Going for Broke

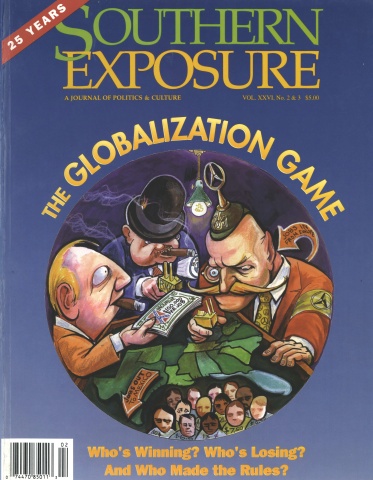

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

The drive down into South Carolina on Interstate 85 may be four-lane highway, but on a crisp October afternoon, the ride is rich with the sights of the South. The landscape is painted with time-worn Southern symbols, from kudzu-choked magnolia trees to rolling piedmont hills, to the Gaffney Peach — the famous fruit-shaped water tower which, as one native notes, “kind of looks like a redneck’s rear end,” mooning the Carolina sky.

About half an hour past the Peach, the familiar scenery fades in the bustling town of Spartanburg, and new sights and sounds signal that one has clearly entered another South altogether. It’s Oktoberfest in Spartanburg, and judging from the clanking beer mugs and costume-decked dancers, the locals intend to celebrate the German holiday with abandon.

Spartanburg hasn’t always celebrated Oktoberfest. The festival was brought here over a generation ago, the brainchild of legendary businessman Richard E. Tukey. Soon after taking over the Spartanburg Chamber of Commerce in 1959, Tukey began criss-crossing Europe, shaking hands and cutting deals to entice the barons of global industry to set up shop in his home town. Launching a German-style holiday to make foreign investors feel at home was the least he could do, a touch of southern hospitality.

Tukey’s dream came true, and today, over 230 international firms line this swatch of Interstate 85 — now dubbed “the Autobahn” due to the high number of German transplants. Corporate jewels from Michelin to BMW have located in the area, making the South Carolina upstate, in the words of one prominent Harvard Business professor, “a lesson in what is required to achieve world-class status.”

But this past October, while the music played in Spartanburg, evidence was mounting that South Carolina’s international aspirations were coming at a high price. That month, the conservative Strom Thurmond Institute issued a report condemning the generous tax breaks the state has been using to lure business — which they estimated would cost the financially-strapped state upward of $420 million by the year 2010.

“The report caused quite an uproar,” says Brett Bursey, publisher of the left-leaning newspaper The Point in Columbia, S.C., who also opposes the business recruitment giveaways. “The politicians were upset that even conservatives were saying they’d had enough corporate welfare.”

South Carolina’s controversy over the costs of gaining global status isn’t unique — similar battles are brewing across the South. While Southern states spend precious resources to chase migrating global corporations, critics are starting to ask hard questions: can the South afford to be a “global player?” And who wins — and loses — when states play the globalization game?

The Rise to World Class

“It was South Carolina in the 1950s and 60s that began to recruit foreign business in an organized way,” says James Cobb, professor of History at the University of Georgia and author of The Selling of the South. But other states followed the Tukey formula, and soon North Carolina, Tennessee, and other Southern states were also looking for business overseas.

The South, once thought of as an economic backwater, was quickly emerging as a vital linchpin in the global economy. Today, the South has become a favorite home for global businesses seeking low costs and access to American prosperity.

“The Southeast is far and away the leader in attracting investment from overseas,” says the June 1998 Regional Economic Review, published by First Union National Bank. The bank’s economists also report that the South accounts for “close to half of all new facilities built in the U.S. by foreign-owned firms during the 1990s.”

In a region where smokestack industries still thrive, many of the transplant businesses are in manufacturing. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the South has six of the top ten states nation-wide in percentage of manufacturing jobs controlled by international affiliates. Overall, almost 13% of manufacturing employees in the region — over one out of eight workers — work for foreign-owned companies.

The global hotspot is Interstate-85, stretching from Richmond down to Atlanta and boasting hundreds of new companies, including U.S. headquarters for dozens of foreign firms. Richmond recently lured Motorola and other high-tech leaders to the 1-85 corridor. South Carolina drew $6.2 billion in foreign investment last year; Georgia reached $11.7 billion.

The international influx is felt in the region’s cultural fabric, too, as states scramble to project a cosmopolitan image for global newcomers. Alabama now advertises Japanese and German schools for expatriate families, while Atlanta has hired models to play Rhett, Scarlett and other Gone With the Wind characters to impress potential investors. In South Carolina, after the German weekly Der Spiegel wrote about the controversy over the state’s flag — which features the confederate stars ‘n’ bars — industry recruiters waged a campaign against the Old South flag, saying it was bad for business to look like the “Cracker Capital of America.”

Great Global Giveaways

So why are corporations from around the world flooding into the U.S. South? Cheap land and cheap labor, cornerstones of Southern policy for decades, continue to attract European and Japanese firms. But one of the biggest reasons the corporations come is because politicians pay them to.

Over the last two decades, Southern states have spent billions of dollars using generous incentive packages — ranging from hefty tax breaks to discounted services to cold cash — to lure the cream of the global corporate crop.

The resulting “bidding war between the states,” with politicians fighting to give away money for jobs, is now legendary. Tennessee began a South-wide spending spree on foreign auto makers in 1980, when it anteed up $44 million in incentives to land a Nissan plant employing 4,000 people — at a cost of $11,000 per job.

The price tag spiraled upward. In 1988, Kentucky put down $150 million to land Toyota, at $50,000 a job. BMW squeezed $150 million from South Carolina, at $100,000 per job in 1992.

In 1993, Mercedes became the biggest-ticket auto deal when it played 26 sites before accepting over $200 million from Alabama — a cost of over $167,000 per job [see “The Art of the Deal,” p. 30]. And this just included subsidies and tax breaks: throw in site preparation, roads, training, and other perks, and each of the deals topped $300 million.

These budget-busting deals — which are often made with little or no public input — raise serious questions about political priorities and how tax dollars are spent.

“You’ll get state leaders who are against paying a dime for social spending/’ says Cobb. “But they’re willing to give a company that just turned a $40 billion profit hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives.”

For many, the Mercedes giveaway was the last straw. Policy experts held countless forums on how the new “arms race for jobs” was bankrupting states; newspaper editors weighed in against corporate bribery; the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis called on Congress to step in; and a lower court in North Carolina even ruled that the giveaways were an unconstitutional use of public funds for private purposes (it was later struck down).

Everyone seemed to agree with Mark Waterhouse, chairman of the American Economic Development Council, when he told the Wall Street Journal that “We in the economic development profession have created a monster that is devouring us.”

The outcry and resulting giveaway lull was short-lived. “There’s been a change in public opinion, but not with the legislators,” says Kimball Forrester, director of the state-wide citizen’s group Alabama Arise. After the Mercedes controversy, Alabama was back to the bidding game, including an $80 million package for Boeing in 1997.

Governors in states like North Carolina have begun asking for bigger unrestricted recruitment funds to sweeten any deal, while other states have opted to devise more innovative — and less conspicuous — financing schemes. According to James Cobb, states have often pledged to swear off incentives when publicity got bad — only to enter the bidding war again.

“It’s a cyclical thing,” he says. “Everybody quits drinking after a bad night. Same with incentives: everybody complains about these bad deals, but when it comes down to it, they think they’re not going to get industry if they don’t. So they get back in the game.”

What Kind of Jobs?

State officials say they keep playing the global bidding game for one reason: jobs. “My job is to get jobs,” says Wayne Sterling, Virginia’s veteran industrial recruiter. “We’re salespeople.”

And to Southerners in depressed areas, what recruiters are selling looks pretty good. International firms tend to hire skilled labor, and according to the European-American Chamber of Commerce, European affiliates nationally pay wages 19% higher than their domestic counterparts, boosting wages all over.

What the South’s global recruiters rarely mention is that wages at foreign firms — although high by U.S. standards — are often a fraction of what these companies pay at home. The BMW plant in South Carolina pays less than a third of what German workers earn — a figure that doesn’t include the health coverage, child care, and other benefits already covered by the German government.

Southern state leaders and incoming companies have also reached a tacit agreement to keep these jobs union-free. Despite the recruitment frenzy, Southern states have historically rejected pro-union shops. As a company executive remarked in the late 1970s, “There are literally scores of companies that have been turned away from Southern towns because of their wage rates or their union policies.”

As for global corporations they often cite the lack of labor activity as a prime reason to relocate in the region. As the Wall Street Journal reported in May of 1993, “German managers have found the laid-back Southern workers more malleable than some of the aggressive, unionized people up North.”

Such words make workers in Europe and other countries uneasy, as they see their country’s corporations migrate to the low-paying and union-resistant South — a direct threat to their jobs at home. Two Canadians recently presented a paper at a conference on globalization, which argued “The results of these [anti-union] policies have been devastating for most Canadians. Several hundred thousand jobs and many hundreds of manufacturing companies have been lost to low-wage American states.”

“[In Germany] it’s not yet like U.S. workers view Mexico, as a threat to their jobs,” says Leah Samuel, a reporter for Labor Notes. “The shifting of operations from Europe to the U.S. South is somewhat new, so most aren’t very aware. But some are.”

Labor advocates on both sides of the border also fear that foreign firms aim to make the low-wage, lean Southern workplace a model for all of their operations — driving down the power and protections of workers world-wide.

“The bosses of German companies want labor relations like the U.S. has,” says Doris Hall, a community activist from eastern North Carolina who met with German labor and citizen organizations during an educational tour in 1996. “We could tell German workers from first-hand experience that this means the companies control the relationship.”

“Going Out Faster than They Come In”

While landing deals with big-ticket companies may give states a quick economic shot in the arm, the rush has often been short-lived. As Southern states are beginning to discover, a policy based on chasing industries on the run suffers a fatal flaw: namely, companies that move in can just as easily move out.

The South has a long history of attracting transient business. In an effort to jump-start industrial development, the region’s recruiters have often chased highly mobile companies with little loyalty to their new location. Nothing has stopped the companies from moving to a state or country which offered a better deal. As one Alabama official complained in 1982, “industrial jobs are going out the back door faster than we can get them in the front door.”

Relying on footloose factories made the South especially vulnerable to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which gave many companies the green light to shift production to Mexico. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the South lost a net total of 127,000 jobs to NAFTA from 1993 to 1996 — almost a third of the country’s net jobs losses. Even more striking, the South accounted for five of the seven states nation-wide which lost jobs disproportionate to their share of the country’s workforce.

According to Bob Becker, an organizer with the Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network, the new multinationals moving into the South aren’t much different.

“Once you have a global economy, these companies aren’t going to stay in the South,” Becker says. “Phillips-Magnavox moved here from Holland in the 1950s. Now they’re in Mexico. BASF, who built a plant in eastern Tennessee is now divided into three companies, with most of their operations in the Caribbean.”

Mike Howells, editor of the Bayou Worker, sees the same trend in Louisiana. “If you have a company moving here from Western Europe,” he says, “They come, stay a while, then move on to Latin America. That seems to be the pattern.”

“It’s very transitional — unless they’re extracting natural resources,” Howells adds. “Then they stay.”

State policies today only encourage multinationals to stay on the run. For one, lavish incentives make moving cheap. “The state has already financed their buildings and given them free land, so they haven’t made a big investment,” says James Cobb. “On top of that, the plant technology is very mobile. They could move anytime.”

The desperate deals offered to corporations also rarely include “clawback” provisions which would penalize a company, or ask them to return subsidies, if they left or failed to meet job targets.

Often, the only option states have is to keep giving companies money to convince them to stay — driving states deeper into the costly bidding game. Called “corporate retention” by development experts, to communities it can seem like job blackmail. In 1995, the state of Virginia felt obliged to give IBM $165 million to build a semiconductor plant with Toshiba in Manassas — a town that had lost ten percent of its jobs when IBM abandoned it a few years before.

Regaining Control

When confronted with the costs and perils of the globalization game, Southern states argue that it’s a matter of survival: if they don’t play, some other state will. “No state can stop using incentives in a world of fierce domestic and international competition,” writes Chris Farrell of Business Week. “To do so unilaterally would be politically and economically suicidal.”

But it’s equally clear that continuing to play the game only cripples the ability of Southern states to regain control over their economic future. Only through cooperation across state and national borders can people affected by globalization gain power over its process. For as workers and community groups challenging the global bidding wars have argued, far from harnessing the winds of global change, the South has only left itself more vulnerable to the whims of corporate interests across the world.

“[Foreign companies] are still mostly interested in cutting costs,” Cobb says. “They’re not coming here to pay twice the local wages or to pay their share of taxes. They find an area they want to invest in — like the South — and see which state is going to give them the best deal.”

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.