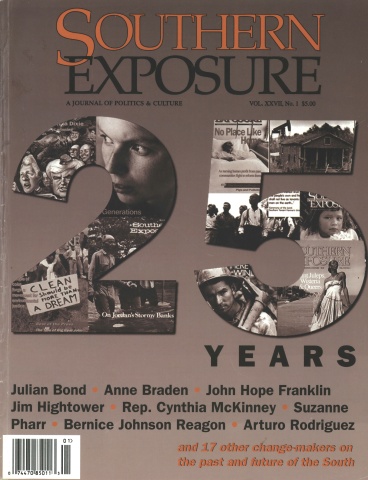

25 Voices for Change

By The Editors / March 1, 1999

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 1, "25th Anniversary Edition." Find more from that issue here.

How has the South changed in the last 25 years? Or has it really changed at all? And what would it take to make a better South than we have today?

To help answer these questions, we asked 25 leading Southern “change-makers” — from activists to academics, poets to politicians — to give us their view from the trenches. We asked each to write on two themes: How has the South changed, and what have those of us interested in progressive change gained in the last 25 years? And second, what are the key challenges we face for creating a better South in the next 25 years?

The following are what these 25 change-makers had to say:

Julian Bond

“A New Crusade for Racial Justice”

“Lay Claim on Tomorrow”

“Facing the Right’s “Divide and Conquer” Strategy

Sermon: “Finding and Telling the Truth Takes Persistent Spirits”

The Chilling Effect of Repression

From Segregation to Privatization

“Cease building walls, begin building bridges”

“Times that call for uncommon courage”

“A Sense of Place”

“It’s not enough to be progressive — we must be aggressive!”

Race: “The Old Categories are Inadequate”

“The Fight Is for Control”

Political disenfranchisment: “One of the next civil rights issues”

“Try to live our vision”

“Yours in the Struggle”

“I Think of Bulldozers and Republicans”

“And I Come Singing!”

The Southern Paradox

“There’s a growing sense of pride”

Inclusion, coalitions, and power

“I’m More Determined than Ever”

“The issues are now geared toward economics”

“It feels like, just to be able to sustain life is a victory!”

“Mass, non-violent direct action: it keeps us close, and it works”

Tags

-

Tags

- southern exposure

- liberation movements

- freedom movements

- julian bond

- Anne Braden

- pat bryant

- mandy carter

- kim diehl

- ajamu dillahunt

- scott douglas

- John Hope Franklin

- Jordan Green

- bob hall

- Bob Hall

- jim hightower

- alicia maria junco

- kamau marcharia

- cynthia mckinney

- tema okun

- john o'neal

- suzanne pharr

- bernice johnson reagon

- diane roberts

- arturo rodriguez

- june rostan

- malika sanders

- hollis watkins

- Jr.

- leah wise

- harmon wray

Knowledge matters.

From exposing abuses of power and holding powerful interests accountable to elevating the voices of everyday people working for change, Facing South has become a go-to source for investigative reporting and in-depth analysis of Southern issues and trends.

Support Facing South with a tax-deductible donation.

We are building a better South.

The Institute for Southern Studies is committed to being an essential resource for voices of change in the South. Please join us and help bring lasting social and economic change to the region.