This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

Each year since the mid-1990s, North Carolina has ranked in the top five states as a destination for new immigrants, especially Latinos. This dramatic rise in newcomers — which has doubled the state’s Latino population since 1990 — has brought with it an explosion in stories, both in the media and on the street, about heightened community “tensions.” These conflicts are said to exist mostly in working-class neighborhoods, especially between the African-American and Latino communities and center on issues of crime, competing for scarce jobs, and cultural differences.

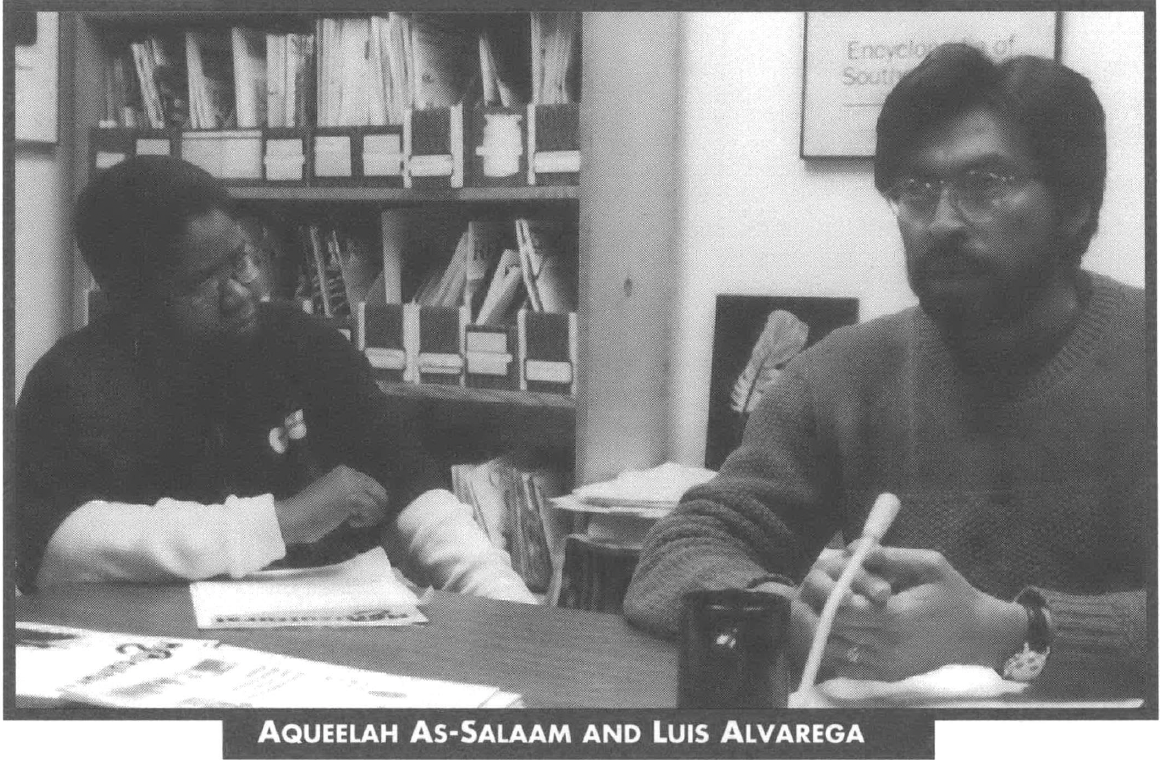

Is this tension real, or media hype? Or is this even the right question to ask? One hot summer evening, we invited several African American and Latino activists to a small roundtable at the offices of the Institute for Southern Studies to talk about what they think the real issues are, based on their work in North Carolina. The following were able to participate:

Luis Alveraga works for the Durham, N.C., public schools coordinating English as a Second Language programs and is a community organizer with La Casa Multicultural, a multi-issue organization based in Durham.

Ray Earqhart is a city worker in Durham, secretary-treasurer of the Durham City Workers Union/AFSCME Local 1194, and active in NC Public Service Workers Union (UE Local 150) and Black Workers for Justice.

Rosa Savedra is a popular educator with the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee. Previously, she was director of the Farmworker Project in Benson, N.C.

The discussion was led by Chris Kromm, editor of Southern Exposure, and Aqueelah As-Salaam, director of the Institute for Southern Studies. We asked a few questions, but mostly sat back and let the tape recorder roll on a conversation we think offers a glimpse of issues many communities — and community activists — grapple with.

“The newspaper has never been a friend”

Southern Exposure: We want to start out with how the public perceives this issue. About a year ago, in the Raleigh News and Observer, there were quite a few stories written about tensions between the Latino and African-American communities, especially in more working-class neighborhoods. These stories focused on crime, and implied there was a general feeling of ill-will. From your experience, what do you think? What are these stories missing?

Rosa: They’re missing a clue! I know from the experience we’ve had that they [the media] don’t come seeking answers, but seeking to hear the answers they’ve already got. Latinos here don’t trust the media.

There’s conflict everywhere. But to spotlight this, it’s like they use it as a tool to divide. I worry about that.

Ray: My approach to all of this is that, in my community, we’re busy working, trying to build our community. That includes African-Americans, Latinos, whites who have been thrown out on welfare reform. But the kind of cooperation that happens is not newsworthy. I could go on and throw out stories of what work we’re doing, but we’re not trying to get on 60 minutes. For us it’s survival.

We know that the newspaper is about selling papers. The newspaper has never been a friend of communities of color. It’s always been racist, it’s always been homophobic, it’s always been sexist. When you want to know what’s going on in the black community, Latino community, white community, you have to go to the community.

I’ve been disturbed about how the paper projects all these different images, but I haven’t dwelled on it, because I just know too many good stories of African American and Latino cooperation.

Luis: I used to be a media person. I started with a newspaper, and then I became a reporter for radio, and then TV. And the main job of the media person is to get the dirty story, the one that sells the most. They have to sell stories.

Rosa: But it’s just absurd to see this coming out in the papers, [this image] of tension between immigrants and African Americans. On the West Coast, you can look at Koreans versus African Americans. In Washington, D.C., you can pick any group of immigrants, and pit them against each other. Everybody knows there is tension, but what’s the purpose of these stories? It’s like we’re two groups of savage people who don’t know anything, and must be analyzed, so a solution can be thought of.

“Talk about the real tension”

Luis: There are definitely tensions [between the African American and Latino communities]. This afternoon, a man came to my door, and asked, “How many Latinos live here?” I remembered that I had called the Spanish-speaking newspaper the other day, La Connexion, and I asked the editor, “How many Hispanos do you think we have in Durham?” He said, “Officially? 15,000. But I always say 30,000.” So none of us know the dimensions of who we have here, and why they’re here.

Not knowing who’s here, and where they come from makes for uncertainty, and that uncertainty is bringing tension to the street where they live together.

Living in the same neighborhood, people find tensions. The walking in the night, the being afraid, “I don’t know you, you don’t know me.” So the tension is real, there is no doubt about it. I work with 1,700 kids, and they all talk about tensions on the bus.

So how are we trying to solve this problem? We’re training the teachers, we’re training the bus-drivers, we’re training the cooks in the school, so they know how to handle and grasp these issues.

There is violent tension, there is unspoken tension. And there are people who are working together, trying to make things happen.

Rosa: But what worries me is that everyone knows there is tension — [the issue is] how do you deal with it? A concern I have about this being in the papers, is there seems to be an ownership of this tension. It’s a white world, saying, “Here are Latino/African-American tensions, what will we do about this now?” Making those two groups feel even more powerless — not just the new immigrants, but the African-American community, too.

The majority of people in North Carolina who are Latino are farmworkers. They come as farmworkers, and end up moving on to other things. Then you have issues that come into every race and nationality, and those are class differences. . . . The issue doesn’t boil down to just race.

There are African Americans who are bankers, who have assimilated, and some Latinos as well. And they might not be sensitive to you just because they’re Latinos, or because they’re African Americans. I had a friend, who’s in government — who’s not a real friend anymore, but that’s ok — who said, “I know what it’s like, because I was in the civil rights struggle.” But she got really pissed off when I didn’t make an appointment to bring a filthy mattress to the governor’s office [in a protest of farmworker living conditions].

She’s African-American, but I don’t think this has to do with the color of her skin. It’s more about the system.

Ray: The newspaper represents corporate America. We’ve all been waiting for analysis that talks about the real tension: the tension that allows companies to violate health and safety, wages and hours, worker’s rights, that denies folks the right to unionize or to speak up about issues that impact their community. About a racist construction industry that never hired African Americans — and somehow now we [African Americans] say Mexicans are taking our jobs. We never could get hired in the construction industry.

And why are Central Americans, Latinos in this country? Corporate America. Because of what’s happening in Chiapas, with United Fruit Company, the multinationals. Because of what corporate America is doing in their countries.

A story I always tell people in my community is that there is no city in America called “Mandela.” But there are lots of cities with Hispanic names. Why is that? We came over on the boat in chains. Latinos had their country taken from them. That’s the story I tell my community when they start saying, “they need to go home.” Latinos are home.

When you talk about the bank folks, they don’t represent the interests of the African-American community. That’s some real tension: the class divide.

But despite that, when you look what’s happening across the country, there is social change, a movement building. So the newspaper, they’re not really talking about tension, they’re talking about divide and rule. They don’t want this unity between working-class whites, working-class African-Americans, working-class and farmworker Latinos, coming together around common issues.

“Start a real grassroots force”

Luis: One of the issues I have found is that the Latinos, many of us, have never experienced what it means to be organized. Especially my fellow Mexicans. We know about 1910, when there was a guy named Zapata. The founding fathers. But it’s like talking about a totally irrelevant thing. Sometimes I’ve found my fellow African Americans talk about Martin Luther King like something totally not happening right now. I am looking for that opportunity to work in the fight together, in the local neighborhoods.

Ray: You talk about block meetings and the neighborhood — you’ve got police here who are very much like the military in El Salvador; the political police is what I call them. This whole thing about neighborhood watch and community policing — it’s about a gigantic P.R. scheme by the police to get all this grant money to update themselves with all the high-tech guns and weaponry.

And it moves people away from what we’re about, which is getting to the grassroots, empowering people and letting people work together. The reason it’s not happening here goes back to those black bankers, the black bourgeoisie, who want to get a person on this commission or that council.

We’ve been trying to start a real grassroots force. I was so happy when I read about you [Luis] and Casa Multicultural because, before, the emphasis was always on cultural things — and the corporations and landlords were getting away with murder.

So it’s not just “how” you get at these questions, but who? Is it grassroots folks, or do we rely on that upper layer of African-Americans, the black bourgeoisie, or those well-meaning reporters? We’re the leaders we’re looking for.

Rosa: You know, sometimes in the urban areas — like you all are talking about — sometimes a negative side is that there are commissions. And you get drawn into working the system instead of hitting the streets. In the rural areas, we don’t have any options. It is a sink or swim situation. You hit the streets, you hit them hard. You don’t have anything to lose.

We can’t relax and let ourselves lose ground. You can’t let people get comfortable. When you raise issues, you cause change. People are now talking differently [about Latinos in North Carolina], People examine, “Can I say something or not, can I do this or not, can I get away with this or not. . . .” For people who are on the wrong side, we need to make them feel it.

Ray: The material conditions for all this organizing and unity is coming. But we’ve just got to talk more, have more conversations, and not rely on those people up top.

This takes me to when we had the sanctuary movement here. When they [the Immigration and Naturalization Service, INS] comes after some brother or sister who’s Latina or Latino, the African-American church needs to say, “Hell no, you will not take this or that person.” Like when we took in the Soweto youth, like when we were sneaking people out of Chile, housing them in the churches. When we lay this stuff out in the community, at the grassroots, people remember how we brought in folks from South Africa and Latin America.

Rosa: The disposition, I think, especially of Mexicanos, which are the majority of farmworkers in this area, is not so much — and I have a different perspective about this than Luis — is not so much that they don’t know, or have not been organized, but in Mexico there are hundreds of syndicatos [unions]. They have been unionized to death, and their unions are corrupt. So they come here with a very heightened political sense — and a lot of suspicion, you know? So it has to be worth it to you to get arrested for something.

The difficulty in organizing Latinos is often not the situation that exists here, but that we come with what we bring from our countries and we plug it in here, and sometimes it’s not a good connection.

But if you reach into the community — with someone who is of that community — we can show people that this is worth it. You’re going to make a stand here — you have to make a stand, because it’s a commitment. That’s the conscienscia that’s needed, and I think within Latino organizations, we’re not articulating our vision.

“Our issues are very similar”

Southern Exposure: So what are some of the ways you suggest we can move forward?

Rosa: Well here is an example of how not to work together. Here we have the NAACP, and it’s for people of color. They recently said, “We want you to recruit Latinos to buy membership so that they can be part of the NAACP — so that we can represent them.” It’s like, we don’t know anything about your issues. . . .

Ray: Who did they send — was it a Latino person they sent?

Rosa: Nope.

Ray: Well, ok, that tells you something right there. . . . But that’s good news to hear that the NAACP is actually trying to recruit in the Latino community. Somebody’s got it in their mind that the party’s changing, that the NAACP is for “people of color,” and that Latinos are part of that. That’s positive. But the question of having the capacity to do that — speaking Spanish, understanding the cultural issues, understanding what Latino issues are — they don’t have that.

Rosa: But that’s the work we could be doing, at the grassroots level — if we have an understanding or working relationship between us.

Luis: I think my challenge is to bring power to the people in the Hispano-Latino community, and to organize the African Americans with me, and for me to get organized with African Americans and their struggles — it’s a two-way street. Our issues are very similar.

Ray: When we talk about common ground — everybody eats. I work with S.E.E.D.S. [a community garden group in Durham] The impact this community garden in my neighborhood has had. We started to clear up this lot, and one of the old folks said, “it’d be nice if we could grow stuff.” So we started growing stuff. Two years after we got into it, Latino families moved in, and we started working with the Latino families. This has brought this community together. We have learned so much through this little garden, it’s kind of growing people together.

And I like to think that that is why nobody [Latino] has been robbed in our community. It’s respect.

Rosa: See, you reduced the vulnerability of the people because of your involvement. The rest of the people said, we’re not going to let this happen.

Ray: When you lay it out, people see the common ground. Take this whole thing about “how many Mexicans live in a house.” And you think about how, when we went to the city in the [1950s], what did we do? Tons and tons of us living with relatives, saving money, waiting to get that job and get on our feet. It made sense.

So when we take people back to where they came from, when we came to a no-man’s land, and what we had to do to survive, it comes to folks, and it takes away all this tension. It makes sense. This is what we’ve got to equip each other with. And then go out into the community and start organizing. Because our experiences are not that different.