Newcomers in Numbers

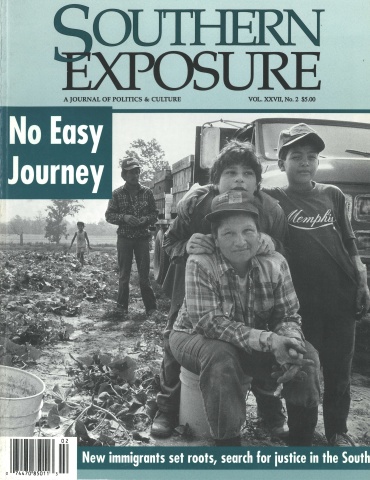

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

The South has been growing rapidly over the last three decades — and immigration from other countries is a leading cause of this explosive growth. Immigration from abroad represents over 20% of the population growth over the last eight years in Florida, Texas, Maryland, and Virginia, and over 10% of the growth in Louisiana, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. Overall, 17% of the growth in the region over the last eight years can be attributed to international immigration.

Who are these immigrants, and what type of work has brought them here? The composition of the foreign-born population has changed rapidly over the last three decades.

Historically, immigration policy in the United States effectively limited the number of immigrants from “undesirable” groups, generally persons with less education and darker skin. The result was a foreign-born population largely composed of aging white Europeans.

Recent legislative changes and increases in the volume of non-legal immigration have changed this pattern. Between 1970 and 1990, the percent of the foreign-born population in the U.S. South from Europe During that same time, declined from 42% to 17%. The corresponding percent for Asians increased from 8% to 19% and the corresponding percent for North and Central Americans (primarily Mexicans and other Central Americans) increased from 42% to 51%. The “Hispanic” ethnic group in the U.S. South rose from eight percent of the population in 1990 to 10 percent in 1997 alone. Over the same time period, Asians increased from 1.3% to 1.8% of the population.

Seven percent of employed immigrants from North and Central America counted in the Current Population Survey work in farming or fishing occupations — although, this group is the most likely to be undercounted, so that’s a low estimate. The largest percentages of workers from North and Central America are employed in blue-collar manufacturing and laborer positions (41%) and service occupations (22%). By comparison, only 27% of native workers are employed in blue-collar occupations and 13% are employed in service occupations.

It is an understatement to say that counting immigrants is an inexact science. Statistics from the government come from three primary sources, each with its own shortcomings. The first — the decennial census — attempts to count every person living in the United States on a particular day every ten years, including the country’s foreign-born population. The second source of data, the Current Population Survey (CPS), is also administered by the Census Bureau, which began asking about place of birth, citizenship and length of residence in 1994. Finally, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) collects data on applications for legal immigration, and estimates “illegal” immigration from a variety of sources. There are also various private organizations and researchers who estimate immigration (primarily “illegal”) using surveys, interviews, information from employers, and apprehensions on the U.S. borders.

The decennial census and the Current Population Survey are still the best sources and are used in the charts below. However, there are shortcomings. Each is a household-based survey, and those immigrants who are living in temporary or hard-to-find homes, such as agricultural migrant camps, are not likely to be counted. This, along with the fact that “illegal” immigrant groups do not want contact with government organizations, guarantees that North, Central and South Americans will be undercounted.

On top of that, immigrants with low levels of education are undercounted because of their inability to fill out forms, and census-takers face a difficulty in contacting people without traditional “9 to 5” jobs. All of which is to say that estimates of immigrant populations are only show the lower limits of who is really here.