Ladybugs

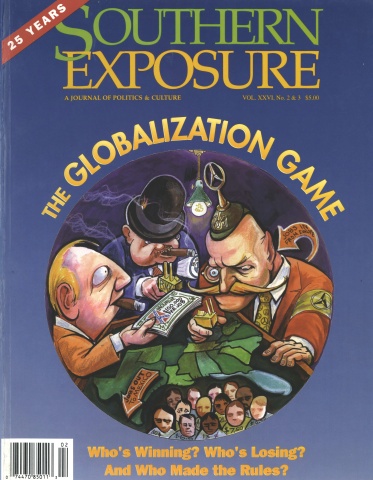

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

The South never seems to see the end of invaders. The newest intruder into Southern homes and gardens is the ladybug. Long a fondly regarded character of nursery rhymes, this red spotted beetle has become an unwelcome visitor.

“In the early 1990s there was a lady beetle population explosion,” says James Jarratt, Extension Entomologist at Mississippi State University in Starkville. “I’ve never heard complaints like that in my life. There were untold thousands of the lady beetles in peoples’ homes.”

The ladybug population explosion isn’t simply a natural occurrence. The South has always had several of its own varieties of lady beetles, but the new invader is a foreign import. Touted as an excellent non-chemical means of controlling aphids and other crop-destroying pests, the multicolored Asian lady beetle was imported from Japan and introduced into agricultural regions of Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The bugs did their job, successfully preying on the aphids that attack pecan trees throughout the Deep South. The trouble is, unlike native species that seek bark or leaves for protection in the winter, the Asian lady beetle likes rocks. And houses seem an awful lot like big rocks.

“They are attracted to the warm side of light colored houses,” says Jarratt. “They get in through cracks in the walls and overwinter in wall boards. When it warms up, they become active and hundreds will work their way into living spaces.” Once they’re indoors, he adds, ladybugs may cling to curtains or congregate around light fixtures. While they’re harmless, they can become an annoyance because of their sheer numbers. Jarratt says the creatures fall in people’s food while they’re cooking, secrete a staining blood if disturbed, and may create an odor, particularly if many of them die in the walls.

“They were a big hassle,” says Teresa Ingram, whose Louisville, Mississippi, home was invaded a few years ago. “They’d get inside and cover the ceiling so that I’d have to vacuum every day. It was just awful.”

The problem is so widespread that desperate computer users have started a chat room on the Internet dedicated to the ladybug invasion. “We have ladybugs swarming inside and out,” writes MW. “I have come home and just cried because there were so many.” Fellow chatters tell her they’re harmless but to try Raid, vacuuming, or calling a county extension agent to curtail an infestation. AM from Virginia asks, “This is our fourth year of ladybug infestation. Am I doomed from here on out to years of vacuuming? Does anyone have any truly helpful solutions?”

A small industry has grown around trying to find solutions to ladybug infestations, mainly through the use of pesticides. Agricultural extension specialists take a milder approach, telling concerned callers that lady beetles are beneficial and should be controlled by simply caulking crevices in houses to prevent their entry or, if they do invade, simply vacuuming them and releasing them outdoors.

But, as extension specialist Frank Wood in Guntersville, Alabama, found out, the mild approach may not satisfy an irate caller. “A woman called me and said she didn’t care how beneficial they were,” says Wood. “She had company coming for Thanksgiving dinner and she wanted those things out of her house.”

At least one USDA representative now says that this attempt to control the forces of nature may have gotten out of hand. “It has become a very sensitive issue,” says Louis Teddars, an entomologist with the USDA Fruit and Nut Station in Byron, Georgia, who released the ladybugs there in 1984. “People are really upset and I’m sorry.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)