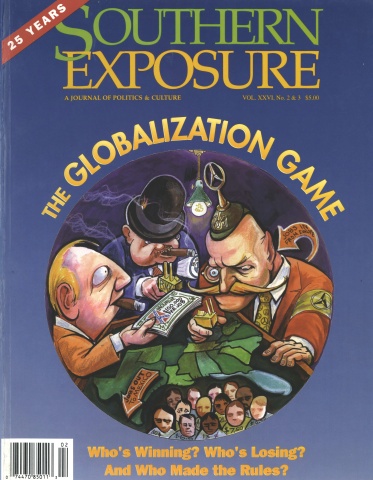

The Globalization Game

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

When the U.S. Federal Reserve Board — the Fed — decides to raise or lower interest rates, people and markets from Hong Kong to Paris to London respond immediately: exchange rates fly up or down; the price of gold fluctuates; investors curse or celebrate their sudden change of fortune.

This is globalization — when actions affect the lives of millions of people across international and intercontinental borders. And today, the intensity and breadth of globalization is truly spectacular:

• When taking a trip in a Ford Escort, chances are the traveler is driving an automobile containing parts from over 15 countries.

• In the U.S. South, over one out of every eight manufacturing workers are employed by a foreign-owned company.

• Over half the largest economies in the world today are not countries — they are multinational corporations, each doing business in hundreds of countries world-wide.

Globalization has always been with us. Ever since the first European explorers set sail in search of wealth some 500 years ago, people and empires have been dreaming of expanding their reach beyond borders.

In today’s age of lightning-quick technology, globalization has taken on new meaning. We watch as the world’s corporations relentlessly scour the globe for cheaper places to set up shop and market their goods to “compete in the global economy.” But as the barons of industry set up new operations here, shut down plants there, and restructure everywhere, the citizens and communities of the world are left to wonder: what’s in it for us in the globalization game?

The South’s business and government elites are aiming to be big-time players in the game. In the face of widespread poverty, boosters have banked the South’s future on becoming a “world-class” region, spending billions of dollars in tax breaks and other incentives to lure corporate goliaths from around the world, which they claim will bring jobs and economic power.

But will playing the game truly bring prosperity to the South? As writers at the Brisbane Institute show in “No Escape from History” on page 26, the U.S. South has always been a central player in the global economy. What has remained the same is the region’s failure to enjoy the fruits of prosperity it creates — what some would call a neo-colonial status in the world economy.

The people of the South must also ask: can we afford to play this game? As we learn in “The Art of the Deal,” spending millions of dollars to entice foreign capital — like Alabama’s quest for Mercedes in 1993 — doesn’t always pay off, and raises serious questions about how citizen’s tax dollars are spent.

And lastly, does the South want to play the game? As William Adler reminds us in “The Journey of Universal Manufacturing,” the darker side to companies on the move are the people and neighborhoods left behind. And being obsessed with reaching world-class status has a price, as Charles Rutheiser argues in “Atlanta: The City of Global Dreams Ain’t Like it Seems.”

Globalization is a game that average people were never meant to win. Kate Bronfenbrenner documents in “We’ll Close!” how corporations are using their new-found mobility to break the will of workers organizing for change. In her analysis of the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), Pronita Gupta shows how international accords are crafted behind closed doors, for fear that the underlying motive — shoring up economic power for the few — would be exposed.

Does it have to be this way? When we talked with some of the South’s leading activists facing globalization, it became clear that, while global change has swept the world by storm, it is far from a natural disaster. Being the work of human hands, globalization can be reshaped by the citizens and communities who will feel the brunt of its impact.

In this issue we feature several “strategy sidebars.” These pieces draw on the lessons learned by activists across the South: citizens making their voice heard about corporate deals in Alabama; workers fighting plant closings in Tennessee; the Black Workers for Justice, organizing workers locally and globally.

Ordinary, hard-working Southerners didn’t make the rules, and were never invited to be equal players in the globalization game. But the work of thousands of southerners makes clear that, with persistence and smart organizing, a vision of a different, more just future can prevail. We have only the world to win.

Tags

Ashaki M. Binta

Ashaki Binta is also a former Senior Field Representative of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Associate Director of the Brisbane Institute/Southern Center for Labor Education and Organizing (SCLEO). Additionally, she serves as Director of Organization for the Black Workers For Justice. (1998)

Hasan Crockett

Dr. Hasan Crockett is professor of Political Science at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia and Director of the Brisbane Institute. (1998)

Dennis Orton

Dennis Orton is a former Senior Field Representative for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Associate Director of the Brisbane Institute: Southern Center for Labor Education and Organizing (SCLEO). (1998)