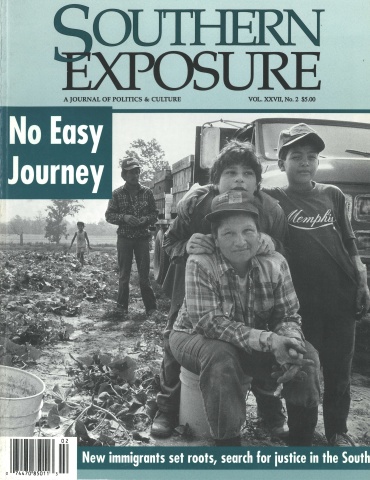

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

On Sundays we take Mama for her drive. Always the same drive. It helps relax her. Cools her out. Instead of fidgeting around the kitchen, which she no longer understands, or trying to work the remote, which she will never understand, she can “feature herself” (as country still like to say) riding in a wide Oldsmobile back seat while the world slides effortlessly by on the other side of the glass. Here it comes, there it goes, now it’s gone. Not quite real, and no commercials either. Nothing to get anxious or confused about.

Emma and I ride up front.

“Your mother thinks the commercials come out of the remote control,” Emma said yesterday, finding me in the basement sorting my father’s tools, for the eleventh time. “She’s upstairs shaking it over the trash can as if it had bugs or water in it.”

It is an uncommon relief, these days, to hear Emma laugh. Laughs are scarce in this little town. Hers especially.

The truth is, I’ve been worried about her lately. Emma. She’s the type who never lets you know something is wrong until it’s too late, so I watch for signs. “Winston, can we talk?” she said last night, Saturday night, while we were getting dressed to go to bed. We sleep in pajams because Mama is up and down all night.

“Talk?”

“Winston, I really don’t know if can stand this any longer.”

“Stand what any longer?”

“We have to get on with our lives.”

“Get on with our lives?”

“And please, please, please stop repeating everything I say. Your mother’s not getting any worse and she’s not getting any better. I don’t know how long I can stand being stuck in Virginia being a geriatric social worker.”

“We have always lived in Virginia.”

“Not this Virginia.”

From downstairs came a roar like water or wind. Mama had hit the wrong button on the remote again. Then came applause, then shots, then laughter. She gets it working again by punching all the button at random. Not her laughter. TV is serious business for Mama. Every night she surfs through thirty-nine cable channels, never stopping on one, as if she’s looking through a big house for something she lost or somebody who’s not there. Opening and then closing every door, but never going in any of the rooms.

“Not this Virginia,” Emma says again, shaking her head. Emma was the Executive Director of the Community Arts Museum in Arlington, until it was de-funded in August. That’s the reason we were both able to come to Kingston when Mama started to lose it. Had her stroke, or rather strokes, a series of small strokes, the doctor tells me. Our kids are grown, the youngest in college. That’s another reason.

“Let’s go for a drive,” I suggest the next morning, Sunday morning, as I always do. “Your Sunday drive, Mama.” I guess if you say so, Winston.”

Mama named me after Winston Churchill, the first international personality to capture anyone’s attention around here. First and last. She dresses herself pretty well, though it can take hours, or seem to. She sits in front of her mirror in her tiny dark room, combing her hair, once her pride and joy. I guess it still is, even white as snow. Eventually she will emerge into the daylight, blinking, powdered and combed but with her slacks on backward, or one sock on and one sock off, literally. She gets agitated and forgets what she is doing. She hasn’t been to church since my father died.

Today’s not so bad. A white blouse and pearls and shoes that match. I lead her into the kitchen where Emma is eating yogurt, from the carton, with a pointy grapefruit spoon. Serrated. “There is sure a lot of this lately,” Mama says when I piece of toast on a plate in front of her.

“A lot of what, Mama?”

“What this is.”

“If you don’t want toast, we can get a sausage biscuit at McDonald’s, Mother Worley,” Emma says.

“I surely do like those ham biscuits.”

“They don’t have them at McDonald’s, Mother Worley.”

“They have them at that other place, Winston.”

“The Sonic, Mama. But they always have such a long line. And it’s all the way on the other side of town. Remember how we always get sausage biscuits instead?”

“You like those McDonald’s sausage biscuits, Mother Worley.”

“I guess if you say so.”

“I surely do say so, Mother Worley. Surely do.”

Emma can be cruel. She talks without looking up. She is reading the paper avidly, you might even say desperately. We got two Washington Posts in Arlington so we could both read them at the same time. Emma calls this paper the Roanoke We-Don’t-Want-To-Know, and I don’t read anything at all. Sometimes I think we are under water. It’s like I returned to my childhood home and it was a pond, and Emma was there too, both of us paddling in circles under the green water.

My father died a year and a month ago last month. I’ve been on compassionate or family leave (we’re still negotiating this, since the effect on my benefits differs) from Urban Affairs for almost four months, since Mother started losing it. My being here helped a little at first, but in the long run we have to do something.

Mama’s standing by the front door, already ready to go.

“Mother Worley, you won’t need to wear that sweater.”

“Well I don’t know.”

“Mother Worley, let’s put that sweater away.”

“I think there’ll be snow in the mountains.”

“Here, Mama, we’ll carry it with us, just in case.”

I carry the sweater on one arm and Mama takes the other, out the door, across the lawn, to the back seat of the Olds. There’s no snow of course, on the mountains or anywhere else. It’s October and this is Virginia, not fucking Norway. From the end of our street you can see the long ridge almost in Kentucky that was stripped off by the coal companies the year I left for college. When I came home that first Christmas it looked like Colorado, if you squinted. I thought it was a great improvement. Funny how taking the trees off a mountain can make it look bigger.

The mountains in the other direction, toward Tennessee, are long and low and green. There’s no coal on Bays Mountain.

Emma gets in the driver’s seat. Mama sits in the back, on the right against the door, and stretches her sweater over her lap.

“Lots of people goin to church today, I reckon,” Mama says as we drive past all three, the Baptist, the Methodist and the Cumberland Presbyterian, all on Main Street. They are all on the same side of the street, in a row.

“We heard from Bob last night,” I say as Emma pulls into the drive-in window line at McDonald’s.

“Our son Bob, Mother Worley,” Emma says. “Your grandson. He’s in Alaska for the clean-up. He called.”

“Well, I reckon so,” Mama says.

“I reckon that’s right, Mother Worley,” Emma says.

She can be cruel all she wants because Mama doesn’t notice. Mama has enough trouble just thinking of things to say. The line is slow. Hardly anybody’s inside McDonald’s. Everybody’s in the drive-in window line. Car truck car truck car. Pencil-colored Japanese cars and trucks. When I was growing up nobody except farmers drove a truck on Sunday. Now nobody farms but everybody drives a truck.

There was no McDonald’s then, either. There was the Sonic, on the other side of town, but it was for Saturday night. We were all teenagers.

“Lots of people at this church,” Mama says.

“Not a church, Mother Worley.”

“This is not a church, Mama. This is a drive-in.”

“Well, I reckon there’ll be snow on the mountains.” Mama stretches her sweater over her knees. I can tell be the way she’s pulling at it, she’s getting agitated again.

The girl in the window gives us three sausage biscuits and two coffees in a sack. I hand Mama her biscuit wrapped in greasy paper, and a napkin.

“I don’t think this is right, Winston. I don’t think this is a ham biscuit.”

“It’s a good McDonald’s sausage biscuit,” I tell her. “It’s your Sunday drive sausage biscuit, Mama. You should see the line at the Sonic. There’s no way.”

Emma sighs, gets a wheel pulling out.

“Is that my coffee you have there?”

“No, Mama.” She always wants coffee but it makes her want to pee, and it’s impossible to find a bathroom in the country. “I didn’t think you wanted coffee, Mama.”

“I always want coffee, Winston.”

“Let’s take our drive out into the country, Mother Worley. Out the Hat Creek Road. Good old Hat Creek, I reckon. I surely do declare.”

I tear a wedge out of a coffee lid so Emma can sip it like a truck driver, the way she likes. We take the same drive every Sunday. Down Main Street through the deserted center of town, past the Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches again, out the Briston Highway, past the Glenn Funeral Home. Past the Cumberland Conductor plant and Bewley Chevrolet-Subaru. Past the Family Dollar Store and the Sonic and the Highway Gospel Tabernacle.

There’s no line at the Sonic (never is), but Emma drives on past without Mama noticing, we hope. Her sausage biscuit is rewrapped in its greasy paper on her lap, untouched.

“Look how the leaves are getting pretty,” I say, but if Mama notices she doesn’t say anything. Actually, they’ve hardly started to turn. The old Bristol Highway leads south across the valley and then east along the foot of Bays Mountain. We’re in the country now. It used to be that Mama had something to say about every house we passed, once we were heading for Hat Creak: “There is where Josh Billings lived. He had a peacock that screamed. There is Madelaine Fussel’s house. It was the nicest house. Her father built every stick. She was stuck-up. Her little brother drownded in a pond.” And so forth. Now she has nothing to say. She stares at the window glass. She unwraps her biscuit and wraps it back up. She stretches her sweater over her knees. We pass the old consolidated school. The lot is filled with yellow buses.

Yellow is such a fall color, just like leaves. I started at this school, before we moved to town. “Look at all the yellow buses, Mama,” I say. It dawns on me that it’s exactly the kind of thing she used to say to me.

Emma follows the same route every Sunday, like a bus driver, out to Hat Creek and back. Past the school, then right at the old auction house on Cedar Hollow Road, then down the hill to Willard’s store, then left on Hat Creek Road. The familiar scenery relaxes Mama, even if it no longer makes her talk. She eases up on pulling at her sweater. She even look across and out the left window once or twice, on the other side of the car.

“Are you comfortable, Mama? Want me to roll your window down?”

She rolls her window down herself. It’s electric.

But Emma doesn’t run at Willard’s store. Instead of going left on Hat Creek Road, she goes straight on Cedar Hollow Road toward Bay’s Mountain. Mama rolls her window back up.

“Just going a slightly different way,” Emma says. “Don’t let it bother you, Mother Worley. Win, don’t you look so surprised. You two are two of a kind. I looked on the map the other day. We’re going the same place we always go. This road leads around the end of the mountain and comes into Hat Creek from the other way. That’s all. Don’t you want to see a little something new?”

I guess I’m game if it’s on the map. “Sure.”

“I don’t like this road,” Mama says, starting to stretch her sweater again. “This is the wrong road.”

“Mama, relax and let’s enjoy the ride,” I say.

“There’s no wrong road, Mother Worley. There are just different right roads. Don’t you want to see some different sights? Different scenery? Why, look at that pretty house over there.”

“We better go back and go the right way. This doesn’t look right to me.”

“No,” Emma says.

The road winds over a low ridge, through trees. Then we come out in another narrow valley just like the one we just left paralleling it. The fields and the farms are the same. The new cars, the old barns. We cross a narrow concrete bridge without slowing down.

“I don’t like this. Those sheep are going to drown.”

There are, of course, no sheep. Just Mama’s anxiety. Was it the stones in the creek, or the light on the water, or some ghost from the past that she saw?

“What a pretty little valley,” Emma says. She’s not being sarcastic for once. It is a pretty little valley. It looks exactly the same as the one on the other side of the mountain. Maybe a little steeper, a little narrower. Or maybe just less familiar.

“I don’t think we’re going the right way. I don’t think I like this road.” Mama is rubbing at the window glass with the side of her hand as if she imagines she can straighten out what she sees through it.

“Sure you do, Mama,” I say. “Wouldn’t this be what they used to call Cedar Creek community? Didn’t you tell me Auntie Kate had a boyfriend in Cedar Creek?”

Auntie Kate was Mama’s oldest sister who died almost twenty years ago.

“I don’t recollect any Cedar Creek. You told me we were just going to get a ham biscuit.”

“I never said that. As a matter of fact, I said we weren’t.”

“You saw the line at that place, Mother Worley. Just relax and enjoy your Sunday ride.”

“The Sonic. I don’t think there was hardly no line.”

“She’s already forgotten we’re taking our drive to Hat Creek, Win,” Emma says, dropping her voice, as if that keeps Mama from listening. “Let her fret a little. Then she’ll be happy as a clam when we get to Hat Creek and she sees we’re right there where we always go. Or is it happy as a pig in shit?” She raises her voice back to what she considers normal. “Happy as a cow in clover, right, Mother Worley?”

“I think you gave me the wrong biscuit, Winston.”

“Wrap it back up, Mama, and we’ll save it for later. There’s the Cedar Creek Holiness Church. Must be closed. Didn’t some friend of Aunt Maddy go to Cedar Creek Holiness Church?” There are no cars in the lot.

“We never knew any Holiness.”

“Sure you did. Daddy’s sister Louise married a Holiness preacher, remember? The one who lived in Kentucky.”

“I think they are all dead now.”

“But he was a Holiness!”

“Quit bickering and look at the pretty scenery, you two,” Emma says. She takes all the curves at exactly the same speed, like an amusement ride. My father’s Olds purrs right along. 77,000 miles, and almost twenty years old. 77,365.09 to be exact. We haven’t seen another car since Emma went straight at Willard’s Store.

“We never knew any Holiness, Winston.” Now Mama’s sulking. I can tell by the way she stretches the sweater over her lap. “I don’t like this road. It’s just not right.”

“What’s wrong about it, Mama?” I actually want to know; I am curious. What does she see that looks so wrong? All these little mountain valleys are the same. You could switch the houses, the farms, even the people around, and nobody would ever know the difference. What’s why I never came back after college. Nobody ever does.

Yet here I am. And Mama won’t say. We pass another church. We pass our first car, or rather truck. A red Mazda.

“They think they’re so smart,” Mama says.

“Who, Mother Worley?”

“Those girls. Those dancing girls.”

“That’s right, Mama. Just relax and enjoy your Sunday ride.”

“They have all the fun, I guess. They’re so smart, they think they understand everything.”

“Who, Mother Worley?”

“Those girls.”

The road dead ends after another narrow bridge, and Emma turns left. “Are you sure this is the right way?” I ask. “Trust me.”

“I think this is a bad road,” Mama says, agitated again. “This is not right.” She rubs the window and then turns away from it. She won’t look out her window. She stretches her sweater so hard it changes color from mauve to pink.

Emma and I ignore her. We are coming down a long hill toward Hat Creek community now. It’s too small to be called a town. Mama doesn’t recognize it because we are driving in from the wrong side. Let her fret a little; it will be a nice surprise when it dawns on her where she is.

Hat Creek is nothing but five or six houses and two stores, one of them closed down for good. Two kids on bikes are making lazy circles around the concrete islands where the gas pumps used to be. I wave (like country people still do) and I am surprised when the boy gives me the finger as we pass. The girl just stares.

“Did you see that?” Emma says.

Houcherd’s store, the open store, is also closed. A sign on the door says DEATH IN THE FAMILY. Emma has enough sense not to slow down, even though I doubt Mama would have noticed. She doesn’t read sign anymore, and the Houcherds were always considered beneath our notice anyway.

The Hat Creek Methodist Church stands alone on the hillside, as pretty as a page torn from a magazine. Leaves are beginning to scatter across the graveyard.

“What did I tell you. Where are we now, Mama?”

“No.”

“Does that mean you don’t know where you are?”

“No.” She looks angry.

“Look over there. There’s the chimney where Aunt Ida’s house was. You told me about the goldfish pond. Remember how you used to tell me how they used to scare you?”

“Are they going to whip him?”

“Whip him?”

“Whip who, Mother Worley?”

“That boy — you know, that boy — I can’t say his name right now, anymore. Winston, you think of it.”

“You think of it, Mama.”

“Well, I can’t think of it. I don’t like this road.”

“Sure you do! This is Hat Creek Road, we’re just driving on it in the wrong direction from usual. Recognize that house? No, on the other side. Over there.”

It’s the old home place, where Mama lived until she was twenty-five. She was the last one to get married. Now she is the last to die. She doesn’t recognize the house because it’s on the left instead of the right. That’s the way old people get.

“Look out the other window, Mama. On the other side.” Emma, who has the master controls, rolls the left rear window down. “Where are we, Mother Worley? Do you know where you are?”

“Damn this shit.”

“What?” Emma, shocked, grins at me.

Mama is leaning across the seat, pushing the button, rolling the left window up. “I don’t want to go in that house,” she says. “There’s nobody in that house. Damn this shit.”

Now she has rolled her right window down. She is tearing little pieces out of the sausage biscuit and throwing them out.

“What did you say, Mother Worley?”

“I said they are all dead. You children think you are so smart. Damn this shit. All I wanted was a ham biscuit and now they are all dead.”

Emma pulls in the driveway. Somebody’s living in the house. I can see a curtain move. Somebody’s coming out on the porch to see what we want.

“I said they are all dead,” Mama says.

“I think we better head back to town,” I say. “Mama, roll your window up. Emma, just back out and turn around, okay?”

Tags

Terry Bisson

Terry Bisson was born in Owensboro, Kentucky, and is the author of five novels, most recently the acclaimed Pirates of the Universe. His short stories appear regularly in Playboy, Asimov’s, SF Age and Fantasy & Science Fiction, and his 1990 short story collection Bears Discover Fire was a Hugo Award winner. (1999)