well as farmworkers, have benefited from the Midwest contracts. He says that since unionization, growers now receive a higher price for their crops from processors.

In Ohio, for example, the price for 100 pounds of “No. 1” cucumbers (the smallest and most profitable) was $26 in 1998, up from $14.50 in 1986. The 1998 price in North Carolina for the same quantity of No. l’s was $17. Velasquez also cites surveys showing that production is higher in unionized areas of the Midwest than before the FLOC campaign.

Wally Wagner, a cucumber grower for Vlasic in Ohio, supports Velasquez’s position. “The farmworkers with FLOC are just looking for a fair shake. We didn’t find that unionization threatened our business.” He credited the FLOC effort for helping farmworkers get better pay and lobbying public and private interests to contribute to a fund for better farmworker housing. He said the union has worked with both growers and processors to improve productivity, which he thinks is better than a decade earlier.

Virginia Nesmith, Executive Director of the National Farm Workers Ministry, said the anti-union sentiments of many growers translates into a climate of fear for workers. “Workers who support the union often experience an intense level of intimidation. Public support is very important to create a climate in which workers can come forward.”

Wilfredo Rivera, formerly with the North Carolina Farmworker Project in Benson, agreed, noting that organizers of any kind are not welcome in farmworker camps — which are usually located on the property of growers. “Many camps don’t even allow visitors. The owners put up ‘No Trespassing’ signs, even though it’s a violation of the workers’ tenancy rights,” explained Rivera. “Growers in many areas have a lot of influence over the local sheriff’s department. They’ll arrest you for visiting a farmworker camp.”

In fact, H2A contracts adopted by the North Carolina Growers Association assert that owners have the right to restrict access to farmworker camps.

Last June, attorneys for Farmworker Legal Services were expelled from a work camp on the farm of Cecil Williams, a Nash County grower who threatened to have them arrested for attempting to meet with an injured worker on the property. In August, FLOC president Baldemar Velasquez, Sarabia, and two other organizers challenged this policy by visiting the same camp.

About an hour after FLOC’s arrival, two law enforcement officers broke up a meeting between the organizers and about 20 local workers. When they refused to leave voluntarily, the FLOC organizers were arrested. Although a magistrate threw the case out, the local sheriff later told organizers he would continue arresting anyone who growers accuse of trespassing.

Building Community Support for a Boycott of Mt. Olive

In October 1998, around 100 people, including Velasquez, the FLOC organizers, and a contingent of twenty-five farmworkers gathered on Duke University’s campus in Durham to plan the next steps in the campaign. Since the Mt. Olive Pickle Co. continues to reject talks, organizers project that a center point of the campaign will be a boycott of Mt. Olive Pickle products throughout the Southeast, where the company’s market is based.

The campaign’s immediate focus is to build a community network of support for the farmworker struggle. The involvement of churches, universities, and community groups were critical to the success of the FLOC campaign against Campbell Soup in the 1980s. Velasquez said FLOC learned in the Midwest campaign that strikes are not effective organizing tactics for farmworkers. In the end, he said, it was the combination of the boycott against Campbell Soup and the moral pressure from the surrounding community that forced company executives to sit down at the bargaining table with farmworkers and growers.

Velasquez says that the FLOC strategy, in contrast to many labor unions, is to “make a permanent commitment to a community.” In North Carolina, that kind of long-term vision might be what is needed to win a victory. But if Velasquez is right about his prediction that the time is ripe for a “new civil rights movement,” winning may well depend less on economics than on the strength of the public’s moral stand in support of adequate housing, decent wages, and safe working conditions for farmworkers.

Ramon Berosa may be the kind of person who will help lead such a movement. Up until August, Berosa held a decent paying, if dangerous, job loading tobacco on large trucks. Recently married, with an 18-month-old child, and a new baby on the way, he had good reason to hold on to his job, but he took a cut in pay to work for FLOC.

“It’s true that I earn less now with FLOC,” he admitted. “But I like to work for people. It’s not just a matter of money. No one’s going to get rich doing this, but that’s not the point. This work makes me feel good.”

Seed to Table: The Story of Mt. Olive Pickles

The Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) is organizing N.C. farmworkers in an attempt to negotiate a three-way contract with farmworkers, growers, and the Mt. Olive Pickle Company. Mt. Olive argues that it is only a consumer of farm products and has no direct dealings with the farmworkers that grow its pickles. FLOC argues that the company plays too large a role in the growing cycle to escape responsibility. Readers can find the process here, from seed to table.

1. Growers usually contract to sell cucumbers to middlemen who operate grading stations. The middlemen agree to pay the grower based on a contract it has with Mt. Olive. Mt. Olive also provides cucumber seed to its grading stations.

2. To escape poverty at home, Mexican and Central American workers pay recruiters a fee upwards of $100 to be hired as a U.S. “guestworker” for the season. Mt. Olive Pickle Co. has lobbied for guestworker programs, presumably because they help keep down farm labor costs.

3. Guestworkers and other farmworkers are usually required to live in group houses and trailers that often fail to meet basic standards. Many growers claim they cannot afford to upgrade housing.

4. During the season, the amount of work and pay for farmworkers vary greatly, depending on rainfall and crop growth. Workers often go weeks with little work and pay, especially before and after harvests.

5. In July, farmworkers often harvest 10-12 hours a day in 90-degree heat. Farmworkers have no overtime protections, and bosses are not required to offer breaks.

6. Inspectors report the most frequent violations in the fields are failure to provide portable bathrooms and hand washing supplies — leading to health risks for workers and consumers.

7. Mt. Olive representatives visit the that grow its cucumbers to ensure that they use the company’s favored agricultural practices — but disclaim responsibility for working conditions.

8. Most farmworkers are paid at a “piece rate” of about 70 cents per 5/8 bushel (5 gallon) bucket of cucumbers. Depending on the price the grower receives from the grading station, an average worker might earn $6.00 an hour on a good day. The grading station price is largely dependent on the amount Mt. Olive is willing to pay.

9. Mt. Olive pickles the cucumbers in huge vats at its plant and the pickles eventually make their way to supermarket shelves.

10. The bulk of profits from the $17 million N.C. cucumber crop are kept by processors like Mt. Olive. Farmworkers receive so little that the estimated cost of paying every farmworker 50% higher wages would run each consumer less than $4 a year.

11. Mt. Olive Pickle Co. is the 2nd largest pickle company in the country, with about 70% of the market in North Carolina, Virginia and South Carolina. Each consumer who purchases a jar of $2.29 Mt. Olive Pickles indirectly sanctions Mt. Olive’s practices.

Baldemar Velasquez: Healing an Industry

By Sandy Smith-Nonini

The kick-off of FLOC’s 1998 organizing season was a Prayer Warrior’s Vigil, which found Baldemar Velasquez, the union’s president, praying over the pickle vats of the Mt. Olive Pickle Co. It’s not the kind of protest action you’ll find many labor leaders engaged in. But no one has ever called Velasquez a typical labor leader.

The winner of a MacArthur Genius Award for his innovative leadership of FLOC’s 10-year struggle against the Campbell Soup Co. in the Midwest, Velasquez has in recent years found himself studying scripture as well as labor strategies. He is now an ordained minister, and sees no conflict in the two roles.

A recent FLOC planning meeting found the charismatic Velasquez declaring a verse from Corinthians, “The spirit is the Lord, and where the spirit is there is liberty. But the prevailing spirit here in North Carolina is the spirit of bondage left over from slavery. We have to break the spirit of slavery in this state!”

It was the process of the struggle itself, and working with Christian supporters of FLOC, that he credits for developing his spiritual side. After many years regarding churches as “an anglo trick,” Velasquez said, “I began looking at things from a different perspective. I used to take advantage of every incident we came across to point up exploitation. But that doesn’t always lead to the solution of problems. Now I see that FLOC is in the business of reconciling repressive relationships.

“The agricultural industry can be compared to a dysfunctional family. You have to get the garbage on the table, and separate the members in order to get them together again. Fifteen years ago there were some farmers there who would set their dogs on me. Now I go and sit in their kitchens to resolve issues.”

FLOC’s organizing strategies also contrast with the approach most people associate with organized labor. “Other unions do a campaign and whether they win or lose, they leave afterwards,” explained Velasquez. “What I’ve been telling the AFL-CIO is that if you want to organize workers in the South, you have to make a permanent commitment to the community.”

FLOC’s strategy in the Midwest was to make Campbells’ labor practices a moral issue with the public. That strategy hurt Campbell’s national reputation, and is widely credited with bringing the company to the bargaining table.

But to Velasquez, the labor contract itself is just the beginning of the process. He says, “The development of the union is more important than the union. The union is not the goal; it’s a vehicle to build community. It’s not about winning or losing; when a community is developed, victories will come.”

The FLOC campaign is counting on a similar strategy of a long-term struggle that looks to the wider community for moral support of farmworkers’ rights in North Carolina. At a recent consultation on a boycott of the Mt. Olive Pickle Co., Velasquez described the struggle in moral terms.

“What the N.C. agricultural industry is doing with these workers doesn’t square with scripture,” he said. “We’re looking to the churches to support this struggle.”

Tags

Sandy Smith-Nonini

Sandy Smith-Nonini is an adjunct assistant professor of medical anthropology at the University of North Carolina Chapel-Hill and a former investigative reporter for Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South.