Drive

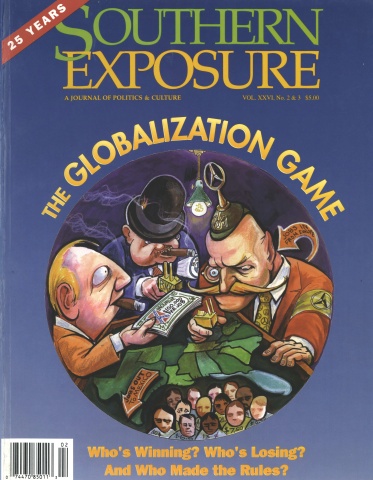

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

Elvis died last week. Summer hangs heavy over the backyard. Kate sits on the stone steps. Lights another cigarette off the last one. Sunlight flecks off specks of dust held suspended in midair. Dumb damp August air. The next-door neighbor’s nephew shoots BBs at bumblebees. Wails in outrage when stung. The ice has melted in the tea. Time to go inside. Time to get a haircut. Time to get up and get the hell out of here.

Kate has decided. It is the decision she knew she would make one day. Today. She has made her decision to go. Tomorrow. She has told no one. Can’t think of a reason why not, except she can’t think of a reason why either. Didn’t want to have to defend her decision. Wouldn’t know how anyway. Just wanted to drive it out. Drive it all the way out.

All of her actions that morning were done to the metronome syllable “now.” She packed up the ’64 Ford Galaxy 500, black with red interior, just as if she were returning to campus: typewriter, stereo, coffee pot, and even that God-awful turquoise macramé owl. Her friend Jane had given it to her when she transferred to Appalachian State. It had been given to Jane by her friend Cindy when she had graduated the year before. No telling how long the dusty blue owl has been circling about in Martin Hall. Kate had been tempted to bestow it on her roommate last semester. Even then Kate had known she wouldn’t be back.

Would not be back. Kate barely squeaked out of high school. Caught her parents off guard when she announced her intentions to go to college. Surprised her teachers. Even her friends seemed dubious. It would surprise no one that she was quitting. Dropping out for all the wrong reasons. She liked the little liberal arts college not far from the Carolina coast, with Spanish moss sagging from the trees like old knowledge. She enjoyed the classes, liked the small town kids that made up the student body, even admired a few of her professors. But . . .

She wasn’t really dropping out because of Winston. No, she had changed. If she had quit because of Winston she wouldn’t have gone back after spring break. She had stuck it out. Too late she had found an answer to his riddle. His penchant for alliteration and a sophomore’s introduction to Freud. He had wondered, as had Sigmund, what do women want? She had been too quick to tease, “What would women want with Winston?” He had teased back, “What would Winston want with women?” Too late. She thought of a better reply too late. “A womb of his own.” Too late. Too bad. Easier to have shared a laugh than to have gotten entangled in solving that riddle. Curse Freud anyway.

Winston. Proud to be cut from the baseball team. From reading one book on the subject he no longer believed in athletic competition. Yet he had no qualms about slashing into lesser intellects with calculated sophistry in minor debates at mediocre seminars on a middle-of-nowhere campus. No, he was not the reason she wouldn’t be back. Kate didn’t know of a reason. Wasn’t looking for one. It was simply time for something else. Time to drive.

Kate exhales a fat line of blue smoke. Starts to light another skinny brown cigarette off the one just finished. She wonders if she will mention that she is leaving. Maybe over dinner tonight. From inside the house she hears her father coughing, calling for her brother to come change the oxygen tank. She knows he’s still at work down at the bottling plant. She rubs her cigarette out on the stone step, drops the butt in an almost empty can of Mountain Dew. On her way through the den she grabs a pack of Lucky Strikes in case Dad’s out. She tosses it to him on her way to the front porch to fetch more oxygen. The green tanks are heavy. She gets the dolly as close as she can, wobbles the tank onto it, then wheels it in place beside her father’s chair. As quickly as she can, she switches the apparatus and sets the gauges. In the process she lets a little oxygen escape to inhale for a pure air buzz. Then she wobbles the empty tank onto the dolly and wheels it to the front porch. It rings a hollow clang. On the concrete as she rolls it from the dolly to the rust stain circle of all the previous empties. Back inside Dad watches the traffic passing. He perks up as Mom pulls in the drive right on time, tires crunching on the blue green gravel. Ambulance siren blares from the television. General Hospital. Kate goes out the backdoor. Lights another cigarette. Family legacy. Flicks ashes onto the clover.

Next morning Kate is awake before dawn. Listens to the mockingbird in the cedar tree. Hears the echo from the myna bird on Old Miss Matthew’s side veranda. Who was mocking whom? Endless avian litany. It had always been, would always be like. . . ? Kate tries to isolate just one thing. Everything just sort of grew more dense without really changing. Shopping malls . . . interstates . . . kudzu . . .

Heading for the hills instead of back to college was a subject that never came up. Not over dinner the night before. Not that morning as she drives Mom to the factory one last time. It is the wrong way to do things. Kate knows that. But how to explain to her mother the things she doesn’t understand herself. It is time to go. Kate knows that, too. But she doesn’t know how she knows it. It had to be now. Or never.

A peck on the cheek. Quick good-byes for a couple of weeks, not for a lifetime. Kate watches her mother show her ID before entering the textile mill. Kate wonders again about the fence with the spiraling barbed wire top. Was it to prevent a break-in? Or a break out? From the top of the concrete stairs, Mom turns to wave goodbye before entering the windowless building. No, not windowless. There are windows. Small. High up. Above the heads of the workers. Painted over.

Kate slides in an 8-track. Patti Smith. Waits for the crosswalk to clear. It’ll take a while. An army of women, uniformed in pastel polyester, helmeted with Toni perms, scurries from parking lot to factory. She looks at the expressions on their faces as they pass. So many variations. Kate tries to guess who is excited about a new grandchild, relieved for a few hours from a drinking husband, concerned about a late period, mad as fire about the new quota set for old machines, having an affair, joyful about finding the Lord, or simply tired before the day begins. Others are women she worked with after school and weekends at Tastee Freeze. A few she recognizes as former classmates from Southern High. They were the ones who had quietly left school, quietly gotten married — or not — and were quietly raising kids of their own. Lucky to have gotten on down at the mill.

There’s Aunt Candy wearing tight black wranglers and a checkered flag tee over stiletto b-cups. As a preteen, Kate, having only vague suspicions about the suspension variations of bras, had hoped her breasts would grow out pointy, too. Fortunately, she outgrew that desire. But she still salted her watermelon after spotting Aunt Candy salting hers down at White Lake several summers ago. Back then Kate and her sisters would practice holding cigarettes like Aunt Candy. Flicking away ashes with cool, emphatic elegance. Aunt Candy teased her bleached hair, smoked filterless Camels, wore hot pink nail polish even on her toes, and had absolutely no qualms about arguing with Uncle Leon. Anytime, anywhere. And she was always right. Almost. The woman has no idea the impact she had on good girls from good families. The whole point was — she wouldn’t have given a damn if she did know. It was intoxicating. She spots Kate. Comes over. Hops in.

“I been worried about you, Missy.” She yanks out Patti Smith mid-screech. Turns on the radio, pushing all the buttons until she gives up. Turns the dial for a country station.

“Well, I’m glad someone is, but why are you worried about me, Aunt Candy?” Kate looks into the back seat where Patti landed.

“Cause I heard you were quitting college to get married. Dumb idea. And I’m not your aunt.” Candy lights a Camel.

“Where on earth did you hear that?” Kate has never been good at keeping up on gossip, especially about herself. Couldn’t imagine anyone’s life being so boring that gossip about her would spice it up.

“Let’s just say I’m acquainted with his daddy.” Candy looks straight ahead but nods as if to say she understands a hell of a lot more than she’ll ever admit to. “But then I heard you broke it off. Good girl. You stay in school.”

“Well, if you happen to be talking about me it wasn’t serious to begin with.” Aunt Candy’s never been the best source for news. Must have gotten mixed up on who this tidbit was about. Mixed her up with one of her cousins. Debbie, maybe. Or Janette. Or even Dwight, for that matter.

“I almost bought me this car, you know that?” Candy flips open the glove compartment. Starts glancing though the worn moss green memobook with the one-side-blue/one-side-red pencil wedged though the spiral at the top. “Saw it on a Tuesday. Had to wait till payday. Gonna buy me this one. Come Friday afternoon the man said he sold it that morning. Wouldn’t say to who. Wasn’t on the lot a week. Should have know it would be your daddy to buy it. This one could be doing it over at Jet Motor Speedway.”

Kate watches Candy studying her father’s notations. Carefully printed block numbers, shakier after the stroke, but all there: dates, mileage records, oil changes, each and every repair. It dawns on Kate. That’s how he knew. Every time. Whenever she cut school he would ask before a week had passed, “Ever been to Fayetteville, Kate?” or, “Wonder what was going on in Raleigh last Wednesday.” Never a big deal about it. Must not have told mom. But he always made sure she knew he knew. End of conversation. Now Kate knew how. He read the speedometer. Kate smiles. It should have been so obvious but it had confused the hell out of her. Had her cutting more classes driving further afield trying to figure it out. She’ll have to think of a way to let him know she knows without admitting anything.

Candy stopped talking. Kate tries to remember the last thing she said. “Thought Uncle Leon gave up racing after that last crash-up over at Trico.”

“Not for Leon — who ain’t your uncle. For Little Leon — who ain’t your cousin neither.” She flips backwards through the memobook to double-check the facts. Satisfied, she tosses it back in the glove compartment. “Yes, ma’am, tell your daddy I want to buy me his car.”

“Ain’t his to sell. Share it with my sisters and we’ll never agree to sell it. Hell, we never agree on anything.” Kate laughs, lights another off the last one.

“Well, I got sisters too and y’all will get tired of sharing it. Better not sell it to nobody else. Kate laughs louder. “Yes, Aunt Candy, you’re probably right. It’s mine for two weeks, then not for a month. If I decide to sell my third I’ll keep you in mind.”

Candy’s nod settles it better than a handshake. The deal has finally gotten off the ground. One third promised better than no third at all. She’ll have this car yet. It’ll run better after Ross has it for a couple of years. He’ll keep it running fine for his girls. She’d buy a car from Ross anytime. Hell, if the boy can’t hold any steadier than his daddy, she might just take it on the track herself. “Thank you. I’ll hold it to you. But like I said, I ain’t your aunt.”

“What do you mean you ain’t my aunt anymore? Did you really leave Uncle Leon for good this time?” Kate tries to picture one without the other.

“Haven’t left him. Just divorced him. And as soon as my youngest turns 18 I’m leaving home. Florida. Heard they’re short on nurses. If Leon sobers up he can come with me. Or not. Let me tell you one thing, there will come a day when you’ll have to lean back, look way up, get a crick in your neck just to bitch at your sons. That’s when you’ll know life is passing you by.” Candy rolls down the window to share an inside joke with two women jaywalking behind them. Turning back to Kate, “And I never was your aunt and Leon ain’t never been your uncle neither.”

“So, how come y’all’re always at my family reunions?” The twang of country music is giving Kate a headache. The folksy, hokey commercials are too much. She takes a bet on a Bob Seeger bootleg. “Leon’s granddaddy’s old maid eloped with your mama’s step-grandma’s half brother. She raised his kids but none of her people are related to his. It all hinges on a marriage that never took place no way. Claim they did it in Dillon.” Candy glances with upturned nose at Kate’s 8-track collection.

“So what does that make us?” Kate contemplates the obtuse geometry of her kith and kin.

“Total strangers.” Candy cuts Bob short mid horizontal bop. Turns the radio back on. It’s going to be country or nothing. And Candy ain’t one to settle for nothing.

“So, how long have you been at the mill anyway?” Kate watches the crowd of hurried women thin out.

“Since L&M started handing out pink slips. Didn’t waste no time getting one to Leon. Got his in the first batch. Four hundred ninety-six let go Friday before Fourth of July. Happy Independence Day. With the tobacco factory closing down the Blue Light Diner lost all the regulars. Going after the college crowd. Now I can’t begin to live on college boy tips. One of those Duke brats told me he liked older women. Gave him Mama’s number. Let her preach to somebody else about Jesus for a change. Next week I go graveyard. Start taking classes over at Tech first thing Monday morning. Now that my divorce is final I qualify for financial aid. Displaced Homemakers Program.” Candy shakes her head and snorts. “No more sleeping till noon, bridge party teas, shopping all day, and trying out recipes from the Sunday paper, begins laughing.

“Honey, don’t you believe it.” Tammy Wynette belts out her anthem right on cue. Kate reaches to turn it off but Candy smacks her hand. Suddenly Kate feels about seven years old again. Not knowing what to say, she considers the divorce. “Guess Tammy knows a lot about Leons.”

The last stragglers from the parking lot bolt through the crosswalk as the air swells with blaring horns. Traffic hasn’t moved in twenty-seven minutes. Candy opens the car door, saying over her shoulder, “Tammy might know a hell of a lot about good old boys but she don’t know a damn thing about me. Don’t nobody know nothing ’bout me.” She hollers at the guard to hold the gate. He does. She strides through without hurrying. The gates clang behind her.

Kate pulls through the crosswalk to park just on the other side. Drivers, relieved that the wait is over, speed past as she considers her choices. It’s not simply a matter of taking a semester off. To not go back would mean losing her grant money, getting knocked off her father’s disability checks, and having to pay back the student loan that made up the bulk of her tuition. Dropping out now might mean never getting a chance to go back. Going back was the best option. Dropping out to move to a town where she didn’t know anyone, didn’t have a place to stay, didn’t have a job waiting was a bad idea no matter how you looked at it. If things didn’t work out would she be able to live with the consequences?

In the rearview mirror she watches as two women try to convince the guard to open the gate. He pretends it isn’t up to him. They flirt. They tease. They pretend it doesn’t matter. After a few moments of play he lets them though. Kate thinks about 2:30 p.m. The women will flow out as if exhaled by the brown lungs of the factory itself. They will pour forth from the bottleneck door to cascade down concrete stairs. At the gate they will automatically hold out their arms to show that they are not forgetting about a remnant, or pillowcase, or spool of thread. The gesture is as automatic as the flash of IDs at the gate in the morning, or the smile they offer to their supervisor’s bosses. The younger women spring ahead, as if fleeing from fate. They are first through the gates to jump into idling pick-ups, or Chevy vans with shag carpet interiors.

Then it’s the oddest thing. Makes Kate shiver every time. To watch the slow flowing river of women who have been up at the mill for years upon years. All the women have become gray-haired, whether they were gray at 6:30 a.m. or not. The lint from the fabric sticks to hairsprays, dyes, and to the Afro-sheen coifs beneath do-rags. Bending over sewing machines, working as fast as possible to make quota, has given all of the women the same wrist, neck, and shoulder aches. From hours spent doing the same job in the same rhythm, all the women move in the same way. From the mind-numbing monotony they wear the same expressions. Could only eight hours have elapsed? Eight hours of airless, droning repetition.

How many times? Too many times. This summer. Last summer. And the one before that. Once or twice a week Kate waited for her mother at the end of her shift. She would see her exit the door at the top of the stairs. Kate would start the engine, put her cigarette out, and wait. She would lean over to open the door only to have the woman — a stranger — pass right by to join her carpool, or board a bus. That might happen two or three times an afternoon, all within an eternity of twenty-seven minutes. And it was an even eerier feeling to be watching so carefully, to be absolutely sure not to be mistaken this time, only to jump as her mother opened the door to slide in beside her. Kate knew she would never tell her mother this, would never bring it up to her brother or sisters. What if it never happened to them?

Yes. If she had to. Kate could live with the consequences. Now or never. Kate starts the car. Oh, how she loves the way the ’64 Ford, black with red interior, lifts from park to claim the road. She meanders and circles and loops through her hometown to make absolutely certain. American tobacco, the Bulls’ ballpark, and churches of austere stone parade by. Maneuvering confidently, she approaches Five Points from every direction. Down Main St. for a last glance at the old library, cotton candy pink, plump cheeked, overfed and holding its breath. She cuts through the empty parking lot of what had been Sears before it led Thalheimer’s, Belk, and J.C. Penney on the long march to the malls. Crossing the tracks for a quick trace along the edge of Little Hayti. Doubling back. One more time from the west through Five Points, this time on Chapel Hill Street. She pauses for a moment to glimpse the newspapers rolling off the press in the window of the Herald-Sun. Then on to her favorite downtown scene, which is not a scene itself, but a reflection. Of a stone church and willow tree in the smooth tinted surface of an office building. Best seen from the corner of your eye on passing. The road dips, lifts curves, and the scene is gone. Waiting at the stoplight, Kate scans the area. Suburban sprawl crawling into town in the guise of police, fire, and TV stations. Counter-clockwise on the Downtown Loop leaving home headed west. In her rearview mirror she notices the gap-toothed skyline. First time she’s noticed it since the Adshusheer came down. Incredible. The Adshusheer Inn, only ten stories high but a block thick; magnificent but squat. It had stood stoically beside the slender seventeen-story Catawba Central Bank, where Superman would have lived had he been a Tar Heel. Together they had been the Mutt ‘n’ Jeff of her hometown skyline. Alone the bank building seemed exposed, and oddly fragile.

OK. Like the mountain man said, you can’t go home again. But even if you stay in place, you can’t stay in time. Now. Or never. No, not never. Now. Time to drive.