This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

Mendenhall, Mississippi, December 14, 1963: Most everyone is here. And not just from Mendenhall and Magee, the two rivalrous siblings anchoring the northern and southern ends of Simpson County, but from the outlying villages: Pinola and Sanatorium and D’Lo and Braxton and Harrisville and Merit. And they’ve come despite the terrible weather: it didn’t merely sleet in the middle of the night; it poured what seemed like fully formed sheets of ice.

They have come to this strange, sprawling mecca of corrugated metal and brick plunked down on U.S. Highway 49, smack between Mendenhall and Magee in the piney woods of south central Mississippi, to celebrate the grand opening of their county’s first industrial employer, Universal Manufacturing Company, a maker of ballasts for fluorescent lights. (The ballast regulates the flow of current in the lamp.)

Following the invocation, the festivities commenced with the playing of the National Anthem by the combined high school bands of Mendenhall and Magee — itself no small feat of diplomacy — and ended with box lunches and guided tours of the shiny plant. In between there was all manner of speechifying and bow-taking by local politicians, the plant managers, and state economic-development officials.

Also appearing was Governor-elect Paul B. Johnson, an ardent segregationist who was swept into office the previous month on a wave of support from his notorious predecessor, Ross Barnett. It was Barnett himself who had led the negotiations with Universal’s founder and president, Archie Sergy. And it was Barnett and Sergy who would jointly cut the ceremonial ribbon.

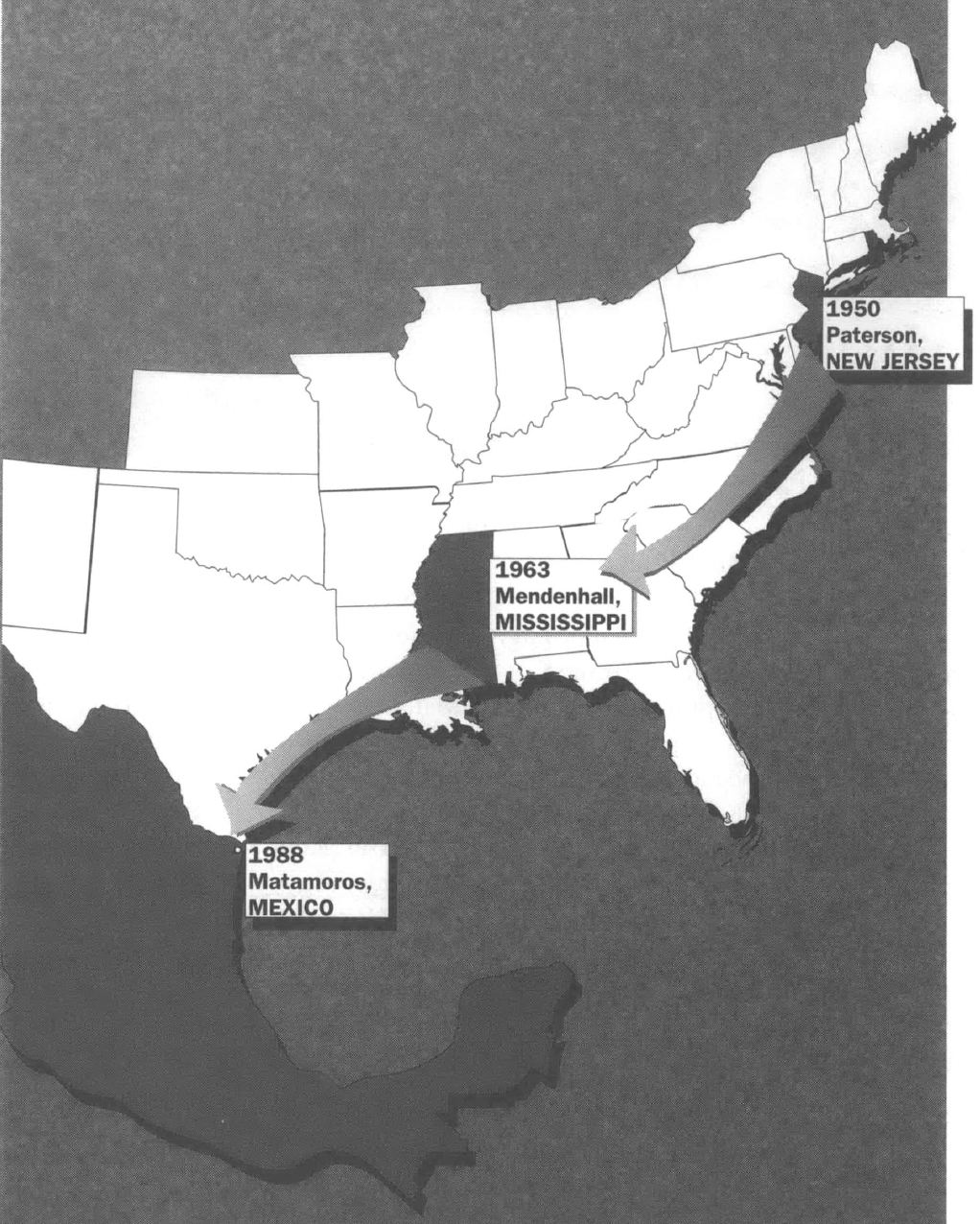

Sergy had flown in from headquarters in Paterson, New Jersey, where his flagship plant, opened in 1950, was still in operation. But he’d recently had union problems there — the incumbent Teamsters had beat back the IUE, the International Union of Electrical Workers, in a bloody battle for control. Sergy, a 48-year-old Paterson native, wanted an ancillary plant in the union-free, low-wage, low-tax South.

In Mississippi, courtesy of the state’s hospitable Balance Agriculture With Industry (BAWI) program and the county’s million-dollar bond issue, Sergy found what he was looking for. He predicted a “long and prosperous relationship between Universal and Simpson County.”

Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, June 10, 1988: It is a blindingly blue, hot and humid morning, and Hector J. Romeu, Jr. is one frantic man, as harried as Chaplin’s Little Tramp. Matamoros is a rapidly growing border city across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas. Romeu, like the border region itself, straddles both countries; he was born in Mexico and schooled in the U.S.

Romeu handles sales and public relations for the Finsa Group, a principal developer of industrial parks along the Mexican border. Its original park, less than a ten-minute drive from the International Bridge across the Rio Grande, occupies five hundred acres on what used to be farmland on the west side of Matamoros. Romeu has been chasing his tail for weeks, tending to the innumerable details of staging today’s gala: It’s the Grand Opening of the first MagneTek Universal Manufacturing plant here.

Archie Sergy no longer owns the company. He sold it shortly after cutting the ribbon in Mendenhall and it has since changed hands three more times, most recently to MagneTek, Inc., a public company based in Los Angeles. MagneTek was formed in 1986 by a Los Angeles art collector and leveraged-buyout specialist, Andrew G. Galef. Galef’s investment advisor was Michael Milken, whose firm underwrote the deal with “junk bonds.” (Milken later pleaded guilty to six counts of securities fraud and spent two years in prison.)

Hector Romeu’s two years of gut-grinding work — from recruiting MagneTek to shepherding it through site selection and groundbreaking the previous March, to the manufacture of the first ballasts — all of that pays off today. He has been rewarded with a splendid morning, and the MagneTek honchos, in from headquarters in Los Angeles, are delighted with their gleaming plant and the enthusiastic welcome Romeu has orchestrated.

There are city and state officials and union leaders on hand to meet and greet the American executives, as well as a reporter and photographer from El Bravo, the Matamoros daily with long and deep ties to Romeu’s employer, the powerful Arguelles family. And Romeu even has thought to outfit the visiting execs in natty going-native panama hats emblazoned with MagneTek’s royal blue capital-M “power” logo.

The plant manager, an affable Arkansan named Chuck Peeples, leads the officials on a tour of the plant, the first of a projected five interconnected facilities to open on site. (A sixth would open in 1994 on a lot across the industrial park.) The equipment they stroll by is operated by a young, almost entirely female workforce. These women, primarily in their teens and twenties, have come north in search of work and a better future than the bleakness promised in the jobless farming towns of the interior.

After the ribbon is sheared and the plant inspected, the entourage of revelers shuttle over to American soil for a cocktail party at Rancho Viejo, a country club and condominium development a few miles north of Brownsville. There in the Casa Grande room MagneTek executives rub elbows with officials from Finsa, with politicians and chamber of commerce officials from both sides, and with fellow American manufacturers along the border, members of the Brownsville-Matamoros Maquiladora Association.

Drinks flow from the open bar, tuxedo-clad waiters serve fresh shrimp, taquitos, cheeses and fresh fruit. Hector Romeu, his work completed, moves serenely among the guests, nodding, touching an elbow here, slapping a back there, introducing MagneTek officials to their counterparts at General Motors and to others of his 15 American corporate clients in the industrial park.

The story of these ribbon cuttings, a quarter-century, 800 miles, and an international border apart, is that of North American labor and capital during the latter half of the twentieth century and the dawn of the next. Indeed, the story of Universal Manufacturing — its employees, its owners, its communities — is a clear prism through which to view a much larger tale: that of the global economy. But the story of Universal doesn’t begin in Mendenhall, and it will not end in Matamoros. It begins, appropriately enough, in the cradle of American industry: Paterson, New Jersey.

Paterson was founded on the sixteenth anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1792, not as a municipality but as a business: the home of the country’s first industrial corporation, the Society for Useful Manufactures. The Society’s guiding light was Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Treasury Secretary, who envisioned Paterson as a great National Manufactory.

The plan failed, but Paterson has always been a magnet for dreamers and schemers, an entrepreneur’s city. In 1950, when Archie Sergy opened his plant, Paterson was brimming with factories small and large — from textiles (it was once hailed as “Silk City”) to machine shops to electrical components. The city’s postwar boom attracted many migrants, including a young woman from rural, central Virginia named Mollie Brown — “Dimples” to the folks back home in Cartersville.

Richmond, Virginia, November 1950: Rolling into Broad Street Station on the daily northbound run, the conductor of the Silver Meteor does not bother to stop the train. Richmond is not a principal destination for the Meteor, the queen of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad’s Florida to New York whistle-stoppers, and so the depot merits the train’s slowing only enough for passengers to disembark and for new passengers to hop on.

At a few minutes before two on a cold, pitch-black morning, a father and his nineteen-year-old daughter wait anxiously on the platform of the ornate World War I-era station. Mollie Brown is headed to Penn Station in Newark, New Jersey, to meet her fiancé, Sam James, who would take her home, to Paterson, to her new life. She was dressed in her finest: a new navy blue suit. She carried nearly everything she owned in a half-dozen sky blue suitcases her father had given Mollie for the trip.

Mollie is traveling alone, but the “colored” train cars of the Silver Meteor, and indeed those of the other great northbound coaches — the Champion, the Florida Sunbeam, the Silver Comet — are full of Mollie Browns: black southerners crossing the Mason-Dixon Line, heading for the promised land. Those from Mississippi and Alabama and Arkansas commonly headed for Chicago or Detroit; Texans and Louisianans went west; Georgians, Carolinians, and Virginians usually stayed on the Eastern Seaboard, migrating to Washington, Philadelphia, New York. Or to smaller industrial cities such as Camden, New Jersey, and Newark and Paterson.

There were so many places to work,” Mollie recalls of her early days in Paterson. “You’d just catch the bus and go from factory to factory and see who was hiring.” Among her stops was a low-slung cement building in Bunker Hill, a newly industrializing neighborhood near the Fair Lawn bridge in northeast Paterson. The sign out front said UNIVERSAL MANUFACTURING COMPANY. Mollie knew no one there, nor had she heard of the company or understood exactly what it manufactured. “Something about a part for fluorescent lights,” she told her husband that night.

Mendenhall, May 1961: It is graduation day at New Hymn School, the black school in rural Simpson County, and Dorothy Black is sitting in the auditorium, mulling what to do with her life. She’d grown up on sixty acres in the country; her parents farmed cotton and corn and some cucumbers. The family also raised hogs and dairy cows. “Even if it was nothing but a biscuit every day, we never went hungry,” Dorothy says.

Her parents had been denied a formal education; neither had made it past eighth grade. But they saw to it — “demanded” — that Dorothy and her five sisters — she was the third oldest — finish high school. And even though Dorothy’s parents needed her in the fields, keeping her and her sisters out of school every September and October to pick cotton, Dorothy always managed to attend school when the books (handed down from the rural white school) were distributed, and always kept up with her studies.

On this day her hard work is recognized: she is honored as class salutatorian. There would be no immediate payoff for her academic prowess. In the fall of the year she married a classmate, Louis Carter, who had entered the Army. Louis was stationed in Kansas, where they would live until the following summer. They returned home for a month, could find no work, and decided to follow the path of most of their classmates: they moved up North. They headed to Indianapolis, where job opportunities were little better. In the spring of 1963, they again came home, moving in with Louis’s parents. Louis found occasional work cutting pulpwood; Dorothy went to work as a maid in Jackson, some thirty-five miles from home. She earned three dollars a day, one of which went to her carpool driver.

The earlier report that nearly everyone in Simpson County attended the plant’s grand opening was lifted from coverage in the county’s two weekly newspapers. What the papers meant was that nearly every white person attended. No blacks were there, nor were any, with the exception of a single janitor, employed at Universal. That would not change until after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — and then not immediately.

Louis Carter was among the first blacks to seek a job after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the law. He and a friend went to the plant gate, where a guard matter-of-factly informed them the company would not be taking their applications: “We don’t hire niggers here.” (It should be noted, however, that once the plant integrated, the manager, an emigre from Paterson, took a courageous and principled stand against white resistance.)

By mid-1965, word had filtered down of a change in Universal’s hiring policy. As Dorothy’s father reported to her, “The government is making them hire black folks so you need to go up there.” She was hired the day she applied. Like Mollie James, she had “no idea” what a ballast was. She did know she would earn $1.10 an hour, which was considerably better than the two dollars a day she took home as a maid.

Ciudad del Maiz, San Luis Potosi, Mexico, April 1991. Her funds were dwindling fast. She’d had the equivalent of about 90 dollars to begin with, and now that she’d paid a man 20 to taxi her the hour from her mountain village — a place of clean and clear air, almost surrealistically bright light, and desperate poverty — to the bus station in town, and now that she’d bought a couple of tamales from a sidewalk vendor and a one-way ticket on the nightly bus to Matamoros for 30 dollars, Balbina Duque Granados was down to less than 40 dollars.

Although the bus would not depart until 9:15 this evening, Balbina’s driver had needed to make the trip early in the morning, so she spent the day keeping vigil over her three bags in the bus station, a green-and-white cement building spared from full-onset drab by the presence of numerous framed color photographs of luxury coaches.

Balbina was leaving for the border, 400 miles northward, to work as a caretaker for an elderly couple with ties to her village. She was torn about going, especially about having to leave her 18-month-old son behind with her mother. “If there were work here,” Balbina said in Spanish during a visit home not long ago, “everyone would stay.”

But there was no work. As a grocer in town explained: “You really don’t have a choice. One girl will come home in new clothes and three or four girls will be impressed enough to follow her — to Matamoros or wherever.” They followed one another into the maquiladoras, the largely American-owned plants that have sprouted along the border since the free-trade zone there was established in 1965, the year Dorothy Carter started working at Universal.

Three decades later, it was at Universal’s corporate successor, MagneTek, that Balbina wound up after the caretaking job didn’t pan out, and after a failed marriage and a series of odd jobs, including a housekeeping stint at a motel that rented rooms by the hour. The factory job was Balbina’s “answered prayer.” It was difficult work, coil-winding, repetitive and tiring and mind-numbing, but it was a job she was thrilled to have. And although Balbina didn’t know it, it wasn’t just any job — it was a job once held by both Mollie James and Dorothy Carter.

Paterson, June 30, 1989: It is three o’clock on a warm afternoon, and the second of the two washup bells has rung for the final time. Mollie James has been here, on the assembly line at Universal Manufacturing, since 1955. She was the first female union steward, the first woman to run a stamping machine, the first to laminate steel. And now, after thirty-four years on the line — nearly two-thirds of her life — she’s the last to go.

Her wide shoulders are hunched over the sink as she rinses her hands with industrial soap alongside the others. She is a big-boned woman of fifty-nine, with a handsome, animated face framed by oversize glasses.

Rumors of the plant closing circulated freely for well over a year. There already had been several rounds of layoffs. And even though the company had promised employees as recently as six months ago that the plant would not close altogether, few believed it.

It was around then, in fact, that movers had begun pulling up much of the plant’s massive machinery, much of which was bolted to the cement floor when the plant opened in 1950. By this early summer afternoon four decades later, vast stretches of the floor were uninhabited, marred by huge potholes where once had been signs of American industrial might.

“The movers came at night, sometimes just taking one piece at a time,” Mollie recalls. “We’d come in in the mornings and there’d be another hole in the floor.”

There were no valediction speeches from company or union officials, no farewell luncheon, no pomp of any sort. A week earlier, the workers themselves held a dinner at Lunello’s, an Italian eatery on Union Boulevard. They’d kicked in fifteen dollars apiece and celebrated their long years together at Universal. Many of these people were more than coworkers; they were friends on whom Mollie has come to depend as she would a member of the extended family. They ate together at work, attended weddings, baptisms, parties, funerals together.

On this afternoon, though Mollie knows many of her co-workers better than she knows some of her relatives — knows their mannerisms, ways of speech, strengths, flaws — on this afternoon their voices blend, their faces blur. The decades together on the line have done that: bound together the most varied of people. Black and white Americans. Dominicans. Russians. Italians. Indians. Puerto Ricans. Peruvians. They came to work for Universal — and stayed — because of the good wages and benefits their union had negotiated, and because the job seemed a secure one — a job they could raise a family on, buy a house, a car, borrow money against, count on for the future.

Matamoros, June 10, 1988: It was the future to which Anthony J. Pucillo, the company’s executive vice president of ballasts and transformers, directed his remarks during the Grand Opening ceremonies. Pucillo applauded the way labor and management worked together to open the plant — the first ballasts came off the line here two months earlier, in April. “In order to be able to successfully compete in world markets and create jobs,” Pucillo said, “one has to rely on this kind of team. Here in Matamoros, people have a vision for the future; if we can make quality products at competitive prices, the company grows. If MagneTek grows, we all grow.”

If Pucillo’s vision was not original, it remained compelling: that labor would prosper alongside capital. It was the very notion that had pulled a teen-age Mollie James out of her native rural central Virginia four decades earlier, had convinced Dorothy and Louis Carter to remain in Simpson County, would shortly draw the young and frightened Balbina Duque to the teeming border from her home in the placid high-desert of central Mexico.

September 1998: Despite attending a computer-training course, Mollie James has never again found work. She lives on Social Security and rental income from the three-family house she owns. She will turn 67 in October and hopes soon to return home to Virginia. Dorothy Carter, 55, spent 20 years at Universal, working her way up to a management position. She left the company in 1985 to start a bakery. The bakery has since closed, and Dorothy works as a pharmacy clerk. She and Louis, who in 1973 became the local union’s first black president, are divorced. Balbina Duque, 27, still works for MagneTek. She earns $1.45 an hour. Even with overtime, the wages do not cover basic expenses for herself and her three children. Along with her sister and her sister’s two children, they share a two-room cement-block house. The house has neither indoor plumbing or heat. It is located in the neighborhood of Vista Hermosa — Beautiful View — just beyond the rear fence of the MagneTek plant.

The Mississippi plant will close this month. The company is reportedly moving those operations not to Matamoros, but 45 miles or so west to the border city of Reynosa, where the unions are weaker and where the prevailing wage is a few pesos lower. Hector Romeu is scouting sites there.

Tags

William M. Adler

William M. Adler lives in Austin, Texas. He is at work on a book about Universal Manufacturing. Research support for portions of this article were provided by the Dick Goldensohn Fund and by Carol Bernstein Ferry. Spanish translation by Christina Elena Lowery. (1998)