This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn. — Saturday, March 18, was a watershed day in the movement for police accountability in the border town of Chattanooga, Tennessee. It was on this day that the Coalition Against Racism and Brutality marched through the city’s downtown, capping almost two decades of struggle between the African-American community and a local police department, which activists have charged with a pattern of abuse and misconduct.

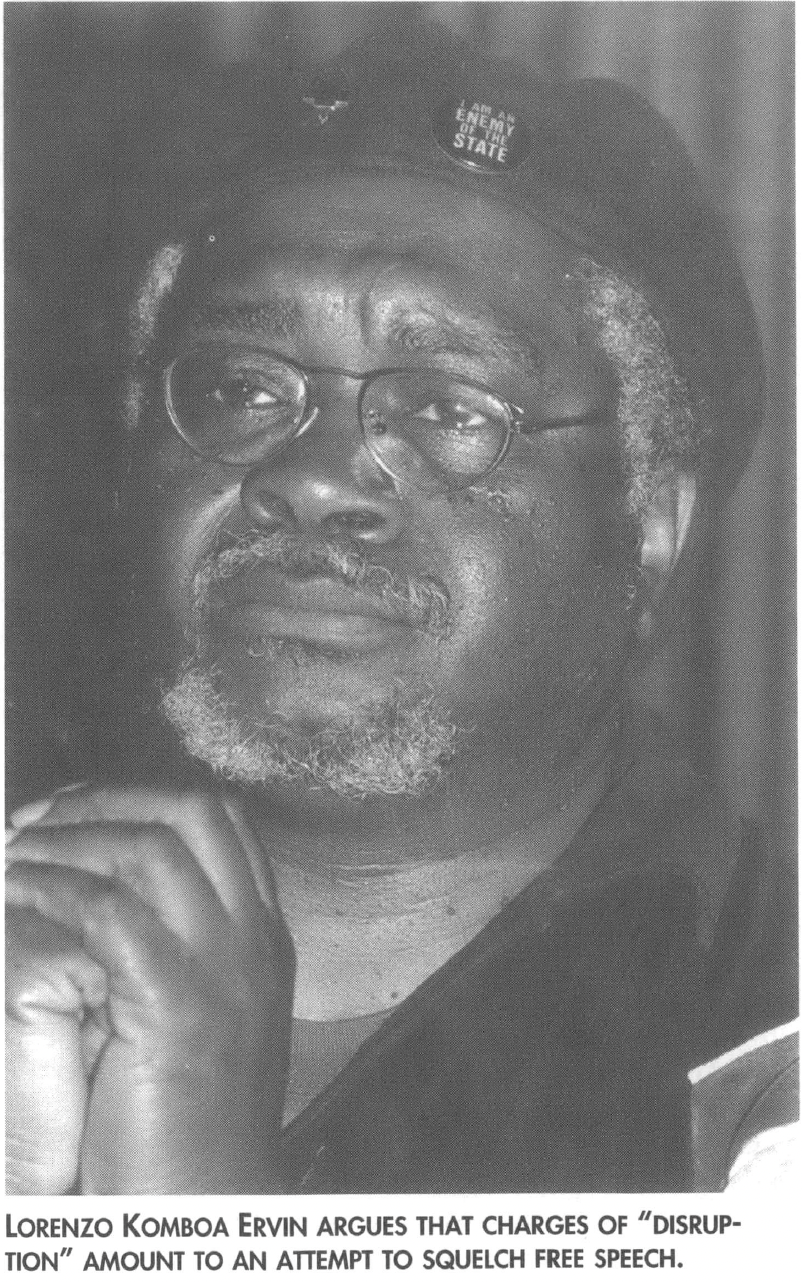

Away from the streets, in the Tennessee Criminal Court of Appeals, Saturday also brought another crucial development in the police accountability debate. The Court upheld a 1994 conviction of local activist Lorenzo Komboa Ervin for “disruption,” stemming from his anti-police brutality protests. The ruling spelled trouble for Ervin and two other activists — dubbed “The Chattanooga Three” — who were arrested in 1998, also on charges of disruption. It has also drawn attention to the entire “disruption” statute, which activists believe is a device used to squelch dissent.

“The demonstration today — after the court’s ruling — places me in legal jeopardy of being arrested just for the protests,” Lorenzo Komboa Ervin told the rally. “They denied us a permit to march, so we could all be rolled up into jail.”

“Disrupting a Meeting or Procession”

Ervin, Damon McGhee, and Mikail Musa Muhammad of Black Autonomy Copwatch were arrested on May 19, 1998 for speaking out at a Chattanooga City Council meeting against two recent police killings. The Tennessee law they were charged with is referred to as “Disrupting a meeting or procession,” and it carries a sentence of six months in state prison.

They had been told that the City Council would hear their concerns about two recent deaths at the hands of police. Just two weeks before, on May 7, 1998, a young African-American man, Kevin McCullough, was shot by police who were serving him a warrant at work. Before that, on April 28, another young African-American man, Montrail Collins, was shot 17 times by Chattanooga police. Police Chief J.L. Dotson told The Chattanooga Times that both officers were defending themselves, under the protection of both city policy and state law.

Ervin says that he was put on the agenda of the City Council to speak to his concerns about the deaths. When City Council Chair Dave Crockett failed to acknowledge him, Ervin asked when he would be able to speak.

“They said, ‘Your request has been refused,’ so I got up and spoke,” relates Ervin. The result is that Ervin, along with McGhee and Muhammad — who stood up to express their disappointment with the Council’s decision — were arrested and charged with “disturbance.”

Crockett characterizes the incident as being “more than a disturbance.” He says that the group of 150 who came to express their grievance about police abuse was “boisterous” and that they refused to wait their turn to speak. “We don’t use the special presentation time for grievances,” Crockett explains. “I think there might have been some confusion about that.”

Crockett justifies himself in having the three removed from the room and arrested. “I had some concern for the safety of the people who attended the meeting and concern for the officers,” he maintains.

Dying in the Law’s Hands

Ervin’s testimony was important to this small city nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of eastern Tennessee because of Chattanooga’s poor record on police brutality. A 1995 internal memo from the Department of Justice noted Chattanooga as number one for reported cases of police brutality of American cities with 200,000 people or less. The department’s internal investigations have consistently justified killings as self-defense. In fact no Chattanooga police officer has ever been convicted of murder.

Activists in Chattanooga fighting against police brutality have taken another blow in a struggle that has as much to do with the right to civic participation as the right to not be threatened with bodily harm. University of Tennessee law professor Dwight Aarons filed a friend-of-the-court brief asking the Court to justify the constitutionality of the statute, which he suggested could be used at the discretion of the City to silence unpopular speech.

“A challenge to the constitutionality of a statute is normally a difficult endeavor,” says Aarons. “I’ve tried to point out to the court the difficulties involved in reading the statute to maintain that the statute, as presently written, does not infringe on a defendant’s constitutional rights.”

Aaron argues it is a hard law to defend, though. “Texas law, which is the model for the Tennessee statute,” he relates, “has been found to be over-broad.”

The Associated Press has reported two cases in which community members have successfully challenged such restrictions and won. Elizabeth Romine was found “not guilty” of obstructing government operations for speaking out of turn at a Florence, Alabama, City Council meeting. Similarly, a Michigan judge issued an injunction last year barring city officials from keeping critics of Battle Creek Police Chief Jeffrey Kruithoff from speaking out against him during open meetings.

Silencing Dissent

Ervin feels strongly that the City of Chattanooga is more interested in stifling dissent than keeping the peace. “This is a tourist town. Tourism is the number one industry. In their view,” he says, “they can’t afford to have a negative position about authority.”

“There is a long history of repression of radical activity and Black-led political causes in Chattanooga.” Ervin points to the prosecution of the four principal leaders of the Chattanooga Black Panthers in 1972, which effectively neutralized the local chapter of the party. Ralph Moore, Gerald Edwards, Ray Lindsay, and Madonna Storey were all charged and convicted of extortion by the Chattanooga Criminal Court. This was during the era of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program in which the agency carried on an intensive campaign of repression against the Panthers, as well as infiltrating the organization with provocateurs to engineer a national split between the east and west coasts. In smaller chapters such as Chattanooga’s, aggressive investigation and prosecution were used more effectively.

Ervin is only aware of the “disturbance” statute being used twice — in his current case and against him once before in 1993. At a police memorial, Ervin and eight others were arrested for counter-demonstrating to memorialize individuals who had died at the hands of the police. They were protesting the refusal of a Hamilton County grand jury to indict the law enforcement officers responsible for killing Larry Powell, who critics charge was a victim of “driving while black.” Powell was choked to death by the police.

Crockett agrees that the statute is rarely put into use. “I only remember one other incident when someone was asked to excuse themselves and that was amicable because the person was inebriated.”

Aarons concurs that the case is a legal rarity. “My research of both reported and unreported cases has not uncovered any case involving a prosecution under the statute,” he testifies. “Lorenzo’s case appears to be a first.”

The recent movement against police abuse in Chattanooga goes back to Concerned Citizens for Justice, founded in 1984 by Maxine Cousins. Cousins’ father, Wadie Suttles, mysteriously died in a Chattanooga jail in December 1983. Cousins and others in Concerned Citizens felt strongly that Suttles had been murdered at the hands of the police.

A Community Comes Together

Cousins’ quest for justice over the past 16 years highlights the dogged persistence of Chattanooga’s struggle against police brutality. “My father was arrested for disorderly conduct,” she says. “He was taken to the hospital three times in the seven days he was in jail. On the third time he was dead.” She tells of an unbowed Black man who was beaten on the head with a steel rod wrapped in leather until his skull cracked and his head started bleeding internally. “He started screaming out for help and nobody came.”

Initially, there was a strong organizational effort to respond to the tragedy. Cousins believes the NAACP, Operation Push, and other groups were disingenuously posturing for leadership instead of working together to build resistance to police brutality. She was frustrated that the lawyer who brought a criminal case against the Police Department, seemed to de-polticize the issue.

The next year she and a friend met the mother of Emmett Till at a conference in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Ervin stresses that the push to make the Chattanooga police accountable came from ordinary people. “Established Black organizations such as the NAACP were not in the forefront of the struggle and that’s why the Coalition was founded. It was individual people in the community who had suffered from police brutality who stood up.”

In their experience fighting police abuse in Chattanooga, the Coalition has seen its ups and downs. Copwatch programs have been used intermittently to put police brutality in check — but at a price. Cousins lost her job at the Tennessee Valley Authority because of harassment from her supervisor who disapproved of her defiant position against the police. At one point, Chattanooga instituted a police review panel but Ervin and others in the Coalition felt that it was ineffective because it was dominated by the police themselves. “The police cover-up had been compared to Emmett Till’s case,” relates Cousins. “Till’s mother was describing some of the emotional things that come up, which I was also experiencing.”

Frustrated with the lack of progress in the case and determined to take charge of her life, Cousins decided to found Concerned Citizens for Justice. “We wanted to be able to move without getting anybody’s permission,” Cousins insists. “We started holding prayer vigils for my father’s case outside the jail even though we didn’t realize that it was a protest.”

In 1988, this organization evolved into the Adhoc Coalition Against Racism and Police Brutality.

Even if the tide of police abuse has not been stemmed, Ervin feels that there is more awareness and willingness to acknowledge the problem. “100 people called into this local radio show to say that they’d been harassed by the police. I don’t think that’s changed (from the past). 35 people have been killed by the police in the past decade in Chattanooga. Four people have been killed in the past eighteen months. One person died in holding, and the police called it a suicide. People they kill right on the street they call a suicide.”

The Chattanooga Police Department would not comment on any of statistics of police killings put out by Ervin and the Coalition (“I don’t want to get into a war of words with that group,” said Media Director Ed Buice.)

Ervin is a veteran of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was founded in 1960. Much of his sense of local, grassroots struggle came from those years of organizing during the civil rights movement, but much has changed. “SNCC arose at a time when it was possible to organize around mass events; that can’t be replicated.”

“We thought of ourselves as organizers, not charismatic leaders,” Erwin emphasizes. “That was our political education.”

But most importantly, it’s crucial to stay focused in the present. “The civil rights movement went past this place. That’s why the activism of Maxine Cousins and the activism starting in the early ’80s is important for Chattanooga.”

Cousins comments that there “have been some concessions made because of the organizing.” However, on the day after the acquittal of four New York City police officers charged in the Amadou Diallo case, she was dismayed at the current state of community-police relations on a national level.

“The Diallo case has brought back the Taney Ruling of 1896,” says Cousins. “It reinforces for African Americans that ‘a Black man has no rights which a white man is bound to respect.’”

“There has to be a national movement to make the police accountable,” Cousins insists.

While unsure of his legal options for maintaining his freedom and continuing the struggle, Ervin remains committed. “Keeping a spotlight on the police and monitoring their activity is the only way to combat police abuse.”