Armed and Dangerous: The INS Beefs Up Its Forces Against Immigrants

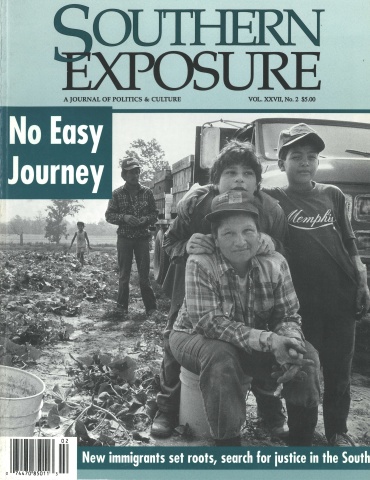

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

In the war against immigration, the nation is once again turning the South into occupied territory.

Or at least that’s one way to look at the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s “interior enforcement strategy” unveiled this spring, the latest tactic in the government’s battle against undocumented immigrants. Designed to complement the agency’s fortified presence on the U.S.-Mexico border, the strategy calls for the INS — the most heavily armed federal agency in the country — to bolster its forces in non-border states, especially in the Southern region.

A key provision in the new directive earmarks $22 million to create 50 “Quick Response Teams,” or QRT’s — offices that unite law enforcement and INS agents in the job of finding and deporting immigrants. Over 200 agents will be deployed this fall in areas that the INS claims are “suffering from a growing illegal migration problem:” Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and four Midwestern states.

The teams make official the INS’s long-standing interest in heightening cooperation between immigration and law enforcement officials. When a police officer makes an arrest, for example, QRT offices can instantly pull up the suspect’s immigration record; if the suspect is undocumented, the team can immediately begin deportation proceedings.

But while critics agree that the teams promise greater efficiency, they also say that combining immigration policy and routine law enforcement opens the door for rights abuses and heightened community tension.

“We already see that when the police and INS work together, there are civil rights concerns,” says Sasha Khokha of the National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, based in California. “We know about instances of racial targeting of motorists, of people being arrested just because they ‘looked Mexican.’ When you have a history of law enforcement being used in a racially biased way, you have a very volatile situation on your hands.”

Immigrant advocates fear that one practical result of the teams will be increased distrust between new immigrants and the police. Although immigrants are often more vulnerable to crime — for example, many don’t have bank accounts and keep money in their house — fear of police-INS cooperation could cause newcomers to avoid calling on law enforcement altogether.

“Immigrant women who are victims of domestic violence may be intimidated from contacting the police — even if they just fear being harassed by police because they look like an immigrant,” says Khokha.

Such tensions threaten to be especially explosive because QRT offices are being launched where immigration is a relatively recent phenomenon, and newcomers have fewer community institutions — such as church advocates and city agencies — to protect their rights.

“Many communities with new immigrants are operating in a climate of misunderstanding and fear,” Khokha warns. “The new policy links immigrants and people of color to crime, and is a symbol of the militarization of our immigration and law enforcement. This can only escalate the level of violence and law enforcement abuse.”

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.