This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Being charged with a capital crime is surely bad news anywhere, but there’s no place worse than Texas.

After the state Board of Pardons and Paroles turned down Karla Faye Tucker’s petition for clemency last February, she became the 146th person executed by Texas since the Supreme Court voted to reinstate the death penalty in 1976. Texas is also a trendsetter when it comes to killing the mentally retarded and children.

Texas, though, merely reflects what is true nationwide. The chance that a person charged with a capital crime will live or die depends enormously on race, social class — and perhaps most importantly, where the crime was committed. In calling for a moratorium on the death penalty last year, the American Bar Association said, “Today, administration of the death penalty, far from being fair and consistent, is instead a haphazard maze of unfair practices with no internal consistency.”

But Texas is still in a league of its own and the situation there is growing worse. Of the 146 people executed in the state since the death penalty was reinstated, 37 were killed in 1997 alone.

Racism plays a huge role in determining who dies. In one glaring example, Texas law enforcement authorities picked Clarence Lee Brandley, who is black, from among many suspects in a circumstantial case of rape and murder of a white woman. As authorities told Brandley — convicted but released in 1989 after being exonerated — “You’re the nigger, so you’re elected.”

Dallas has sent dozens of people to death row, but never for killing an African-American. Harris County (Houston) alone is home to 40 percent of all African-Americans in Texas on death row. Blacks make up only 20 percent of the county’s population but about two-thirds of its death row inmates.

Texas also boasts a number of mad dog district attorneys. In Dallas, the DA’s office prepared a manual for new prosecutors, used in the early 1990s, which said: “You are not looking for a fair juror, but rather a strong, biased, and sometimes hypocritical individual who believes that defendants are different from them in kind, rather than degree. . . . You are not looking for any member of a minority group which may subject him to suppression — they almost always empathize with the accused. . . . Minority races almost always empathize with the defendant.”

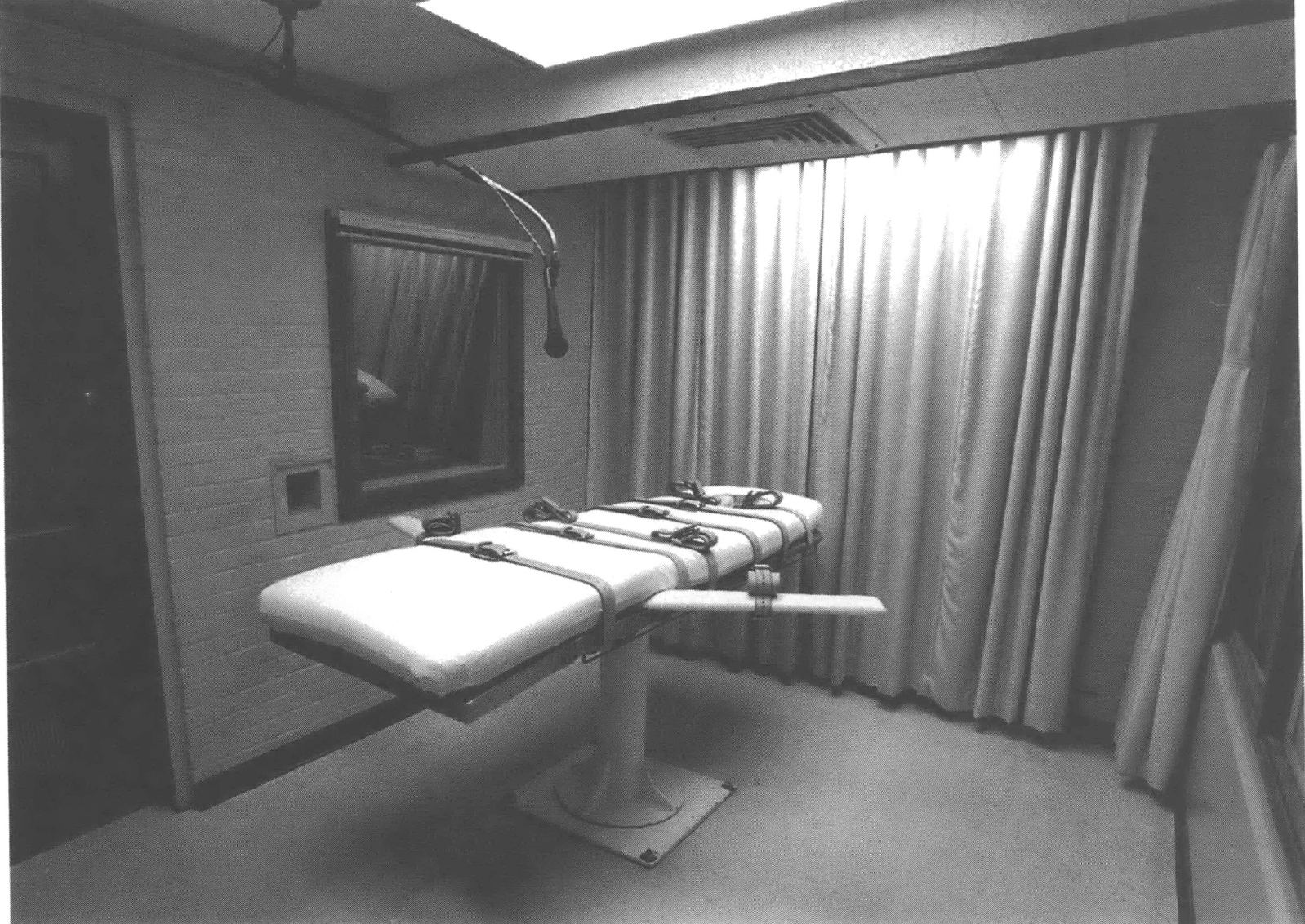

The city of Houston has executed more people since the re-imposition of the death penalty than any other state — except, of course, Texas. The Texas Observer recently dubbed Huntsville prison near Houston, where Karla Faye Tucker was executed, “the most active human abattoir in North America.”

The man most responsible for this dubious distinction is Johnny Holmes, who has headed the local DA’s office since 1979. Holmes hangs a sign in his office’s death penalty unit that reads, “The Silver Needle Society,” which contains a list of all the people killed by lethal injection in the county. Holmes’s office also reportedly throws champagne parties on the night of scheduled executions.

Texas DAs are exceeded in their zeal for the death penalty only by Texas judges. The most famous case is that of Harris County District Judge William Harmon. During the 1991 trial of Carl Wayne Buntion, Harmon told the defendant that he was “doing God’s work” to see that he was executed. According to a law review article by Brent Newton, “Harmon taped a photograph of the ‘hanging saloon’ of the infamous Texas hanging judge Roy Bean on the front of his judicial bench, in full view of prospective jurors. Harmon superimposed his own name over the name Judge Roy Bean that appeared on the saloon, undoubtedly conveying the obvious.”

Harmon also laughed at one of Buntion’s character witnesses and attacked an appeals court as “liberal bastards” and “idiots” after it ruled that he must allow the jury to consider mitigating evidence.

In a 1994 case, the defense requested that a number of death row inmates be brought to the courthouse. “Could we arrange to blow up the bus on the way down here?” Harmon asked.

Another reason Texas kills so many people is the abysmal quality of many of the court-appointed attorneys. Attorneys in Texas have been drunk during trial (one even had to file an appellate brief from the drunk tank), had affairs with the wives of defendants, and have been known to not raise a single objection during an entire trial. In all these cases, appeals courts have ruled that the defendants were provided with competent defense.

In three death penalty cases in Houston, defense attorneys fell asleep during trial. (“This gives new meaning to the term ‘dream team,” says Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights.) The trial judge refused to dismiss the case of George McFarland, convicted of a robbery-killing, by saying that the state had fulfilled its obligation of providing McFarland with counsel and “the Constitution doesn’t say the lawyer has to be awake.” An appeals court in Texas upheld the death sentence on McFarland and the Supreme Court refused to review the case.

Attorney Joe Frank Cannon has represented ten men sentenced to death. “Represent” here is a generous description. In the case of Calvin Burdine, the court clerk testified that Cannon “was asleep on several occasions on several days over the course of the proceedings.” Cannon’s entire file on the case consisted of three pages of notes. (The prosecutor in that case urged the jury to choose death over life in prison because Burdine was homosexual. “We all know what goes on inside of prisons, so sending him there would be like sending him to a party,” he said.)

During the past eight years, only the United States, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, and Yemen have executed children (those who were under 18 at the time of the crime). Texas is the leader in the practice of killing children. Johnny Frank Garrett was executed in 1992 for the rape-murder of a Catholic nun, committed when he was 17. As a child, Garrett was beaten by a series of stepfathers and was once seated on a hot stove because he would not stop crying. He was sodomized by a number of adults and forced to perform pornographic acts (including having sex with a dog) on film.

Garrett suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and while on Death Row regularly conversed with a dead aunt. Karla Faye Tucker got two abstentions from the Texas Boards of Pardons and Parole; Garrett, executed in 1992, was shut out 17-0.

Joseph John Cannon sits on death row in Texas for a crime he committed as a teenager. He suffered serious head injuries after being hit by a truck when he was four and subsequently spent years in an orphanage. Between the ages of seven and seventeen, Cannon was sexually abused regularly by his stepfather and grandfather. At the age of fifteen he tried to kill himself by drinking insecticide. None of this information was presented to the jury in Cannon’s case.

How to account for the singularity of Texas? We talked to Richard A. Ellis, an attorney based in San Francisco who handles death penalty appeals in states including California and Texas. He underlines the coincidence in Texas of two lethal traditions, namely Southern racism and hang ’em high frontier justice.

Though Ellis stressed that there are dedicated lawyers of high quality in Texas, such as those working in the Texas Resource Center (which, like other such appeals projects across the country, lost its federal funding in 1995), he agrees that the general level of legal representation in Texas is awful. “I’ve seen incredibly slipshod work there. A man on Death Row just sent me his state habeas appeal, which he saw as a ticket to lethal injection and he was right. It is 50 large-type pages of illiterate nonsense, and this from an attorney who lectures on habeas!”

Ellis says the state habeas appeal these days is often a convicted person’s only chance at reprieve, in which fact-driven issues (such as ineffective counsel) impinging on a person’s constitutional right to fair trial can be raised. “In California, an appeals attorney can regard $35,000 as a reasonable (state-provided) opening budget, with the whole budget going to $150,000 and up. I just had a Texas case where I needed an expert witness, who could cost around $15,000. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals gave me a total budget for the entire appeal of $5,000.”

Of course, appeals face desperately long odds in all states. But in California, which actually has more people on Death Row than Texas — 477 to 428 — there are far more lawyers and investigators working to keep their clients alive. As a result, California has only executed four people since the death penalty was reinstated.

Texas is the only state where a judge or state attorney general can set an execution date long before the appeals process has been exhausted. Ellis noted one case where a condemned man saw his federal appeal go through district court, circuit court, and the U.S. Supreme Court in less than a month, with the last two appeals occurring on the day of his execution. The Supreme Court finally granted a stay 45 minutes after the scheduled hour of his death (authorities were good enough to delay the injection while they waited for a ruling to come down).

California is as eager as Texas to kill people. But there’s a large and active legal opposition, plus the all-important presence of money. As Ellis points out, “In California, I can have a co-counsel. In Texas, I’m the whole team. Texas is an unbelievable death machine.”

“A Brazen Racial Animus”

Crime and Capital Punishment in the South

By Jeffrey St. Claire

To be sure, Texas faces stiff competition in laying claim to the title of Death State. In Georgia, all 46 state district attorneys — who alone are charged with deciding whether to seek the death penalty — are white, while 40 percent of those sentenced to death since 1976 are black. No white person has ever been executed for the murder of a black person in Georgia, nor has the death penalty ever been sought in such a case. Of the 12 blacks executed in Georgia since 1983, six were sentenced in cases where prosecutors had succeeded in removing all potential black jurors.

Nor does the warden of Georgia’s state prison system, a mortician, inspire great confidence. After being appointed, he declared that many prisoners in the state are not fit to kill. He later led a raid on one penitentiary in which, according to 18 employees, prisoners who were handcuffed or otherwise restrained were beaten.

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that people sentenced to death are not entitled to representation in post-conviction hearings. Georgia was the first state to take advantage of this decision when in 1996, it ordered Exzanavious Gibson, a man with an IQ of 80, to defend himself.

Eddie Lee Ross, a black man, was defended by a court-appointed attorney who served as the Imperial Wizard of the KKK for 50 years. Ross’s lawyer fell asleep during the trial, failed to make any objections, filed no pre-trial motions, and missed numerous court dates. Ross got the death penalty. James Messner, who was brain-damaged, was electrocuted on July 28, 1988, after his own attorney suggested in closing that the death penalty might, in fact, be the appropriate sentence.

In the case of William Hance, a black man, the jury was deadlocked at 11-1 for death, with the lone hold-out being a woman named Ms. Daniels, the only black person on the panel. Death sentences must be unanimous in Georgia, so the other jurors began pressuring Daniels. One said, “We need to get it over with because tomorrow’s Mother’s Day.” Daniels refused to budge, but the foreman sent the judge a note saying the jury had voted for death. Despite an affidavit from Daniels, Hance went to the electric chair in 1994.

Virginia executes more people than any other state but Texas — 42 since the death penalty was reinstated. The situation in the town of Danville, the last capital of the Confederacy, is instructive in regard to how the death penalty is imposed. According to the Richmond Times-Dispatch, since the town was incorporated in 1890, every person executed in the town has been African-American.

Danville’s chief prosecutor, William Fuller III, has sent seven men, all black, to Death Row. That’s one fewer than the number of men condemned to Death Row in Richmond, a city with a population almost four times higher.

Fuller has charged eighteen people in Danville with capital murder, 16 blacks and two whites. He sought the death penalty for eight of the African-Americans and none of the whites. “Danville’s criminal justice system is an unconstitutional embarrassment,” lawyers for Ronald Watkins, one of the condemned, wrote in a pending appeal to a federal court. “The brazen racial animus that fuels the death penalty machine in Danville should be acknowledged and neutralized.”

In Alabama, the maximum fee allowed to a court-appointed attorney is $2,000. “I once defended a capital case [in Alabama] and was paid so little that I could have gone to McDonald’s and flipped hamburgers and made more than I made defending someone whose life was at stake,” says Stephen Bright.

In South Carolina, the state attorney general campaigned on a platform that called for replacing the electric chair with an electric sofa in order to speed the pace of executions.

Tags

Ken Silverstein

Ken Silverstein and Jeffrey St. Claire write for the investigative newsletter CounterPunch. For this report, the authors are grateful to Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta and two death penalty lawyers in Texas, David Dow and Brent Newton, who provided the authors with much of the information in this article. (1998)

Jeffrey St. Claire

Ken Silverstein and Jeffrey St. Claire write for the investigative newsletter CounterPunch. For this report, the authors are grateful to Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta and two death penalty lawyers in Texas, David Dow and Brent Newton, who provided the authors with much of the information in this article. (1998)