This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

At night, a string of lights illuminate the sky of the rural 100-mile stretch of land between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana. In daylight, this brightness fades, giving way to clouds of smoke that rise from a veritable landscape of giant mechanical structures. These structures belong to 138 companies that comprise a virtual “who’s who” of the petrochemical industry: Texaco, Borden, Occidental Chemical, Kaiser Aluminum, Chevron, IMC-Agrico, Dow, Dupont, and many others.

State and local officials call this progress. The petrochemical industry, they say, contributes billions of dollars and countless jobs to the state and local economies.

Residents who live in the surrounding area have dubbed the industrial colony “Cancer Alley.” For them, the industry has brought few jobs, destroyed the natural environment, and brought a host of illnesses that they attribute to emissions from the plants. Residents in the area, who are primarily minorities, also call the industry’s invasion environmental racism — the targeting of communities of color for undesirable facilities.

A number of studies suggest that such claims may are not unfounded. Nationally, a 1987 study by the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice called Race and Waste found that blacks were four times more likely to live in areas with toxic and hazardous waste sites than were whites. A 1992 investigation by the National Law Journal found that even when the government does enforce environmental regulations and fine companies, fines are much higher in white communities than in black ones. Even in Louisiana, reports by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and an unreleased report by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region Six have raised concerns about the location of chemical plants and the possible impact on the health of nearby residents.

These reports and increased activity by environmental justice groups across the country prompted President Clinton in 1993 to sign an executive order directing federal agencies to investigate the petrochemical industry’s disproportionate impact on people of color. The Clinton Administration also set up an Office of Environmental Justice at the EPA, and the state of Louisiana passed its own legislation on environmental racism.

None of these efforts have helped people in Cancer Alley. Here in the chemical corridor, where the chemical industry is king, such legislation means little. But in one small town residents hope to break this trend.

Convent, a small, tired town of a few hundred people, is divided by the Mississippi River and lies in the heart of Cancer Alley. A number of modest homes, small churches, and a few stores contrast run-down mobile homes and other dilapidated structures where people continue to reside.

Like the rest of Cancer Alley, Convent has its share of industry. IMC-Agrica, a Japanese owned company, has set up a base here, and its plant looms over River Road, the narrow two-lane highway that runs in and out of town. The road is infected by a nauseating stench, which emanates from the plant at all times. A giant grain elevator thrusts itself heavenward, and sends dust clouds earthward, which some people say destroy the paint on their homes and cars. Ships and barges, transporting products and raw materials for these industries, creep up and down the river.

According to the EPA’s latest yearly toxic release inventory, over 23 million pounds of toxins were released into the air. The majority of these releases were in two zip codes, both primarily inhabited by black residents. It’s here that Shintech, a Japanese company, hopes to build the nation’s largest Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) production plant. If built, the plant would add 600,000 pounds of air pollution. The plant hopes to start building soon on 2,400 acres of land, three old sugar cane plantations where blacks once toiled as slaves.

The symbolism is not lost on Jerome Ringo, a former petrochemical worker who is helping to organize local citizens here to stop the construction of the plant. “The descendants of the people who work the sugarcane plantations still live here,” Ringo says. “Much like their ancestors, these people have nowhere else to go. The people can’t leave and the industries won’t leave.”

Clifford Roberts, 71, was born and raised in Convent. Except for a stint in the Marine Corps and a couple jobs elsewhere, he has spent his whole life here. He had hoped to retire to the house he bought more than 30 years ago. But the encroachment of the petrochemical and other industries has him fighting for his peace of mind.

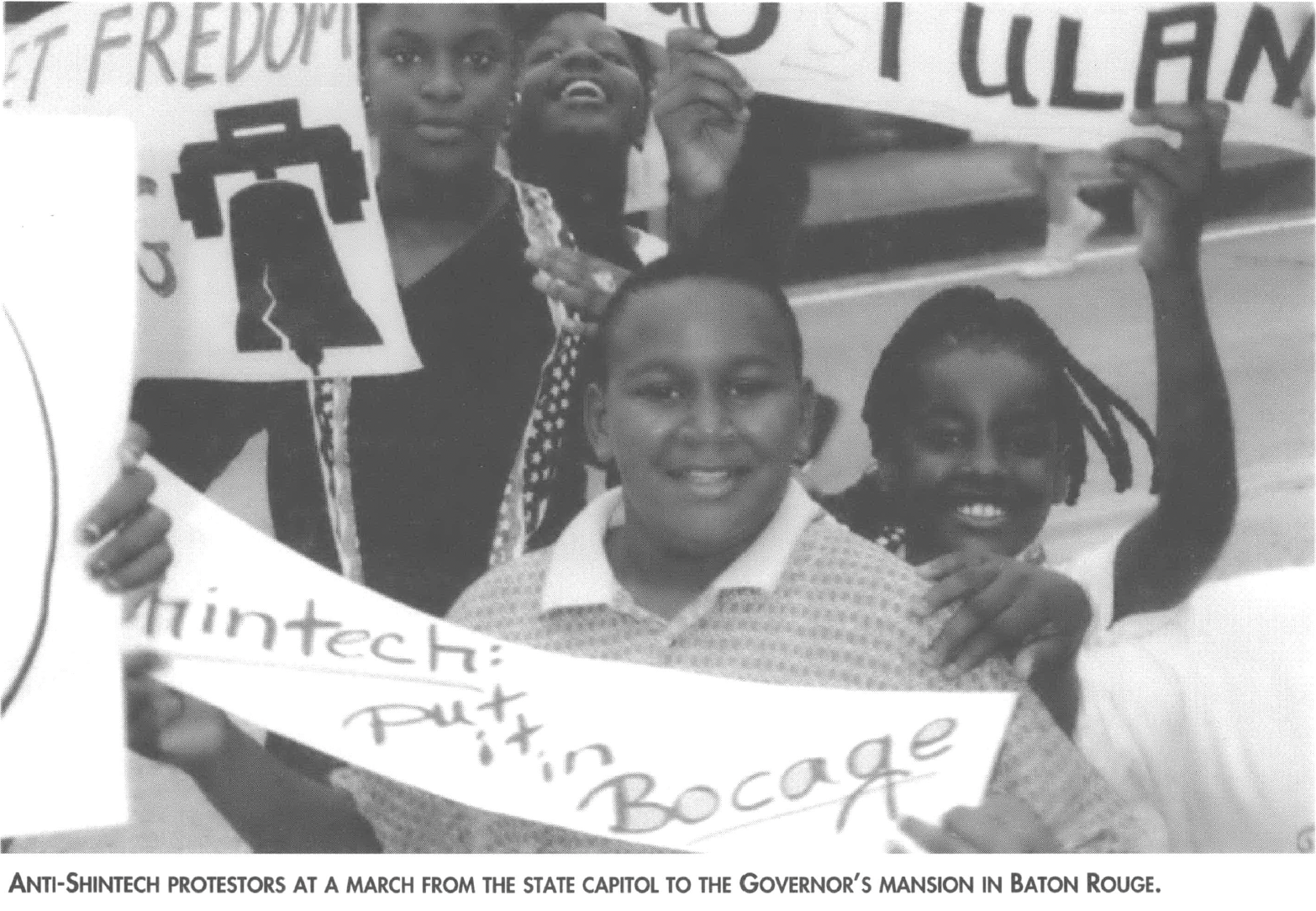

Along with a group of both black and white residents who call themselves the St. James Citizens for Jobs and the Environment, Roberts and his wife Gloria, a retired school teacher, have been working to organize locals to stop the siting of Shintech. The group has gathered more than 1,000 signatures on petitions, and at the initial public hearing for Shintech’s local permits, they got more than 300 people to show up in protest. Not an easy task in an area where a significant part of the population is impoverished and nearly 47 percent are without a high school education.

Organizing is made more difficult by the fact that many people are desperate for jobs. After the initial public hearing, Roberts says the numbers of people willing to attend meetings has dropped. “Most people are afraid to come forward,” he says. “Many are looking for jobs or they might have a relative who works for the parish and they’re scared that person will be fired if they say something.”

Pat Melancon, president of the St. James Citizens for Jobs and the Environment, claims that people are simply overwhelmed. “Whatever we do, Shintech and its people match everything we do,” she says. “If we take out an ad in the local papers, they take out a full page ad. People tend to get discouraged when faced with these kinds of odds.”

Melancon points to the initial public hearing for Shintech’s local permits as an example. At that hearing, she says, state and local officials, who support industrial growth, stacked the deck. Most of the people who were called to testify early in the meeting were representatives of Shintech flown in for the occasion, local officials who support the company, and representatives from the state chemical industry, who, according to Melancon, “simply overwhelmed people with technical jargon.”

The first citizens who opposed the plant didn’t get to speak until 11:00 p.m., she says. “Most people had gone home by then. They couldn’t afford to stay.”

Like most people here, what worries Roberts and Melancon most is the health impact of Shintech siting in Convent. The company’s property abuts black neighbors on both sides. Three schools — where the majority of students are black — and a public housing facility are close to the plant’s property. While state and local officials have denied chemical exposure to be a cause of illness, nearly everyone in these communities can name someone who has died of cancer, which they blame on toxic chemicals. They fear that the plant will add to the health problems that people in Convent already have.

“A lot of people have cancer and illness like influenza,” says Roberts, who recently lost a brother to colon cancer. “We know it’s the chemicals that’s causing these illnesses no matter what they say.”

What is of particular concern is the production of PVC at the proposed Shintech facility. PVC is commonly used in a number of products, including pipes, wire and cable coating, credit cards, and packaging materials. Industries who make PVC like to boast that it is a product necessary for everyday life. But the production of PVC is a process far from safe for everyday life.

The main ingredient in PVC is vinyl chloride, a colorless vapor with a mild, sweet odor. According to data from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, vinyl chloride can cause cancer and a host of other medical problems. Not an enticing prospect for the numerous people here who say they suffer from a number of cancers.

Newer research indicates that PVC might also cause illnesses other than cancer. Many scientists now suspect that vinyl chloride causes reproductive problems such as low sperm count, which can lead to infertility.

“They’re just adding stuff on top of other chemicals,” says Elmenda West, an elderly black woman who lives just down the road from where the Shintech plant would be located. “ Shintech needs to go home. We don’t need any more chemical plants here; we’ve got enough.”

David Wise, a project manager for Shintech, is quick to point out that the company was asked to come to Convent. The company, he says, has established a good relationship with local citizens. He blames much of the opposition on environmental groups and people who live miles from where the plant would be built.

With 1,000 signatures opposing Shintech’s inception, Wise’s claims are subject to debate, but there is little doubt that the company has support where it counts — from local and state elected officials, a high-powered public relations firm, and a medical report downplaying the environmental causes of cancer.

The parish president of St. James, Dale Hymal, has been solidly behind the plans to build the plant in St. James, some say to the point of lobbying for the company while ignoring the concerns of residents. On April 9, 1996, before Shintech had even submitted a formal application for permits, Hymal wrote the company offering the commitment and support of his office in securing a new plant site.

The parish director of operations, Jody Chenier, faxed a list of the local coastal zoning committee and planning committee members to Shintech. The purpose of this fax was unknown, but the membership of the committees was broken down by race and occupation. Background comments on each member were included. For one black member on the coastal zone committee Chenier wrote, “Very quiet, noncontroversial.”

A few weeks later, about 400 people received an unsigned letter directing them to write the Department of Economic Development in support of Shintech. The letter blamed the opposition on a “negative few” and “radical national environmental” groups. The writer suggested that residents “copy this letter and share it with friends.” The letter was eventually traced back to Hymal’s office because of a metered mail stamp. The 400 people who received the letter were people on a job waiting list.

“The history of this letter is very disturbing,” says Mary Lee Orr of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, a statewide group that, on behalf of the St. James Citizens, has filed an ethics complaint with the State Ethics Commission against the Parish president’s office. “It is hard to believe that taxpayers’ money can be used to support a particular position in the permit process. How can a Parish president’s office use taxpayers’ money to directly tell citizens to write letters of support for Shintech to the assistant secretary of DEA, while local, state, and federal permitting processes were ongoing?” she says.

Shintech recently contributed $5,000 to the reelection campaign of Mike Foster, governor of Louisiana. A Baton Rouge public relations firm hired by Shintech, Harris, Deveille and Associates, contributed another $5,000. The firm also contributed more than $2,000 in in-kind contributions.

Harris, Deville and Associates have widely distributed a study by a researchers at Louisiana State University which dismisses the idea of the risk of cancer as a result of Shintech emissions. According to the authors of the study, the cancers that do occur in the area are attributed to smoking and diet.

But three epidemiologists who reviewed the studies question the findings. First, they say the author of the report combined small parishes like St. James with large cities like Baton Rouge and New Orleans, which had the effect of masking any excess cancers that might be occurring in places like Convent. “These analyses have little sensitivity to the research questions about cancer excess which might be associated with environmental contamination in communities along the Mississippi,” writes Dr. Ted Schettler, a physician in Boston and author of Generations at Risk: How Environmental Toxins May Be Affecting Reproductive Health in Massachusetts.

“While the focus might have been on communities along the river, in these analyses the ‘river parishes’ are combined with Baton Rouge, which must dominate it statistically,” he continues.

Schettler suggests that to find excess cancers, it might be more useful to focus on smaller areas, like census tracts. Another problem, says Steve Wing, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is that the study focuses only on cancer. Exposure to PVC, Wing says, has been shown to cause other types of diseases as well.

Jobs. That is how state and local officials explain their support for the Shintech facility. The plant is supposed to provide 165 permanent jobs to local residents. Plus, according to a company spokesman, it will provide millions of dollars in revenue to the local economy.

But Shintech is receiving more than it will give, says Dan Mills, research director of the Louisiana Citizens for Tax Justice. Mills points out that like most industries in Louisiana, Shintech got the standard industrial package: a ten year property tax exemption which saves the company $94.5 million. The state has also designated the area where the plant plans to build as an enterprise zone. Enterprise zones are created in economically depressed areas to help alleviate poverty.

The rebate adds up to $35 million, and Shintech also gets a corporate income tax credit of $2,500 for each new job created. For the 165 jobs they will create, the company should receive $412,500. The savings to the plant will total $129.9 million. Over the same period, St. James Parish as a whole gets $18 million dollars. The black communities nearest the plant get more pollution.

Despite promises from Shintech and the local government — good jobs which pay as much as $40,000 a year — it’s doubtful that residents in an area, many of whom do not have high school diplomas, will be hired at the plant.

As Pat Melancon points out, the industry that is already present has not brought much economic development despite the industrial packages. “In my life I’ve seen five petrochemical companies come into Convent,” she says. “ I have seen businesses close down and the area become more depressed as these industries have come in. We haven’t seen any economic development. We’ve seen the opposite.”

A study by Paul Templet, former head of the Department of Environmental Quality, confirms Melancon’s concern. The study found that for all the incentives given to industry, these industries often provide more pollution than jobs.

But such bargains aren’t usually for Southern states like Louisiana. “In the South, ‘Everything is for sale,’” says Bob Hall, author of the Green Index, a ranking of the nation’s environmental health. For Hall and other critics of the South’s industrial policies, “everything” includes cheap land, cheap resources, and even cheap lives, especially those of minorities.

A recent ad in the Wall Street Journal seems to bolster this argument. The ad shows a man in a suit bent over backwards. “What has Louisiana done for business lately?” the ad asks, while touting the state passage of tort reform legislation and current governor Mike Foster’s background as a businessman.

Willie Fontenot, who runs Citizens Access Unit at the State Attorney General Office, says that many members of the state and local government see it as their job to help industry. “Most elected officials don’t see a conflict between community concerns and business,” says Fontenot.

Over 100 years ago, emancipated slaves came to the coast of the Mississippi River to escape slavery. Here they built homes, schools, and houses of worship. Here they hoped to secure economic and social independence from their former masters. Today they are fighting to secure emancipation of another kind.

The experiences of black communities in Convent are not unique. The town is one of many areas in the Gulf Region fighting the expansion of plants like Shintech, which have spread like cancer along the Mississippi River. In the past few years, there have been more than 14 expansions of PVC plants, most in low income and minority communities in the South.

The health and economic impact is untold. Many of these companies have polluted the air and fouled the water while promising economic benefits that never materialize. For the industry, it’s about market shares. They use their enormous economic and political clout to buy scientists, politicians, and public relations firms which craft crisis communication plans to counter the activities of communities and groups struggling for the most basic of rights: clean air and clean water.

For the communities, it’s about survival. In the end, communities in Convent could go the way of their neighbors down the Mississippi River. Towns like Sunrise, Revelltown, and Morrisonville no longer exist. Contaminated and bought out by Dow, Georgia Gulf, and Polacid Oil, as well as other companies, these communities, once safe havens for ex-slaves, are now toxic ghost towns.

Years ago, Louisiana struck a Faustian deal with the chemical industry. Today, black residents are paying the price with their health, their communities, and their very history.

A former resident of Morrisville summed up the experience: “They moved outwards slowly. . . . They weren’t always this close. But before you realize it, they were building right outside your door.

“Suddenly, every blade of grass is important to me. My husband planted hose pine trees in the year. You have to live another lifetime to get all this back.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.