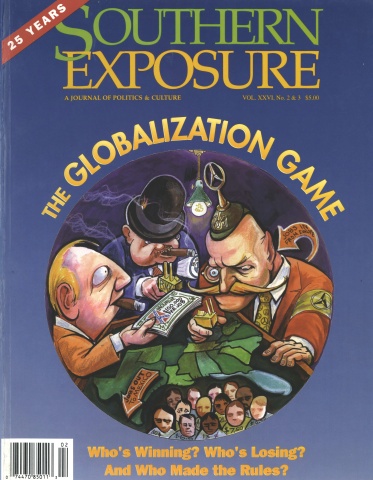

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

When workers at the Tultex textile plant in Martinsville, Virginia, started organizing for a union, company managers told them they had to watch a videotape. While sitting in mandatory “captive audience” meetings, workers saw graphic footage of boarded windows and padlocked gates at closed-down textile plants in New Jersey — plants that had also been organized by the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union.

The implications of the video — which the company also showed on the local cable access station — were clear: This will happen here if the union comes in.

What happened in Virginia was not unique. Especially after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), plant-closing threats and actual plant closings have become extremely pervasive and effective components of employer anti-union strategies in the United States.

From 1993 to 1995, employers threatened to close their plants in the majority — 50 percent — of union elections to be certified. In another 18 percent of the campaigns, the employer threatened to close while the first contract was being negotiated, after the election was won.

Some of these threats had teeth. Nearly 12 percent of employers followed through and shut down all or part of the plant before a contract was negotiated, and another four percent closed down the plant before a second contract was reached. This 15 percent shutdown rate is triple the rate in the late 1980s, before NAFTA went into effect.

In short, where employers can credibly threaten to shut down or move their operations in response to union activity, they do so in large numbers — a trend which has had strong implications for union organizing across the country.

Threats, Open and Veiled

Plant-closing threats come in a variety of guises. Veiled and verbal threats are the most common, which is not surprising given that direct, unambiguous threats to close plants in response to union organizing are clearly in violation of the law.

In more than one in ten cases, according to organizers, employers directly threatened to move to Mexico if workers voted to unionize. Threats ranged from attaching shipping labels to equipment throughout the plant with a Mexican address, to posting maps of North America with an arrow pointing from the current plant site to Mexico, to a letter directly stating the company will have to shut down if the union wins the election.

In March 1995, ITT Automotive in Michigan parked 13 flat-bed tractor-trailers loaded with shrink-wrapped production equipment in front of the plant for the duration of a UAW organizing campaign. The company posted large hot-pink signs on the sides of the vehicles which read, “Mexico Transfer Job.” The equipment came from a production line the company had closed without warning. ITT Automotive also flew employees from its Mexican facility to videotape Michigan workers on a production line which the supervisor claimed the company was “considering moving to Mexico.”

In a captive-audience meeting speech during a Teamsters organizing campaign, Robert Epstein, president of AJM Packaging and Roblaw Industries in Folkston, Georgia, made a more subtle but no less direct and unambiguous threat.

“We’ve been here in Folkston going on 10 years, we’ve enjoyed the stay in Folkston. Our company is growing . . . by leaps and bounds,” he said. “It looks like now that we can’t count on Folkston to be part of those future plans and part of that future growth. But nothing is said and done and the fat lady hasn’t sung yet and quite frankly we won’t know what’s gonna happen around here, I guess until May 12” — the date of the union’s election vote.

In other cases, the threats were much less complicated. In the Texas Rio Grande Valley, Fruit of the Loom posted yard signs in the community that said, “Keep Jobs in the Valley. Vote No.” The company also hung a banner across the plant that warned, “Wear the Union Label. Unemployed.”

Companies have used different approaches to relay threats. A common approach used by supervisors was to call two or three workers together for a meeting to give them the “straight facts” about unionization. The supervisor would explain how she was concerned about the union campaign because she “had much to lose.” meaning her job, if the union was certified. Other supervisors would claim that they had “inside information” about plans to move the plant.

Other companies distributed leaflets in the plant or mailed letters to all employees’ homes making veiled plant-closing threats. A final tactic used by companies was to spread plant-closing rumors. In one case involving the glass and chemical maker PPG Industries, a plant manager’s son claimed that he had overheard a phone conversation in which his father discussed plans to close the plant and move it to Mexico if the union was certified.

An Effective Anti-Union Strategy

Plant-closing threats matter. From 1993 to 1995, unions won elections 33 percent of the time in units where plant-closing threats occurred — significantly less than the overall win rate of 40 percent.

The rate of union success dropped significantly — down to 25 percent — in cases where employers put direct threats into writing. Additionally, more than half of the organizers in cases where threats occurred reported that the fear of plant closings contributed to the union withdrawing the petition before the campaign went to an election.

And the threats continue after a union wins recognition. In the period studied, some absolutely refused to bargain with the union, making clear that they would shut down rather than be forced to sign a union agreement. Others focused on how, now that the union had won the election, the company was re-evaluating operations and considering transferring work to non-union facilities or contracting out bargaining unit work. More common was the threat that the employer might go out of business if the union succeeded in bargaining the kind of agreement that they were attempting to reach.

According to union negotiators, the primary adverse effect of these post-election plant-closing threats was to seriously undermine the quality and scope of the first agreement. In the most extreme cases, the threats led to the union withdrawing from the unit or losing a decertification election, as workers began to question the ability of the union to reach an agreement without severely risking their job security.

We’re Closing!

Actual plant closings are the most severe form of anti-union employer activity. From 1993 to 1995, employers imposed this “death penalty” sanction in a surprisingly high number of cases. In almost 12 percent of the cases where the union won the election, and another four percent after a first contract was reached, there was a full or partial plant closing.

In most of these cases — 85 percent — the employer had directly threatened during the organizing campaign to shut the plant down if the union won the election, and then followed through. In the case of the United Steelworkers of America campaign at St. Louis Refrigerator Car Company, the company had repeatedly told workers that if they gave the company trouble it would transfer operations to a newer non-union facility in Akron, Ohio. Ten days before the election, the company agreed to voluntarily recognize the union, only to shut the facility down one week later.

The 15 percent incidence of plant-closings represents an upsurge from the five percent closing rate in the 1980s and early 1990s. The tripling of the rate in the years since NAFTA was ratified suggests that the agreement has both increased the credibility and effectiveness of closing threats for employers, and emboldened increasing numbers of employers to act upon that threat. In fact, in several campaigns, the employer used media coverage of the NAFTA debate to threaten workers, stating that it was fully within the company’s power to move the plant to Mexico if workers were to organize.

Toward a Threat-Free Workplace

With today’s fears of downsizing and job loss, many workers take even the most veiled employer plant-closing threats very seriously. When combined with employers’ other anti-union tactics, plant-closing threats appear to be extremely effective in undermining union organizing efforts.

And the fears build on themselves. Union organizers say that one of the most effective components of employer threats are the photos, newspaper clippings, and video footage of plants which shut down in the aftermath of a union campaign.

Plant-closing threats pose new challenges for unions, which can learn from the success and failures of past organizing efforts. Union victories like the Electronic workers’ (IUE) campaign to organize production workers at an auto parts plant in Texas, or the Steelworkers’ 1995 campaign to organize a Unarco wire fabricating plant in Oklahoma, were able to overcome threats of moving to Mexico through the intensity and quality of their campaigns.

Success for unions has hinged on a rank-and-file intensive strategy, backed by significant staff and financial resources and based on building community solidarity. Unions who have lost elections due to plant-closing threats have tended to run much less aggressive campaigns, with an emphasis on less personal tactics such as mass mailings, leafleting, and large meetings.

As for current U.S. labor laws, the penalties for illegal plant-closing threats and other labor-law violations are extremely limited. If employers fire union activists, the worst penalty they face is reinstatement and back pay for the dismissed workers, with no possibility of punitive damages. If employers refuse to negotiate, they merely receive another order telling them to bargain in good faith. In the case of Sprint’s La Conexion Familiar, where the National Labor Relations Board found that the company had committed over 50 labor law violations, the only penalty was that Sprint reimburse fired workers back pay and find them comparable jobs at other Sprint locations.

Things could be different. Where workers choose unions free of plant-closing threats and other forms of intimidation, the union success rate is dramatically higher. For example, in the public sector — where employers are less likely to mount anti-union campaigns — workers vote for unions in large numbers. In contrast to the private sector win rate, which has averaged less than 50 percent for more than a decade, unions in the public sector enjoy win rates averaging more than 85 percent.

Reaching such a “level playing field” for all workers will require the expansion of worker and union rights, and of employer penalties, in the organizing process. These changes should be accomplished both by significant reform to U.S. labor laws and by amendments to the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation, which provides an enforceable code of conduct for countries covered under NAFTA. This code must include both restrictions on the ability of companies to shift their operations to other countries to avoid unionization and guarantees to organize free of interference and intimidation.

Most important of all, the new codes must include meaningful penalties for violations of those rights. Then, and only then, will workers be able to exercise their democratic rights to have an independent voice of their own choosing represent their interests in the workplace. And then, and only then, will employers no longer be able to flagrantly violate labor laws at the expense of their workers’ dignity and well-being.

Tags

Kate Bronfenbrenner

Kate Bronfenbrenner is Director of Labor Education Research at the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University. (1998)