Changing International Agreements, Starting in Your Own Backyard

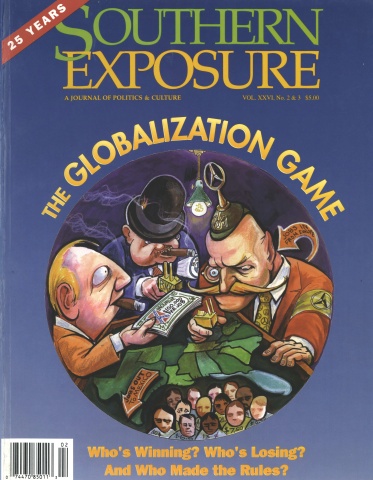

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

As you hear more about the global economy, it seems that new acronyms and new economic agreements are being created at an alarming rate. Terms such as NAFTA, GATT, WTO, IMF, and MAI (see glossary below) are thrown around as though they are common parts of speech. It’s hard to keep up — much less understand how these trade and investment pacts will affect your state or community.

However, these agreements can have incredible and often devastating impacts right down to the local level, usually affecting jobs. One such agreement, the Multilateral Agreement on Investments, or MAI, is one of these little-understood but potentially destructive accords.

MAI: Jargon to English

The Multilateral Agreement on Investments is a new international economic agreement that would make it easier for corporations to move their investments — both money and production facilities — across international borders.

The MAI is currently being negotiated at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — a global forum with 29 members representing the wealthiest nations, including the United States.

Proponents of the MAI claim that the agreement would reduce inefficiency caused by burdensome regulations, reducing obstacles to overseas investments and opening up more foreign markets. They claim these steps will help to spur the U.S. economy and create high-paying jobs. Proponents also argue that the U.S. can protect this country’s interests by exempting existing laws they want to protect.

Critics argue, however, that this agreement would end up tying the hands of governments by limiting them from regulating or restricting foreign investments, granting multinational corporations almost unlimited rights, with few or no responsibilities.

Some of the most controversial provisions within the MAI that directly affect state and local communities include (in MAI jargon):

“National Treatment:” This provision requires countries to treat foreign investors no less favorably than domestic firms. Countries would not be able to place restrictions on what foreign investors can own, meaning sectors such as natural resources or even broadcasting could be owned and operated by foreign corporations. It also means that programs designed to assist domestic firms, such as small business initiatives or set-asides for minority-owned businesses, would no longer be allowed. Lastly, national, state, and local governments could no longer require corporations to hire a certain percentage of their workforce locally.

“Most Favored Nation:” This provision requires that governments treat all foreign investors and foreign countries the same under regulatory laws. Therefore, countries could no longer use economic sanctions, such as those used successfully against South Africa under apartheid, to pressure a nation to improve their human rights record. It would also make it difficult for governments to enforce labor and environmental standards.

“Performance Requirements:” MAI would limit laws that require investors to meet certain social or environmental conditions in order to be eligible for subsidies or government grants. Important gains that could be overturned include living wage laws, job-creation requirements, and environmental laws and standards. One important program vulnerable to this provision is the Community Reinvestment Act, which has established rules to promote bank investments in low-income areas.

“Uncompensated Expropriation:” Governments would have to repay foreign investors immediately and in full if they deprive them of any portion of their property. However, the language in this section is so broad that it can be used against environmental or labor standards that cause a company to lose some profit.

“Repatriation of Profits:” This provision would ban countries from preventing investors from moving assets — money or production facilities — out of the country. In other words, corporations would be able to move in and out of countries with little regard for the local or national impact. Therefore, a state that has spent millions in subsidies to lure a corporation has no guarantees that the corporation won’t pick up and leave a few years later if it finds another location willing to provide even greater subsidies or lower wages.

“Investor-to-State Dispute Resolution:” This would allow corporations to sue governments and seek monetary compensation if they feel a law violates the investor’s rights. Foreign investors would have the choice of either suing a government before an international tribunal or in the country’s domestic court. Once again, this provision weakens corporate accountability within any particular country.

The main question the MAI raises is one of accountability. By weakening government protections, the MAI places an enormous amount of power in the hands of multinational corporations that are accountable to no one except their stockholders. Democratically- elected officials and governments are largely given only “rubber stamping” authority.

While corporations gain all the rights and few responsibilities under the MAI, workers, communities and the environment must pay the price in this “ race to the bottom,” where investment gravitates to areas with the lowest wages, working conditions, and environmental standards.

High-tech Organizing Delays the Agreement

The OECD has been quietly negotiating the MAI since 1995 and had hoped to seal the agreement this past April. However, a draft of the 150-page agreement was leaked to the public in 1997, prompting outrage worldwide by grassroots groups, and inspiring a successful high-tech organizing campaign.

Citing concerns about national sovereignty, lack of labor and environmental protections and issues of corporate accountability, groups across the world turned to the Internet to quickly spread information and signal a call to action. Activists bombarded local and national legislators with faxes, phone calls, letters, and e-mails demanding an end to the MAI negotiations until further community input and standards were put in place. A number of cities around the world, including San Francisco, passed resolutions declaring their cities to be “MAI-Free Zones.”

This victory, which came at the same time labor and environmental organizations had successfully defeated President Clinton’s attempts to expand NAFTA through “fast-track” legislation, has boosted confidence among citizen organizations that grassroots activism can change global trade and investment agreements.

Where It Now Stands

Due to grassroots pressure, the negotiations were put off until October 1998. The effects of the Internet campaign are still being felt; some countries, such as the U.S., are demanding waivers for some of the provisions. However, there are no promises that the wish list of waivers will ever become reality.

MAI negotiators have also discussed adding references to labor and environmental concerns in the preamble, which critics charge would only serve as window dressing with no enforcement authority.

If the MAI fails to be ratified at OECD, a similar agreement may resurface in one of the other trade and investment bodies, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). If MAI-type language was considered by the WTO or other global associations, it might prove an even greater challenge for community-based groups to monitor and push for provisions that protects workers and the environment.

How to Get Involved

If you are interested in learning more about or joining organizing efforts for citizen input in the MAI and other trade pacts, there are many organizations you can contact, including The Preamble Collaborative, and Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch (see resources section for more information).

Tags

Pronita Gupta

Pronita Gupta was the executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies from 1996 to 1998. She has since served in several positions, including the Deputy Director of the Women's Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor and as Special Assistant to the President for Labor and Workers at the Domestic Policy Council during the Biden administration.