Foreigner, Go Home!

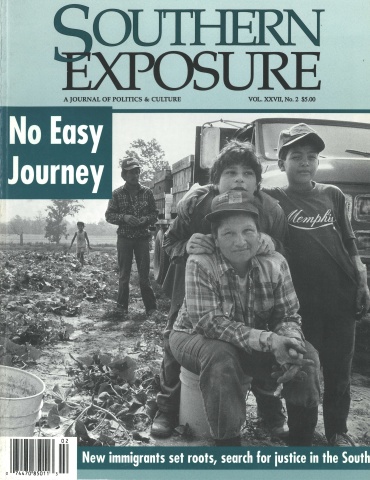

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

“Lydia” is an American whose roots in western North Carolina run deep. She owns a home in Asheville and works full time at a mid-management job in human resources. A devout Christian, she’s also been active in missionary work for years, particularly in Mexico and South America.

About two years ago, Lydia met “Jorge,” who had immigrated undocumented from Mexico in 1994 because he was unable to find work there (the unemployment rate in Mexico is about 50 percent, and it had soared to almost 75 percent in Jorge’s small village). The two have recently become engaged, and both asked that their real names not be used.

After a short stint working in the Texas watermelon fields, Jorge is now working full time in western North Carolina in construction, “paying taxes and supporting this country,” as Lydia puts it, “but we’re trying to buy things together, as a couple — and his income, of course, can’t even count on our credit applications,” because he doesn’t have a green card.

“He can’t write a check, or do the things we take for granted every day,” she continues. “He can’t walk into a bank and deposit his money.”

And recent, sweeping changes in immigration law — most notably the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) — have made it difficult or impossible for Jorge ever to become a legal resident.

“We’re going to get married, no matter what,” Lydia declares. “But I’ll live with the fear every day that [the Immigration and Naturalization Service] will show up and take my husband away.”

Jose Concepcion Pina Patino is a legal permanent resident here, along with his wife, Maria Theresa, and their five youngest children (who range in age from 9 to 21). Jose’s workday at Holly Brooks Dairy Farm in Fletcher starts at 7 a.m. and usually doesn’t end until after dark.

He immediately apologizes for his poor English skills, pointing out that those long work hours leave precious little time for taking language classes. “I feed and milk 300 cows daily, am responsible for planting and harvesting the corn and other crops, plus keeping all the barns clean,” he relates.

The family lives in a tidy but sparsely furnished frame house on the dairy-farm grounds. Rigoberto, the couple’s 21-year-old son, is confined to a wheelchair: Lacking even the simplest motor functions, he requires around-the-clock care, most of which his mother provides.

But that effectively eliminates whatever chance she might have of obtaining work outside the home, making it even tougher for the couple to meet new federal income requirements that would allow their two other children, Juan Carlos and Marisela, both now in their early 20s, to lawfully immigrate. Ironically, the whole family’s financial situation might significantly improve if Juan Carlos and Marisela were working here, and helping care for Rigoberto. This is especially true since under IIRIRA, Rigoberto is barred from receiving disability or other benefits — even though he’s a legal resident.

“I hope that, somehow, someone can help my son,” says Maria Theresa quietly, adding, “If not, we’ll just keep dealing with it here.”

Closing the Door on Immigrants

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” These words emblazoned on the Statue of Liberty have beckoned countless immigrants to a fresh start in the so-called land of plenty — a fresh start in a nation of immigrants (see “This Land is Whose Land?” p. 30).

Over the past two decades, however, U.S. immigration law has become more and more restrictive — and confusing. Asheville immigration attorney Jane Oakes says the laws now change so fast that even lawyers find it impossible to keep up. And increasingly, immigrants in western North Carolina, as they are all over the South, are finding themselves caught in a tightening net of legal restrictions.

The law’s changes, according to the legislation’s summary, were “needed to address the high current levels of illegal immigration; the abuse of humanitarian provisions such as asylum and parole; and the substantial burden imposed on the taxpayers of this country as the result of aliens’ use of welfare and other government benefits.”

And there’s no lack of voices in this country calling for even stricter immigration limits, especially in places like California, where almost half of America’s estimated five million “illegal” immigrants now live. “In L. A., the [illegal-immigrant] situation is approaching civil war,” Glenn Spencer, chairman of the antiimmigrant watchdog group Voices of Citizens United, told Los Angeles Times reporter Maria Puente last year.

But in smaller, rural areas — like western North Carolina’s Henderson County — immigrants, both documented and undocumented, do the lion’s share of the agricultural work that is a mainstay of the local economy. In many instances, employers say they depend on that immigrant labor to do work that U.S. citizens don’t want to do.

Yet, in the wake of IIRIRA, these immigrants face the same legal hurdles as their big-city counterparts, in their quest to obtain “legal permanent resident” status — the right to live and work in the United States indefinitely, symbolized by the so-called “green card” — which hasn’t been green in years.

Raising the Bar

One of the biggest hurdles facing prospective immigrants who are trying — as attorney Oakes puts it — “to do things by the book,” is Section 203 of IIRIRA: the Affidavit of Support provision. It says that any immigrant not sponsored by an employer must have a financial sponsor — one who earns 125 percent of the federal poverty income guidelines — to enter this country.

The sponsor must sign an eight-page, binding contract with the U.S. government assuming financial responsibility for the immigrant. The affidavit is legally enforceable against the sponsor for five years or until the immigrant becomes a citizen.

“If the immigrant ended up needing to receive public assistance, the government could sue the sponsor for the money,” explains Hispanic/Latino Services Coordinator Toerin Leppink of Catholic Social Services. “So it’s pretty much impossible to find a sponsor other than a family member.”

And while an income of 25 percent above the poverty level may not sound like much, for immigrant farm workers, this requirement can be highly prohibitive.

“What I have now is family after family that come in who are petitioning for, say, two of their children to come over, and they simply don’t make enough money,” says Leppink.

That’s precisely the Patinos’ dilemma. The couple’s two oldest children have been waiting to immigrate since 1991. In the meantime, however, they’ve both turned 21 — and been moved into another INS category, which requires the Patinos to meet the Affidavit of Support rule.

Making things even tougher for immigrants like the Patinos is the fact that, despite the lower wages in western N.C., they’re being asked to meet the same income guidelines as a person living in L.A. or New York City. In order to sponsor their two oldest children, for example, the Patinos, a family of nine, would have to prove an annual income of $37,062.

“The Affidavit of Support rules are not based on reality,” charges attorney Josh Bernstein of the National Immigration Law Center, a Washington, D.C.-based immigrant-advocacy organization. “There are situations where you have elderly, financially struggling parents who want to bring over their healthy, working, adult children. In that case, the parent who’s here is going to benefit, and all of society will benefit.”

Jose Patino, for one, sees little hope for reuniting his family. “I have stable work and a very small amount of money in the bank,” he says. “But I’ll never be able to bring in enough money to bring my children over.”

The Pit and the Pendulum

Shifting political winds in America — and the sometimes-contradictory immigration laws they spawn — can create a bewildering maze of restrictions for immigrants in quest of a green card.

Conflicts between IIRIRA and prior legislation (which may have been in force when these immigrants arrived) have left many immigrants between a rock and a hard place.

For example, Section 245(i) of the 1994 Immigration and Nationality Act allowed immigrants who had entered the country without documentation — but who met certain specified conditions — to pay a $1,000 fine and achieve legal status here, without having to return to their country of origin. After a hard-fought battle in Congress, and several “stays of execution,” anti-immigration forces succeeded in killing Section 245(i), effective Jan. 14, 1998.

But under IIRIRA, any undocumented alien who was in the United States for six months or more after April 1, 1997 and leaves the country for any reason will be barred from re-entering the U.S. for three years. If they were here illegally for a year after the April 1 cutoff and then left the country, they would be barred for 10 years.

What’s more, undocumented immigrants who did not leave before April 1, 1998 can no longer achieve legal status by marrying a U.S. citizen, or getting sponsored by a family member, as had been allowed under Section 245(i). And while the battle over that provision raged in Congress, many immigrants were left wondering what to do.

“There was this huge dilemma,” says Leppink. “Do you leave the country before the first six months are up and [try to] adjust status at the border — or risk staying in the country, in hopes that [provision 245(i)] will be further extended and you pay your $1,000? Nobody knew what was going to happen.”

When Jorge initially entered this country, his brother was already here, in the process of becoming a legal resident. Jorge assumed that he could eventually either apply for legal residency, sponsored by his brother, or pay the $1,000 fine and get a green card.

But as the expiration date of 245(i) approached, Jorge — who was by then engaged to Lydia — had three choices: He could leave immediately and apply for legal status from Mexico; leave before the six-month deadline and be barred from coming back for three years; or stay, in hopes that the embattled provision would be extended indefinitely. Jorge chose to stay — thereby running the risk of being barred from this country for 10 years.

Jorge and Lydia’s story, says Oakes, is all too familiar.

“The [repeal of 245(i)] is supposedly discouraging people from being here illegally,” she points out, “but, in fact, the [new] legislation is actually encouraging people to stay illegally, rather than leave and be barred for 10 years — especially those who now have families, marriages, serious relationships.

“Lawmakers are saying, ‘We’re tough on people who are here illegally,’ but it’s not working,” Oakes adds.

Supporters of more stringent immigration restrictions think IIRIRA hasn’t gone far enough. Martin and FAIR feel the way to handle illegal immigration is simple and obvious: Deny all jobs to illegal immigrants.

That may be easier said than done, of course — because many of these immigrants end up doing work that no one else wants, for wages most Americans wouldn’t work for.

And that’s just not fair, argues Russell Hilliard, pastor of the West Asheville Hispanic Baptist Mission. Hilliard, a former missionary in Spain, is an active advocate for western North Carolina immigrants — attending INS hearings, teaching English classes, and generally acting as both friend and political ally to documented and undocumented immigrants alike.

“It feels like a new serfdom is being created in America,” says Hilliard. “We want these people to harvest our crops and clean our toilets and do all the dirty work, pay them almost nothing to do it, and not [give them the chance to] receive any benefits or ultimately have the possibility of becoming U.S. citizens.

“I place the blame for most of this on a world that’s supposedly moving toward a global economy,” Hilliard continues, “and on a few of our Congressional leaders, who have reverted to a colonialism of the rankest caliber in regard to immigration policies.”

If there has been one benefit of the Act, says Josh Bernstein of the National Immigration Law Center, it’s that it has helped forge a potent political alliance. “The bill is so horrible, in that it throws all immigrants together and treats people who have been here for years like they’re suddenly suspect that it’s caused immigrants to come together for the first time and sort of recognize their stake in political participation.”

That shift, he says, is “reflected in the huge numbers that have been applying for citizenship in the last couple of years [1.6 million in 1997, up from about 225,000 per year in the ‘80s and early ‘90s]. That’s a direct result of this legislation. It’s pushed people to become citizens, to vote, to get involved.

“Inadvertently, IIRIRA has empowered immigrant communities.”

Let Them Eat Regs

The sweeping Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 contains a whopping 671 sections, with provisions amending everything from land-border inspections to the salaries of immigration judges. One of the law’s more controversial aspects has proved to be its drastic cuts in all forms of public assistance for immigrants — cuts which reinforced the effects of welfare reform.

In the wake of both IIRIRA and welfare reform, most legal permanent residents were denied Medicaid, food stamps and SSI disability benefits — no matter how long they’d been legally working and paying taxes, just like their American-born counterparts. Subsequent legislation restored SSI benefits and Medicaid eligibility to some of the immigrant groups. And last summer, Congress gave states the authority to restore food stamps to most immigrants who had been legal permanent residents for at least five years. To date, though, only about 13 states have done so, and North Carolina is not one of them, though pending legislation may restore benefits to certain immigrant groups.

Most legal immigrants remain barred from receiving any form of federal public assistance for their first five years of legal residency in the United States. And legal permanent residents must accrue 40 quarters of steady employment in America (about 10 years’ worth) before they can qualify for disability benefits.

Ironically, notes attorney Jane Oakes, most undocumented immigrants are paying taxes, even though they’re now denied any benefits. Anyone, she says, can readily get a taxpayer ID number from the government.

Proponents of the cuts in public assistance to immigrants argue that a disproportionate number of immigrants end up receiving such benefits at some point during their lifetimes.

But statistics on this issue vary widely. A survey conducted by the Federation for American Immigration Reform (which supports stricter immigration laws) reports that immigrant households are far more likely to use benefit programs than the households of American-born citizens — 47 percent more likely, according to FAIR’S survey. Various other statistics, however — including those compiled by the National Immigration Law Center (a Washington, D.C.-based immigrant-advocacy organization) — show little difference in the two groups’ use of such benefits.

Family Values

Critics also charge that the new laws tear immigrant families apart with arbitrary rules. A case in point is the story of Sergey Ivanchenkov.

On the surface, Sergey’s life in the small, former Soviet republic of Uzbekistan seemed ideal. As chief executive director of the Swedish corporation Molnlycke SCA, he enjoyed a company car and a company-paid apartment, on top of his generous salary. And he had just married his longtime sweetheart, Marina Aziliyevna. That was 1996, when Ivanchenkov was only 25.

But all was not well — not by a long shot.

As Christians in the middle of a Moslem country, he and his new wife feared for their lives, Ivanchenkov says, describing religious persecution in Uzbekistan as “rampant.”

“Gangs went around all the time breaking into homes, killing people, robbing them,” he remembers. “We were unsafe, especially because we lived in a place where these gangs knew people had some money and good possessions.”

Ivanchenkov says he felt he had two choices: stay there and be in constant danger, or come to the America and start over in a country where he felt he’d be safe and have unending career opportunities.

Ivanchenkov, along with his elderly parents, applied for and were granted “parole authority” to come to the U.S. Parole is a temporary status allowing non-citizens to enter the U.S. to escape potentially life-threatening emergencies — such as persecution based on race, religion, nationality or political opinion — or other humanitarian reasons. After three months, parolees are given authorization for temporary employment, and after one year, those who have been granted political asylum may apply for legal permanent residence in America.

Ivanchenkov planned to find work and then bring Marina over, a process he thought would take about a year. In the interim, however, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act kicked in, bringing tough new standards for both parole and asylum.

After completing the necessary paperwork, Ivanchenkov and Marina waited for what they thought would be the inevitable granting of her parole status. Under the new rules, however, Marina didn’t qualify.

As dicey as her situation in Uzbekistan might be, Immigration and Naturalization Service officials say it doesn’t constitute “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public interest,” as required by the new parole guidelines. And another new restriction — requiring victims of religious persecution to have practiced their religion for at least 10 years — further hinders her efforts to gain parole. Though Marina is now a practicing Baptist, like her husband, she wasn’t one 10 years ago — when she was 15 years old.

“I’ve tried every avenue,” says Ivanchenkov, pulling out a folder filled with INS petitions and letters he and others have submitted on Marina’s behalf. “But [the INS has] made a total refusal for her and closed the case.”

One of Ivanchenkov’s few remaining options is staying in America for five years after being granted legal permanent resident status — the time it takes to become an American citizen — and then submitting a spousal petition to bring Marina over. But in his mind, that just isn’t feasible.

“She’s my wife: I’m here, she’s there,” he states simply. “And I only lived with her for less than a year. I don’t see how I can wait that long to see her and live with her again.” (Under parole guidelines, if Ivanchenkov left America to visit Uzbekistan, he would not be allowed to re-enter.)

All is not well for Ivanchenkov on the employment front, either. With a four-year degree in aircraft design and civil aviation, and four years’ experience in business management, one might think he would have some prospects. Yet, despite his impressive resume, Ivanchenkov has been unable to find employment in anything even close to his field.

He now puts in a 72-hour work week — waiting tables and working on an assembly line — trying to make as much money as possible, in case he has to pay what he calls “big money” for immigration attorneys to somehow work a miracle. Ivanchenkov, however, reports that attorneys in at least seven states have already said there’s nothing he can do — short of waiting to become a citizen.

So, despite the dangers, Ivanchenkov says he’ll probably end up going back to Uzbekistan to live with Marina.

“What has surprised me most about all this is that America supposedly stands for family values,” he observes. “Everyone talks about that all the time. But then they won’t allow husbands and wives to be together. That doesn’t seem like family values to me.”

Good Aliens and Bad Aliens

For the past decade, the immigrants’ worst foe has been Bill McCollum, the Republican House Representative from Florida. McCollum has authored a spate of anti-immigrant measures, each one more vicious than the last. Under McCollum’s bills, the INS departed 171,154 people in 1998, topping the previous record of 114,386 set in 1997. In 1999, deportations are averaging an astounding 17,000 per week.

Until now the only immigrant group to escape McCollum’s punitive measures has been Cubans; others have been booted out of the country for such minor infractions as parking violations. Now McCollum is having second thoughts. He recently took to the floor of the House to reflect that the law, which he drafted, may by “too harsh and indiscriminate.”

What prompted this change of heart? McCollum was pleading for leniency from the INS for a young Canadian man, a convicted thief and forger named Robert Broley. When the INS ignored McCollum’s pleas, the congressman drafted a bill that would exempt Broley from the expulsion provisions of the law.

He said this boy’s story was “personally compelling.” Broley’s father just happens to be the treasurer of the Republican party in McCollum’s south Florida district.

From CounterPunch, 3220 N Street NW PMB 346, Washington, DC 20007-2829.

Tags

Marsha Barber

Marsha Barber is a writer based in Asheville, North Carolina. This story was sponsored by the Asheville-based Fund for Investigative Reporting. (1999)