Facing the Plant-Closing Threat

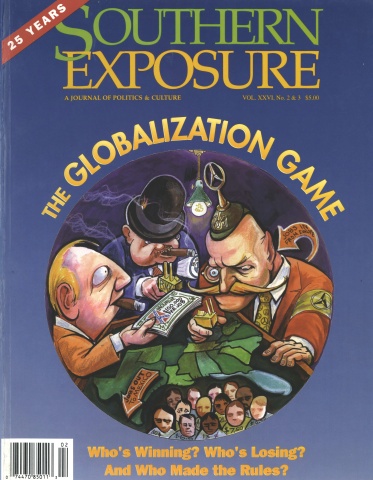

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

In the 1980s, Tennessee’s top brass began billing their state as an economic miracle. Unlike the declining smokestack states of the Midwest, Tennessee was becoming a haven for heavy industry, with corporate crown jewels such as Nissan, GM/Saturn and Firestone setting up shop in the state.

But citizens started to see an underside to the miracle: plant closings. It seemed that just as fast as some companies were moving in, others were moving out. This was supposed to happen in Michigan or Ohio, but not Tennessee — a state which prided itself on having a “healthy business climate,” keeping unions out and wages down.

But the facts were unmistakable: dozens of plants were closing doors, laying off thousands of workers, and moving across the border in search of more profitable pastures.

It was in this climate that a group of workers and community leaders got together and formed the Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network, or TIRN.

“We got out a map, and started putting dots wherever we knew there was a closing,” says Bob Becker, who for six years has been bringing together workers to face the threat of plant closings as an organizer for TIRN. “There were dots all over the place. We knew we had to do something.”

How did TIRN come together?

We formed TIRN in the late 1980s, because a lot of things were coming together at once. One was that the textile workers unions were seeing plants closing throughout the region. There was also a study — “Mountains to Maquilladoras” — the showed how a lot of the plants that had moved from the North to the South, were now moving down further south to Mexico. The great battle was supposed to be between the “rust belt” and the “sunbelt.” But in reality, both regions were losing their jobs to other countries.

What has been TIRN’s strategy in how to deal with these plant closings?

A big part of our strategy has been figuring out what to do, from a grassroots perspective. In 1990 and ’91, we tried something new: we held “Dislocated Worker Thinktanks.” We’d get together 20-25 people who had been through a plant closing and lost their jobs, and ask: “What do you know now, that you wish you had known then?”

During these sessions, things just kept coming out: “I wish I had known the warning signs.” Or “I wish I knew what happens to health benefits after you lose your job.”

Out of this, we created a Plant Closings Manual. And a lot of this manual has to deal with a basic question: “How do you keep your life together?” For example, the workers said that one of the things you need to have in place after a plant closing are numbers for drug and spousal abuse hotlines, numbers for suicide hotlines. Because when people go through this, they are seriously upset.

What are some ways community and worker groups can face the challenge of plant closings?

There are basically three ways. One is to fight to keep the plant open. We’ve tried this, and had a few successes, using worker-buyouts and by pressuring the employer. But it’s a lot of hard work.

The other is to accept it, and focus on dealing with the impact of the closing. People are asking, “I’m losing my job, what next?” Helping them figure that out is an important step. But this shouldn’t be your focus if your goal is to keep the plant open, so it’s important to decide what you want.

And the last strategy is to be more proactive about changing policy, and focus on economic development — about what kind of jobs we want in our region.

What unique challenges do you think organizers working on this issue face in the South?

Tennessee has a wonderful packet they give out to industries that want to locate here. The first thing it says is, “Our state has lower than average wages.” For 30 years, our state, and North Carolina, Georgia and other southern states, have all done the same thing: their idea of economic development is to attract business from Cincinnati or Detroit by being cheap.

Well, then Mexico comes along. Once you have a global economy, these companies aren’t going to stay in the South. And they aren’t going to stay long in Mexico, either. International companies do the same thing.

Your group was recently part of the successful effort to defeat “fast-track” legislation to expand NAFTA. What made your efforts successful?

Our success came from the groundwork we had laid down a long time ago. In the early 1990s, workers would be talking over coffee about how all their jobs were going to Mexico. So we took workers on trips to Mexico, so they could see first-hand where their jobs went. They could see the 17-year-old girl doing their job for pennies an hour. And then they understood, it wasn’t the Mexican worker who took their job, but the company.

So when NAFTA was passed in 1994, people were upset already. NAFTA became short-hand for all the trade agreements and policies that were causing dislocation and trouble. Every time a plant closed, Congressman Bart Gordan would get a phone call: “Why on earth did you support NAFTA?” So when fast-track came up last year, he couldn’t vote for it.

Some Key Plant-Closing Strategies

1) Build a Worker’s Organization: This is the most important step.

2) You Can Save the Plant: Strategies include setting up a committee, studying the warning signs, insisting on a feasibility study.

3) Know Your Rights and Negotiate: Learn plant-closing laws, and negotiate for benefits you deserve.

4) Find Resources for “Starting Over”: Use your community’s re-employment, retraining, job-search resources and financial assistance.

5) It’s Not Easy: Learn where to get support for personal and family needs.

6) Speak Out: Things will change only when workers and communities organize together.

These and other strategies are discussed in detail in Taking Charge, a plant closings manual published by TIRN. For more information, write to: TIRN, 1515 E. Magnolia Ave., Suite 403, Knoxville, TN 37917.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.