This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

Globalization is no longer a new term. Its use has become as common as any word. But the socio-economic and political dynamics it refers to are monumental indeed. There is no region or country in the world untouched by the current trends in global economic and political policy, and the U.S. South is no exception.

Workers and their communities are suffering the ill-effects of global corporate power, including low wages, poverty, instability, privatization, shifting capital, lean production, massive deregulation, unemployment, and massive corporate subsidies. The sovereignty of whole nation-states is under direct attack in this new global world order. This is the reality of globalization for people everywhere.

In this process of globalization, one does not have to look far to see how the South, along with the Southwest and Native American Territories, have come to resemble a Third World within the borders of the United States. As First Union National Bank writes in its latest Regional Economic Review, “In the increasingly global economy, the South’s international connections are becoming more important. The Southeast is far and away the leader in attracting investment from overseas, accounting for close to half of all new facilities built in the U.S. by foreign-owned firms during the 1990s. To many international investors, the Southeast possesses many of the same advantages found in the world’s newly industrializing countries without the risk.”

“The South’s economy ranks as the fourth largest in the world,” the report goes on to note, “and has grown an average of 6% a year since 1991. Wage rates, while rising, remain well below the U.S. average and productivity growth is stronger.”

This South’s rise to prominence in the international context is the result of a long history of struggle between the forces of change and those of reaction: slavery and slave rebellion; Jim Crow and freedom movements; industrialization and the repression of worker organizing. Thus, while the intensity of globalization in the last decades of the 20th century is spectacular, it is by no means new — and has not changed the neo-colonial status of the South’s people.

“Free Trade” and Global Empires

Religious crusades, the trade of commodities, and the journeys of refugees are all examples of events that have crossed geographical borders throughout history. The spread of Christianity in Europe from 476-1056, for example, was an early form of global empire-building, as was Spain and Portugal’s Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494 and creating a north-south Line of Demarcation to divide “discovered” lands around the world between the two powerful countries.

It was in the 1600s that global trade began to rise. As European rulers came to see that trade was as important as gold, they system known as mercantilism took hold.

Mercantilism rested on three key beliefs, which have shaped globalization to this day. First was the primacy of trade: the idea that a nation’s economic strength depended on exporting more goods than it imported. Second, leaders of the new system declared that more profit is made selling manufactured goods than raw materials. Lastly, the new powers argued that the state should play an active role in supporting economic activity through regulating commerce, and supporting industries such as shipbuilding needed for the new trade-based system.

The new system relied on the subjugation of millions of people. It required conquered colonies to supply raw materials to the mother country, as well as serve as markets for finished goods.

The system also needed slaves. Across the Americas, plantations were spreading to grow sugar, cotton, and tobacco, and they needed cheap labor to be productive. The global African slave trade began, coming to the South in 1619 with the first shipment of 20 Africans to Jamestown, Virginia.

Slavery and the plantation system may have been, in the words of Karl Marx, “primitive accumulation,” but the profits were enormous. As early as the 1680s, The Royal African Company transported an average of five thousand slaves a year. As DuBois describes, the web of “triangular trade” developed by Great Britain was a clear sign that a new global economy had arrived:

The Negroes were purchased with British manufactures and transported to the plantations. There they produced sugar, cotton, indigo, tobacco, and other products. The processing of these created new industries in England; while the needs of the Negroes and their owners provided a wider market for British industry, New England agriculture, and the Newfoundland fisheries.

King Cotton’s Global Reign

The global slavery system took root in the South with the rise of King Cotton. “Where cotton was king,” writes George Novack in America’s Revolutionary Heritage, “the whole economy fell under its sovereign sway. The price of land and the price of slaves were regulated by the price of cotton. A prime field hand was generally calculated to be worth the price of ten thousand pounds of cotton. If cotton was bringing twelve cents a pound, an able-bodied black was worth twelve hundred dollars on the slave market.”

By 1850 the cotton kingdom covered about 400,000 square miles stretching from South Carolina to San Antonio, Texas. Cotton constituted over half the total exports for the U.S. in 1850, and commerce, manufacturing, and banking in the North depended on the cotton/slave system.

As with all global systems before and since, the state actively protected and supported King Cotton. From 1820 to 1860, the cotton nobility controlled the president, the cabinet, both houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, the foreign service, and they dictated the major policies made in Washington.

Cotton was also a driving global force. It powered the industrial revolution: Cheap labor in the English textile mills and slavery on American plantations combined to enrich England, fueling their ability to reach further into India and Africa.

The harsh conditions of the slave system on which cotton depended have been well-documented. But little is said of slave resistance, which was crucial to slavery’s destruction. There were over 250 slave revolts from colonial times to the Civil War.

This resistance was also an early example of cross-border solidarity: as DuBois notes, uprisings elsewhere, such as the revolution in Haiti, “threatened the whole slave system of the West Indies and even of continental America.”

Finally, in the 1860s, the cotton slavocracy collapsed under the weight of a single crop economy. But what soon became clear is that the South — the supplier of raw material in the global cotton system — gained little from the profits reaped during cotton’s reign.

“Though the cotton, rice and sugar of the South sold for $119,400,000 in 1850, the total bank deposits of the region amounted to only some $20,000,000,” writes Novack. “Ten years later, when the value of the crops had increased to more than $200,000,000, less that $30,000,000 was deposited in the banks of the cotton and sugar belt.”

The source of wealth, but not the benefactor — this exploitive relationship, seen in many Third World countries, was to become a familiar pattern for the South as the slave economy gave way to 20th century globalization.

“Restructuring” and the New South

While the South languished under Jim Crow, a new world order was taking shape after World War II. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreements on Tariff and Trade (see “A Globalization Glossary,” page 57) all were being established to shore up the strength of the major economic powers.

Fearing the end of the war-time industrial boom, the Southern corporate leaders and politicians began looking worldwide to bring business to the region. With a formula of cheap labor, cheaper land and generous incentives, the region soon became a haven for foreign investment, which fueled the rise of the “New South” as a global player.

By the early 1970s, a period of global “restructuring” was underway. The U.S. economy began to experience a falling rate of profit, largely due to the rising strength of Europe and Japan.

At the same time, the world’s currencies became deregulated, beginning in earnest the corporate search for cheaper sources of labor and resources. The U.S., Europe, and Japan began to increase their loans of “foreign aid” to developing, “Third World” countries of the global South, through the World Bank and IMF. The conditions attached to those loans came from the “Washington Consensus,” a model of development based on the belief that deregulated, market economies were the only hope for poor countries.

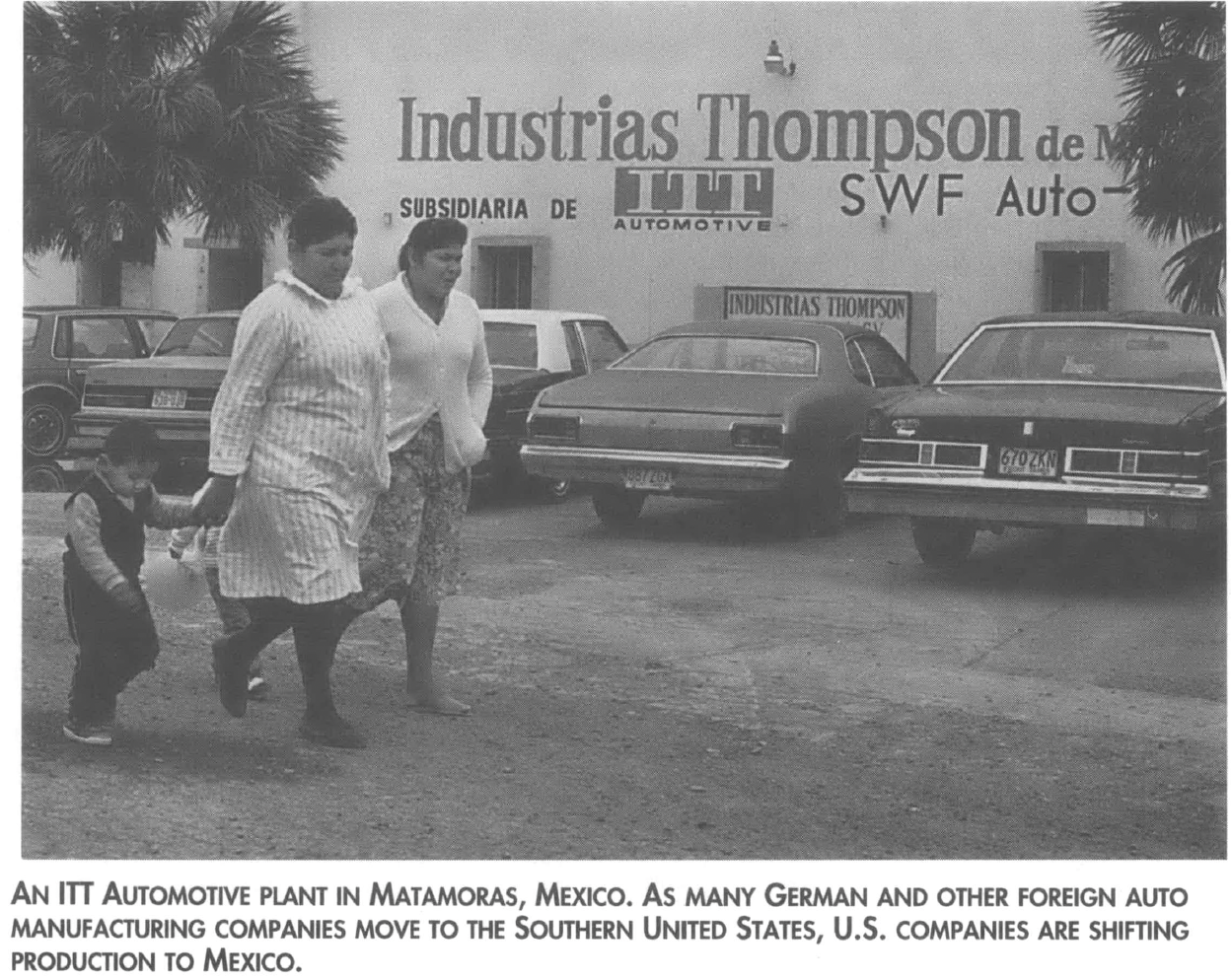

The impact was felt everywhere. Under the guise of doing whatever it took to win in the global marketplace, corporate America began demanding—and getting—concession after concession from American workers. Plants were played against each other; others shut down altogether and set up shop in non-union areas with more exploitable resources.

Runaway shops became increasingly common as business moved to the “sunbelt” — the Southeastern and Southwestern U.S. — and then on to Mexico and other nations. The impact was severe, especially for the African-American community: the resulting lack of stable blue-collar jobs is cited by some experts as a leading cause of the urban underclass.

The Global South Today

Globalization today is marked by new forms of corporate control over the economy, from new work systems and “labor/management cooperation” to privatization of public goods and services. These trends have not escaped their Southern context.

In the late 1980s, the U.S. South emerged as the top region in the country for privatization. The main form privatization has taken in the region has been in the form of contracting out. Nine southern states showed significant efforts to privatize public transportation. Water systems and social services are also targets of this policy.

The decline in federal aid to support public services coupled with the massive tax breaks and subsidies given to attract private industries to various states, have been key to underpinning the trends in the South toward privatization.

Moreover, the lack of unionization in the region weakens the ability of impoverished Southern workers and the U.S. national trade union movement as a whole to effectively combat the forces of globalization.

The South has always featured a conservative political climate, designed to limit union power in the region. Right-to-work laws have been especially crippling, forcing unions to represent nonmembers. In twelve Southern states, including the District of Columbia, there are roughly only 2.3 million dues-paying members, yet these same unions must represent over 2.7 million workers in their bargaining units. This is not only a drain on minimal resources, but also directly undermines the collective strength of local unions, giving undue advantage to the employer.

Political powerlessness for the African-American population in the South is also a feature of the Southern political climate, reinforced by international trends and policies of globalization. Majority Black congressional districts from North Carolina to Louisiana have been targeted for elimination in an increasingly conservative political climate.

Finally, the role of gender issues in the globalized economy is also reflected in the conditions of Southern working people. Black women bear the brunt of economic exploitation, suffering the lowest per capita income of any sector of the U.S. landscape. Forty-five percent of Southern black families are headed by single women, whose median income was only $12,000 in 1993.

As one astute analyst framed it in the excellent anthology Creating a New World Economy: “Global militarization, the environmental crisis, global inequality, U.S. economic decline, and corporate control over the economy illustrate the profound ways in which global and domestic problems interact and the ways in which the solutions to global problems depend on solutions to domestic ones and vice versa.

“In short, to solve the problems we face, we must think locally and globally at the same time if we are to act at all. This means that progressive analysis and discussion of the global economy is now more important than ever.”

Tags

Hasan Crockett

Dr. Hasan Crockett is professor of Political Science at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia and Director of the Brisbane Institute. (1998)

Dennis Orton

Dennis Orton is a former Senior Field Representative for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Associate Director of the Brisbane Institute: Southern Center for Labor Education and Organizing (SCLEO). (1998)

Ashaki M. Binta

Ashaki Binta is also a former Senior Field Representative of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Associate Director of the Brisbane Institute/Southern Center for Labor Education and Organizing (SCLEO). Additionally, she serves as Director of Organization for the Black Workers For Justice. (1998)