This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

Fifty years ago Amanda del Carmen Villatoro held a guitar on her lap as she and her family took a bus from El Salvador to California. As my mother and her family settled into California, my father, Ralph McPeek, stood on the bow of his ship. Six weeks had passed since the South Pacific war ended. The young sailor planned to ride a Harley Davidson, like the one he had recently seen sparkling in a magazine, from California back to his home in Tennessee. While waiting on the bike, Ralph got a job a carpet cleaning company.

My mother had just left the carpet company, but one day she returned to visit, and was casually introduced to the young ex-sailor. Though she could speak little with him, she did notice his green eyes that darted timidly her way.

They dated. A week later, Ralph drove a shiny cycle to Amanda’s home in the Mission District. Ralph stood with one foot on Capp Street while he pulled the goggles up and over his leather helmet. He smiled at her, and this time his green eyes did not dart away.

Ralph never learned Spanish. Amanda knew little English. Naturally, they got married.

For their honeymoon, they drove across the nation in 10 days, taking their time, meandering off the beaten path of Route 66. In Tennessee, Ralph drove through Memphis and Nashville in one day. They left 66 behind and took familiar backroads into the eastern hills of the state. “I’m taking you home, honey,” he said over his shoulder.

Amanda gazed at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains that toppled into deep lakes and rivers. As they passed through the green of that summer, into a heat that penetrated the leather of her riding suit, the young girl from the old country believed for a moment that she had crossed the border on the Harley and returned to El Salvador.

“This is home,” she whispered.

It would be, for the next fifty years. Here she would become a citizen and perfect her English, flavoring it with a Salvadoran-Hillbilly accent.

That was the first of nine trips across the country on the same Harley. They finally settled in Tennessee, where they raised my older brother Alan and me. Alan remained in the Tennessee area, adhering more to the Appalachian culture. As an adult I ran back to Central America, as if looking for something my mother had left behind.

My wife Michelle and I lived in Guatemala and Nicaragua for several years. There I found my mother’s Raza — living and working in communities of people who struggle to survive, I became more intimate with that spirit called Latino, which I thankfully call mine.

When we returned to the United States, Michelle and I sought out a Latino community. We thought it would be necessary to move to Texas or Los Angeles. But coming to the Southeast United States was the only trip we had to make. Just as my mother found home here half a century ago, a community of Latins is now finding home in the deep South.

While living in the northern jungles of Guatemala, I remember watching old, large trucks pull into our neighborhood. The driver, many times Mexican, would step out and offer his coyote services to anyone interested. For five hundred dollars a head, you could climb aboard the back of the dusty vehicle. The driver promised to drive you all the way through Mexico and into the United States, where you could escape the poverty, violence, and any other societal aches that kept them from prospering at home.

Many of those people who board coyote trucks in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico never reach their goal of prosperity. There are nightmare stories of individuals left in Arizona deserts to die, their forgotten cadavers littering the border’s edge. Others fling themselves into El Norte and disappear into the large Latino populations in multi-ethnic cities.

Yet many are now giving up the ethnic connections in Los Angeles and Dallas, and moving to Tennessee, Alabama and the Carolinas, searching for jobs and tranquila lives.

The pattern of sowing cultural seeds is a simple one: After the first few arrive, others follow behind. Although the “wave” of immigrants generally begins with individual men who come to work a tomato or tobacco crop, it doesn’t last. Having sacrificed one or more seasons separated from their families, the men bring their wives and children, who may also work beside them in the fields and factories. By the fifth or sixth year, the grandparents are in back of the car. The vehicle can no longer support the family; it’s time to settle. A Latino community is born.

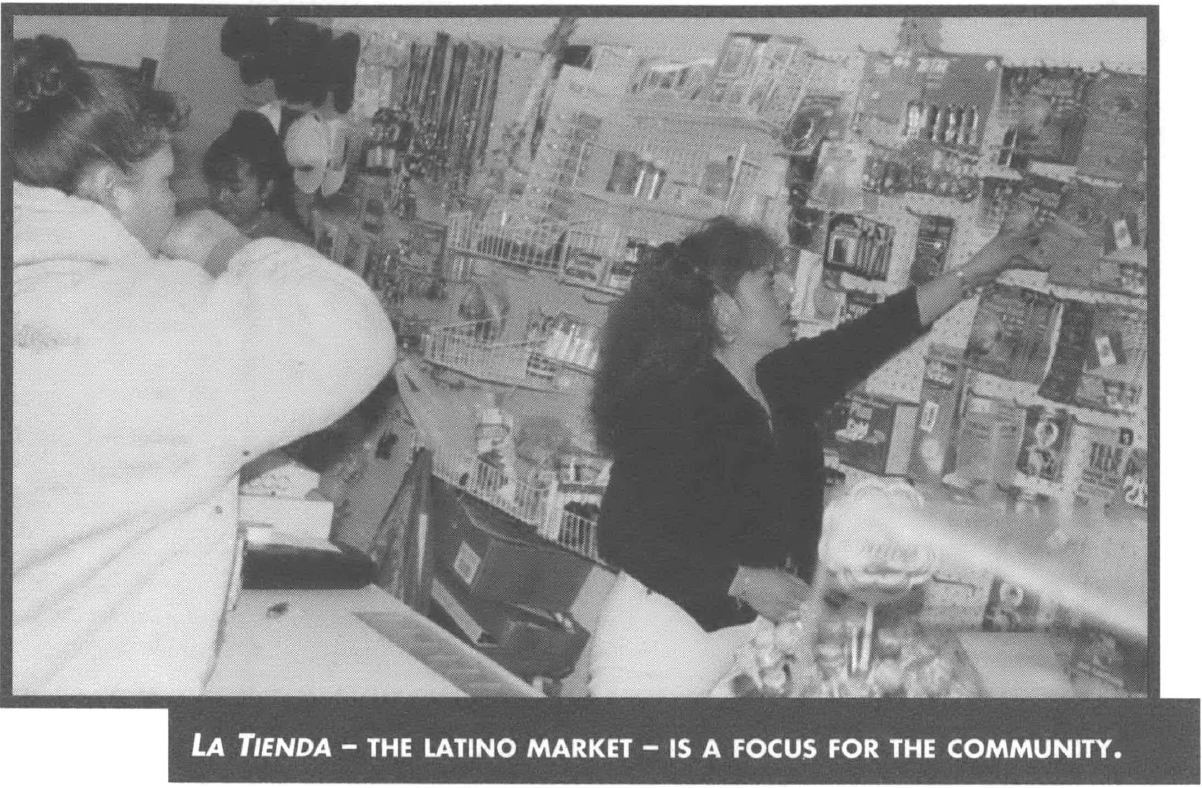

La Raza brings with it everything necessary to stay culturally alive. In small apartments and dilapidated trailers outside of Knoxville, Spanish sings back and forth. Walk into a Latino home, and the hot odors of tortillas, beans, singed meat, jalapenos and coffee invade your nostrils on welcome. Somewhere to be found and quickly offered is a bottle of Don Pedro Brandy. The conversations are long, vivacious, and last hours after neighboring Southern gueros have gone to bed.

This relatively new Southern community is as diverse as any other. Some are Mexicans, Guatemalans, Hondurans. Others are Chicanos born in California, New York and Florida. Still others (like myself) are the first generation Southern “halfbreeds,” the products of rebellious romantic love between bi-ethnic parents who dared to cross linguistic and racial borders.

We live in small towns that are run economically by white Southerners, and often politically by both whites and African Americans. Some of these leaders and their constituencies reach out their hands in welcome (such as church workers searching for someone to save, and tobacco farmers searching for cheap labor). Others curse the day of our arrival.

Some Latinos wish to fight for the development of the Latino culture in the South, shunning assimilation for the sake of “getting ahead.” Others are here just to live life in peace, dammit, and don’t stir up the waters. Truck drivers, mothers, teachers, refugees, poets, tomato pickers, writers, ex-guerilla activists, drinkers, evangelicals, Bohemian Catholics, atheists. We’ve got it all. And here, in the South, we’re right at home.

Sometimes the Latino community, in trying to deal with Southern surroundings as well as the recent events of having two (or more) cultures come together, reaches back for old words in order to articulate the new situation: Mestizo is an appropriate term. This Spanish notion originally meant “of white and Indian parentage.” It now has taken on a new social meaning for people who are of Latino/non-Latino heritages.

It seemed that, as love endures the passage of time, so does racism. When y father drove his Harley Davidson into the East Tennessee Mountains with my mother clinging to him, my Appalachian grandparents waited on the other end. According to family lore, Papaw Abe and Mamaw Mami were resting on the porch swing, staring out into the humid August day. They saw the motorcycle pull into the gravel driveway. Papaw stood, squinted through the harsh sun, and muttered to his wife, “Oh my Lord, Ralph’s gone out and married himself a goddam Apache.”

My mother’s deep dark skin, slight indigenous features, and long black hair that fell over her shoulders and back had a difficult time making it into Dad’s white world. Language also played in the tricks: though Mom had learned a great deal of English, she had never even heard of Appalachian.

My grandparents at first found her Salvadoran tongue difficult to understand. They then saw it as charming. Mother’s ways were surprisingly refined, as if she had been brought up in a good family. Their perception went from dirty Apache to Noble Savage.

At the time my parent’s marriage was an anomaly. Today there exist more examples of Southern whites marrying Latinos. Young white women who work in chicken factories meet up with the migrant population, most of which is made up of young men. Some fall in love; some men fall into opportunity, seeing as a fairly easy way to get your residency papers, and later citizenship, is to marry a gringa.

It’s risky to enter into such a relationship. Not everyone cares for the mix — just dip into any Aryan/hate website to see their perspective on such inter-ethnic minglings. Add to that the cultural and linguistic differences between Southern white and Latino immigrants, and you’ve created a hell of a struggle. Yet there are couples who make it. They stumble together and give the world those who are difficult to pinpoint in color, who are not white, who are not black or brown, who are children.

I watch children in Tennessee who grow up in both worlds, unable to decide which road to take. Their existence slaps against a society based upon a rigid racial logic. Perhaps, in their mere living, they will break the silent code that we have all succumbed to. Unless, of course, it breaks them.

In this community, language is always an issue, and also becomes a demonstration of Latino-ness. It is not necessarily a valid barometer. Such a measuring of cultural identity plays hard upon children’s psyches.

My friend Luis and I always speak in Spanish — and discuss our Spanish, and how it has changed. Luis corrected his daughter Amalia, hoping she would not forget. “No honey, don’t say dicieron, say dijeron. Where did you learn that?”

“Empuchelo! Empuchelo!” yelled one of Luis’ kids to another boy, as they pushed a dog out of the house. I was confused. Luis explained, “it’s a mixture. Push and empujar. Both mean ‘to give a push.’ So you get empuchar.”

“That’s lousy. We’re losing our language.”

Luis agreed. “That’s what’s happening, brother. Survival makes you say things and do things like you’ve never said or done before. You know how people now say enganar (To trick, to hustle)? ‘Trickear.’ You know where you buy a watch now? At a ‘watcheria.’ What are you doing when you clean the floor? ‘Mopeando.’”

I rubbed my face with my hands. I am more a traditionalist when it comes to language, especially Spanish. Having almost lost it in my youth while living in Rogersville, Tennessee, I fought with myself and the world to become fluent again. I had spent several years in Central America honing my Spanish until it could cut glass. I practiced the past-perfect subjunctive like training etymological horses to jump fences in my brain. To hear such twisted “Spanglish” coming out of Luis’ kids bit at me like treason against both our living and our dead.

Luis seemed to have read my thoughts. He chuckled, but a sadness escaped. “I wonder how my kids will talk when they’re older.”

I watch the other halfbreeds as they play together. Some of them are pochos, like my own childhood. Others are light skinned gueros, yet they speak Spanish with the lilt and singe of a proud Chicano with deep Mexican roots. They dart about the back yard as if refuting all labels placed on them. They are beyond halfbreed; that word loses all value as it falls into the trashbin of bigotry. These children are the perfect example of mestizaje.

One benefit is that they play together. As a Latino growing up in East Tennessee in the 1960s, I can vouch for one truth: The collective experience is always much better than the life lived in isolation. Together they may stumble toward the same fact, that culture cannot be pigeon-holed, that their blood knows only one body. Here in the South we find a silent people growing larger, not only with arrival, but also in birthright. They are of one sangre — the hot, living blood of mestizos, the mixtures of many into one.

We now see the birth of Latino Southerners. This should make for an exciting futuro.

Tags

Marcos McPeek Villatoro

Marcos McPeek Villatoro grew up in Rogersville, Tennessee, and San Francisco. He is the author of three books: A Fire in the Hearth; Walking to La Milpa; and the poetry collection They Say That I am Two. McPeek Villatoro and his family now live in Los Angeles, where he holds the Fletcher Jones Endowed Chair in Creative Writing at Mount St. Mary’s College. (1999)