This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

By the time Carmen E. crossed Buford Highway to get to the nearest prenatal clinic, she could barely see well enough to dodge the speeding traffic.

It was last May. Carmen was six-and-a-half months pregnant. She’d suffered skull-splitting headaches and fainting spells, and her legs were badly swollen. She had finally decided she needed medical attention.

When clinic workers at the Clinica del Bebe in Norcross checked her vital signs, Carmen’s blood pressure was so high that she was rushed to the hospital, where doctors immediately performed an emergency C-section. The struggling, premature boy was then whisked away to the neo-natal intensive care unit for close monitoring.

If Carmen had had a prenatal exam even a few weeks earlier, she might never have gotten sick, notes the clinic’s director, and her baby might have gone full term.

But Carmen was doing what, in a roundabout way, now seems to make sense for low-income, undocumented immigrants. Since Congress passed a sweeping welfare-reform package in 1996, expectant mothers in Georgia who are in this country without legal papers haven’t had access to Medicaid coverage for prenatal care. As a result, many such immigrants are postponing exams, skipping appointments or foregoing prenatal care for their entire pregnancies.

Although the health risks of not getting prenatal care are well known, large numbers of undocumented women fear racking up huge medical debts or attracting the attention of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. So they don’t go, and just hope for the best.

Some health officials say they’ve already seen an increase in maternal health problems and premature births in metro Atlanta’s immigrant community. For Georgia residents, that development could spell a costly new public-health concern: Their parents may be undocumented, but the new babies are U.S. citizens and, therefore, entitled to Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for poor people. If undocumented immigrants’ newborns enter the world with grave medical problems, the public expense starts immediately and, depending on their condition, may continue for years or even lifetimes.

An Ounce of Prevention

Given the enormous (and growing) expense of medical care, the taxpayer-borne costs of treating sickly, premature babies may only be a preview of decades of more medical problems — and more public costs. The ironic consequence is that welfare reform — which was envisioned as a cost-cutting measure — may end up actually spurring more public expense.

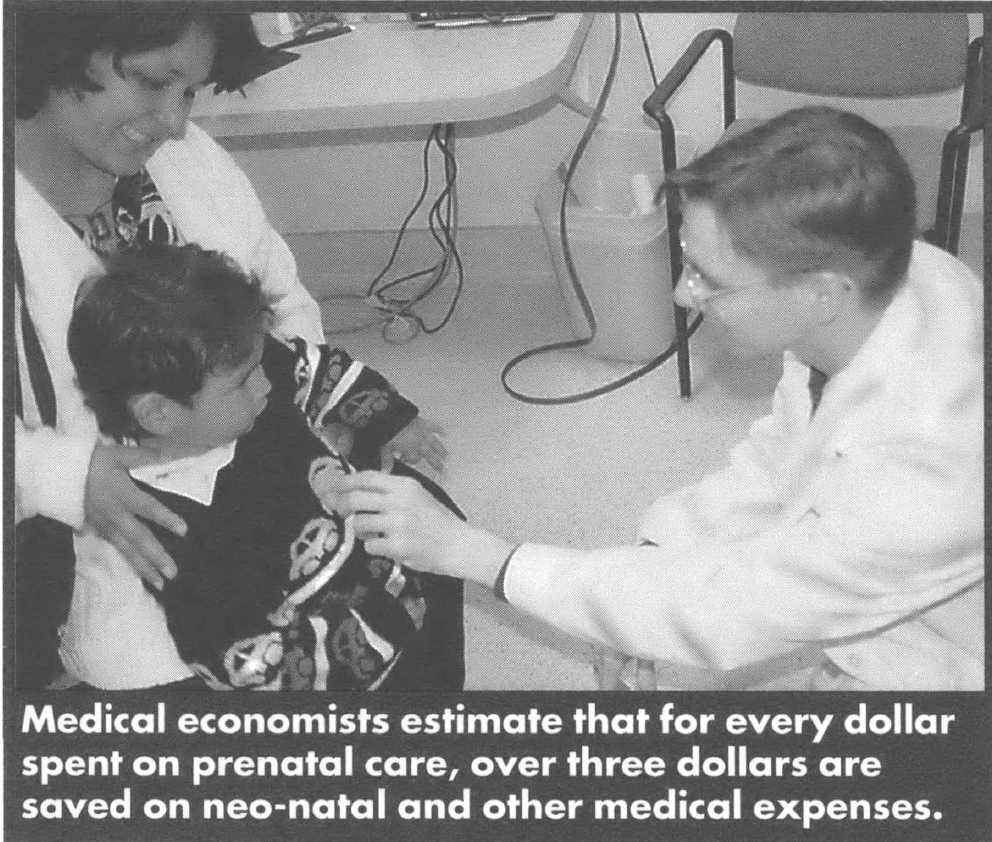

Medical economists at the Institute of Medicine in Washington D.C., estimated in 1985 that for every dollar spent on prenatal care, $3.38 was saved on neo-natal and other medical expenses — a figure most likely to have risen over the last decade and a half.

The issue has emerged at a time when metro Atlanta’s Hispanic population, both with and without documents, has skyrocketed, increasing overall by 78 percent between 1990 and 1996, according to Census Bureau estimates. Immigrants from Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean have streamed into the metro area to dig ditches, clean chickens, wash dishes, and tackle other grunt jobs nobody else wants — the kind of jobs that don’t generally offer benefits packages. In addition to providing for themselves and their families, immigrants often are sending money to the relatives back home.

Carmen’s husband fled his home in El Salvador in 1989 to escape the civil war there. Carmen followed, and the couple and their two children moved to Atlanta last year seeking work. Carmen’s husband found a job working for a glass company five or six days a week. He brings home about $400 a week, with no benefits.

Soon Carmen discovered she was pregnant again. During her two earlier pregnancies, first in El Salvador and then in her home country of Mexico, she’d visited doctors regularly. But here, with no medical benefits available through her husband’s job and limited by her inability to speak English, Carmen didn’t know where to turn for help. “I don’t know anybody here,” she says. “I never went anywhere because of that.”

Sarah Roberts, a health educator working with immigrants at a local Atlanta hospital, says social isolation is a significant hurdle for undocumented women who need prenatal care.

“Atlanta is very different than, say, California or Florida or the border in terms of the support they have,” says Roberts. “The population here is fairly newly arrived and, mostly, the men come to work, and the women come to be with the men. So they don’t have their moms and their grandmothers and their aunts. They are really out there by themselves, and they don’t have good information.”

Carmen had never had serious health problems, and she’d had no complications carrying or giving birth to her two older children. This time, though, at six months along, she started getting sick. In addition to her legs swelling, she began seeing spots and flashing lights. After eight days of such symptoms, she heard a radio spot about Clinica del Bebe, a privately owned clinic for poor, expectant mothers very close to Carmen’s home in Norcross.

“This clinic for me was good because they speak Spanish,” she says. “The first time I came here I had a terrible headache.”

Although she’d felt fine for months, Carmen had developed severe toxemia and gestational diabetes. Among pregnant women, five to seven percent contract toxemia, a type of pregnancy-related high blood pressure. Suffering from both conditions, an expectant mother may feel fine in the early stages. Regular prenatal exams usually catch toxemia and gestational diabetes, which can then be managed until the fetus comes to term. Left untreated, however, the conditions can worsen and result in birth defects, premature deliveries, and sometimes even the death of the mother and the baby.

“Carmen is one of the greatest arguments for prenatal care that exists, because you can be getting sick and you can’t even feel it,” says Tracey Erwin, a health administrator who opened Clinica del Bebe in May to serve the prenatal needs of Hispanic immigrants.

When Carmen arrived at the hospital and was prepped for an emergency C-section, there was no one on hand to explain what was happening in Spanish. In fact, Carmen was at first uncertain whether her baby had even survived.

“He was born. I saw him for just a moment and then he was gone,” she recalls. “For a while I thought he was dead because I didn’t know what was going on.”

After five days in the hospital, Carmen was discharged, but the baby stayed behind, struggling for life in the neo-natal intensive-care unit.

Although Medicaid wouldn’t pay for regular prenatal care for Carmen, it does cover emergency care for undocumented immigrants, and even routine deliveries fall into the “emergency” category. So Carmen’s bills for delivery and hospitalization were sent to the state. Her baby, John Anton was, in turn, fully covered by Medicaid for his hospital stay because he is a U.S. citizen.

It’s not difficult to see how such complicated deliveries and emergency care for premature infants can cost taxpayers far more than prenatal coverage. At Grady Memorial Hospital, for example, the average cost for a single day’s stay in the neo-natal intensive-care unit is $2,000. The standard cost of the full package of all prenatal visits, lab tests and ultrasound at Clinica del Bebe is $1,500.

“The financial aspects of this are crazy,” says Robert Taylor, director of the DeKalb Board of Health’s North DeKalb Health Center, which serves the large immigrant communities in Doraville and Chamblee. “We’re creating medical problems for people that can be lifelong by not allowing their mothers to have prenatal care.”

Election Year Crack-Down

Before President Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, some undocumented pregnant women in Georgia routinely obtained Medicaid coverage throughout their pregnancies by circumventing restrictions through a loophole called Presumptive Eligibility. When applying for Medicaid, women with proof of pregnancy were considered to have immediate need for medical treatment and were issued a Medicaid card on the spot, rather than having to wait weeks for the application to be processed. An undocumented woman’s information would be submitted and eventually her application would be rejected. Then, she’d just go to another Medicaid office and get another card, repeating the cycle of application and rejection until she finally had her baby.

Then came welfare reform. In the heat of an election year, Congress and the president were eager to get tough on “illegal” immigrants.

“Anytime you mention services for undocumented immigrants, it becomes a political battleground,” says Sally Harrell, executive director of the Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia, a non-profit agency dedicated to reducing infant mortality.

To comply with the new laws, the Georgia Department of Medical Assistance started requiring women applying for Presumptive Eligibility to sign a Citizenship Declaration Form. Undocumented women may have been willing to feign ignorance about Medicaid’s qualifying rules, but they were afraid to blatantly lie, especially on a form that included their names and addresses.

The new regulations, though prohibiting the use of federal funds for undocumented health care, include a lot of ambiguities and haven’t yet been fully tested in court. States that already had programs to provide prenatal care for all those in need — regardless of immigration status — continued to offer prenatal care after the new regulations were enacted. Others have found more roundabout ways by channeling dollars to county health programs and private clinics. Unlike a number of other states with large immigrant populations, Georgia has never had a program specifically funding prenatal care for undocumented immigrants. With welfare reform taking effect just as large numbers of undocumented immigrants are coming to the area, the state has been caught unprepared for the consequences of withdrawing benefits.

And little has been done here to fill the prenatal care gap and few voices have emerged from the Latino community willing to speak out on such a political hot potato. In November 1997, a study committee chaired by Sen. Nadine Thomas, D-Atlanta, began looking at the effects of welfare changes on immigrant health services, but benefits for documented immigrants took precedence and further study of the issue was put on hold — at least until after last year’s election cycle. With a new governor and a new Legislature now angling to address their own priorities, the outlook for action on such a potentially explosive, expensive issue is murky.

“Hopefully, we’re going to take a serious look at it,” says Thomas. “It is a problem because women are not going to seek care, and [they] end up with complications.”

Some of the complications already are apparent. Health-care providers, social workers, and public-health officials across metro Atlanta report that they are observing that in greater proportions many undocumented immigrant women are either skipping prenatal appointments, coming in late in pregnancies for their first exams, or going without prenatal care entirely.

“You always have a certain percentage of people who will have premature births; that’s a given,” says Taylor of the North DeKalb Health Center. “But now you’re seeing more. More problems with the actual delivery process and problems with the child.”

He says that there has not been a huge increase in problem cases, but notes that even a small increase translates into enormous expense. “The amount of money it takes to care for one child that has serious problems is huge,” he warns.

The new bills will mostly be sent to the Department of Medical Assistance, Georgia’s Medicaid agency. Despite the potential impact of the issue on agency coffers, Kenya Reid, DMA’s director of public information, reports that no one at Medicaid is presently looking at the economics of withholding prenatal care from undocumented immigrants.

Barriers to Health

The cost of care is not the only concern for the undocumented immigrant community. Tapia of the Latin American Association says, “If they don’t have insurance, in many cases, they believe they won’t be able to afford the services they’re looking for.” As new arrivals, many immigrants have no idea how Atlanta’s intricate health system works. Plus, without English skills they are often unable or intimidated about seeking help.

They also might be reluctant to seek care for fear of entering the radar of the INS. Health professionals insist that immigrants don’t get into trouble with the INS by getting medical attention, but such reassurances mean little to people whose livelihood depends on staying in the country.

“People are concerned about their undocumented status and jeopardizing their family,” Tapia says.

The situation has created a new marketplace for prenatal care and, to some extent, both public and private providers have responded.

“In the last two years we have seen low-cost services and creative solutions spring up,” says Sally Harrell, executive director of Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies.

The availability and rates of the new low-cost providers vary greatly from county to county. For example, the Cobb County Board of Health cut a deal with the Northwest Women’s Center and Cobb Midwives to provide a $520 package of prenatal exams, not including lab work or ultrasound.

Moderately priced, privately owned providers are attempting to fill the gap in other areas.

“I started doing this because there was a huge market out there that could justify the expense of having their own clinic,” says Tracey Erwin, director of Clinica del Bebe. Everyone on staff is bilingual. A van service picks up women without transportation for their appointments. Recently, the clinic added an in-house Medicaid caseworker to help women apply for the emergency coverage they’d need to pay for deliveries.

Since opening its doors last May, Clinica del Bebe has built its practice to nearly 700 patients. Still, the clinic’s price of $1,500 for a full package of exams and tests is a substantial expense for a clientele with typical weekly incomes of $250-$400.

“They come here to work and have a better life for their families,” says Erwin. “They do pay for the services. They find a way to pay, because the health of their babies is very important.”

In Carmen’s case, the contorted rules now governing the illegal-immigrant, prenatal-treatment game twisted the rules of efficiency. The fact that she waited until she was gravely ill allowed Medicaid to cover all medical expenses for her and her baby. Carmen ended up staying five days in the hospital. John Anton was held in the neo-natal intensive care unit for nearly a month. When he was discharged, the hospital sent him home with a heart monitor.

Very quickly this new, young American ran up more than $50,000 in medical expenses. If he had had lingering medical problems, taxpayers might be footing the bill for the rest of his life.

Fortunately for him and his mother, the trials of being born in the United States ended happily. Carmen now beams as she cradles the chubby eight-month-old infant.

“He eats a lot,” she says with a smile.

Tags

Maureen Zent

Maureen Zent is a writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. A version of this story originally appeared in Creative Loafing. (1999)