This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 1, "25th Anniversary Edition." Find more from that issue here.

“The story of Southern Exposure,” says Bob Hall, a founder of the magazine and its longest-lasting staff member, “begins with people marching in the streets.”

There’s no doubt that Southern Exposure was a child of the ’60s generation. Yet by the time the magazine was launched in 1973, the activist fires that had forged the consciousness of Hall and other civil rights veterans at the Institute for Southern Studies were already beginning to cool. War lingered in Vietnam, Nixon stood tall, and people filled with hope only a few years before began to doubt the prospects for change. “The topography of American political culture in this strangely suspended season,” journalist Andrew Kopkind would write that year, “is strewn with the skeletons of abandoned movements, lowered visions, and dying dreams.”

Just the time to start a progressive journal, the Atlanta-based crew decided. More than ever, they reasoned, Southerners dedicated to change needed a forum to share ideas, a place to find inspiration and take activism in new directions. “It was a way to carry on an edge to critical thinking in the South,” Hall remembers. “To help us answer, ‘How do we look at our region? What’s next? What do we do?’”

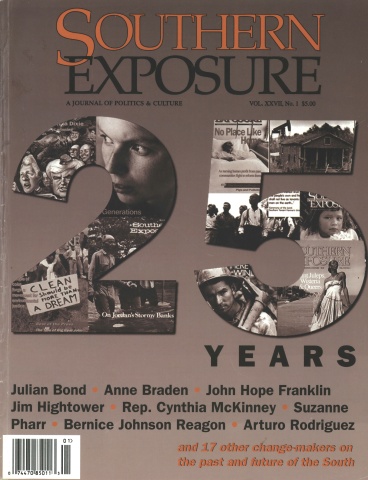

Over the next 25 years, through twists and turns of staff, strategy, and format, Southern Exposure would always return to these central themes, grappling with — and often offering innovative answers to — the questions of how we view the South, and what could be done to change the region for the better. By combining analysis and action, and using cutting-edge tools such as strategic research and oral history to link the two, SE quickly gained a national reputation and began making its mark in Southern history.

Southern Exposure became perhaps best known for its strategic research and tough investigations exposing abuses of power, naming names of the interests that were threatening a decent way of life in the region. While the rest of the country dwelled on the South’s “race problem,” SE portrayed a more complicated reality, drawing attention to economic players such as reckless corporations and “New South” elites who often escaped scrutiny by the mainstream media.

These investigations took readers into the Kentucky mines and the Carolina mills, the poultry plants and the mega-hog farms, to see firsthand the tragic costs of putting profit before people and the land. But this wasn’t digging up dirt for dirt’s sake — it was an attempt to arm unions, civil rights groups, and other activists with the information they needed to raise awareness, change laws, and create a more just South.

Only in Southern Exposure could one find a regular feature like power structure “spider charts” — illustrated maps of the corporate web of influence in society, designed as a tool for action. “Organizers used those spider charts to see connections,” says Jim Overton, who started working with the magazine in the mid-70s. “You could identify corporate allies and targets that could bring change,” a strategy used successfully by many groups connected to the Institute and SE.

Southern Exposure’s hard-hitting investigations were balanced by the journal’s cultural side, which aimed to cut through tired stereotypes and offer a portrait of Southern life that emphasized the region’s progressive history and enduring positive traditions. Central to this project of reclaiming the South was the journal’s pioneering use of oral history, which let ordinary people — be they sharecroppers, striking tobacco workers, or the children who integrated Southern schools — speak in their own voice, re-telling history from the “bottom up.”

What the historians found was an unbroken history of Southerners engaged in social change — an eye-opening experience for SE’s editors and writers, as well as readers. “We were learning about a legacy of struggle we had not been aware of,” says founding editor Leah Wise, who led interviews and compiled personal histories for early editions of the journal. “It was an amazing discovery.”

“When people talked about their moments of struggle, they remembered it keenly — even while other memories fell by the wayside,” she recalls. “When they were active in changing the world, they were most alive.”

Oral history also had relevance to more recent activism — revealing moments in history of successful cross-racial organizing, and reassuring present-day change-makers that they were part of a proud tradition. “When you learned that you weren’t alone, that served as a kind of springboard for activism,” says David Cecelski, an oral historian who still writes for the magazine. “People really did consider oral history part of an organizing strategy.”

And then there are the issues of SE that broke the mold and continue to defy categorization. Special editions on Southern music, folklife, and sports — and offbeat works like an unsung but brilliant issue on Southern buildings — revealed the eclectic curiosity and deep love writers and editors had for a region many of them called home. Copies of “Working Women” and “Elections” became standard organizing “how-to” manuals, while “Generations: Women in the South” — the best-selling issue ever — offered new notions of strategy and history to fill a deep void in our region’s self-understanding.

The common thread was that all of these editions helped us understand the South a little bit better, bolstering our courage and determination to fight to make it our own. Each issue was also driven by a relentless drive for excellence — as early-1980s editor Marc Miller notes, “we felt the stakes were too high, not to do the best job we could.”

And sometimes, the establishment gatekeepers stood up and took notice. Beginning with the George Polk Award in 1979 (for which, the editors wrote, they were “deeply appreciative — even if the award didn’t come with a fat check!”), Southern Exposure went on to be honored with some of the most prestigious awards in the business, including the Sidney Hillman and National Magazine Award.

More often, mainstream media paid SE the compliment of imitation, using the journal’s groundbreaking research to inform their TV and daily paper coverage, with and without attribution.

Not to say Southern Exposure didn’t make its share of mistakes and missteps. Important stories were missed: for example, the cause of gay and lesbian liberation rarely received full “movement” status, which may explain the magazine’s silence on the AIDS crisis which has disproportionately ravaged Southern communities. And the need to maintain a sense of humor in the face of injustice has been a perennial bone of contention voiced by newcomers and old fans alike (see “It’s Still the South,” p. 46).

SE has also had to learn to adapt to changing times. A shift in political winds during the 1980s made speaking to a broader audience a necessity. The journal went bi-monthly, and reinvented itself again in the latter part of the decade, going back to a quarterly although adopting a popular “magazine” format.

In today’s age of hot-wired info, “news you can use” and predatory media conglomerates, Southern Exposure once again is entering a new context. But the need for an independent voice, offering reflection, interpretation and strategies for change — in short, asking the basic questions of who are we as a region, and what can we do? — is perhaps stronger than ever. “Looking back, I think our approach still holds up,” Hall says. “It’s right on the money.”

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.