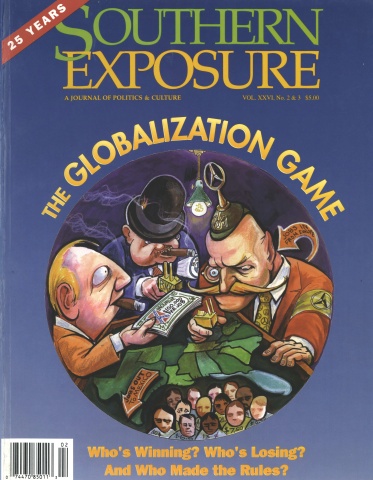

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

In the late spring of 1997, nearly 100 foreign journalists descended upon Atlanta for a four-day, all-expense-paid tour sponsored by the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau. The extravagant junket — complete with a moon-lit dinner on Stone Mountain Lake and a barbecue buffet on the grounds of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell’s renovated home — was intended to heighten Atlanta’s appeal as global tourism hotspot, and to counter the negative portrayal the city had received at the hands of the foreign press during the 1996 Summer Olympic Games.

Atlanta’s boosters had thought the games were their ticket to international status and a great global image, but much of the world’s media begged to differ. In report after report, journalists lambasted Olympic organizers for their disorganization and smugness, and took the city to task for its crass commercialism and lack of a discernible history, culture, and identity.

Trying to restore its image as a “world-class city,” the Convention and Visitors Bureau wined and dined the journalists, and treated them to a VIP tour of prime attractions. But the junket was a typically Atlantan response to a problematic situation, as a good deal of the city’s success over the last century and a half has been the result of tireless self-promotion and public relations to attract global corporate interests.

An Olympic-Sized Identity Crisis

Atlanta has always been something of a creation of its own imagination — or rather, the imagination of a cadre of visionary dreamers that stretches from 1890s New South promoter Henry Grady to 1990s Olympic organizer Billy Payne. A sort of future-oriented place where the rhetoric consistently runs more than a few laps ahead of the facts on the ground.

Two years after the Olympic Games brought the city unparalleled attention at home and abroad, Atlanta still lacks a clearly defined identity. Within the United States, Atlanta is best known for its baseball team and its airport. In a recent survey, more than one-third of Americans were at pains to come up with anything characteristic of Atlanta at all.

For many Europeans and Asians, Atlanta conjures up images of the moon-lit and magnolia-scented Old, rather than the New South. When these visitors encounter a vast complex of modern office buildings, shopping malls, planned unit developments, and expressways that sprawl over the hills and vales of the north Georgia piedmont, they are left to wonder: “What is Atlanta?”

Atlanta’s ambiguous identity is no accident, for successive generations of some of the most dogged urban boosters in the United States have regularly re-invented its form and image. Much like its ill-fated Olympic mascot, Izzy (originally known, fittingly, as Whatizit?), Atlanta’s defining feature has been its ability to morph, to reconfigure itself into an amenable locale for global capital.

The Global Corporate Hothouse

Yet while Izzy crashed and burned under the glare of world-wide ridicule, Atlanta has been a success with U.S. and foreign corporate executives, who, for much of the past decade, have regarded Atlanta as one of the most accommodating places in the world to do business. Atlanta possesses a loosely regulated, hothouse atmosphere made to draw investment dollars.

Over the past 30 years, billions of dollars in foreign investment — some $8 billion in 1997 alone — have joined the still larger flow of domestic capital that has fueled the engine of a metropolitan growth machine. At the same time, many Atlanta-based corporations have expanded their overseas operations, while almost half a million immigrants and refugees have joined with legions of corporate transplants and emigres from New York, California, and the Rust Belt to bring an unprecedented diversity to Atlanta’s social and cultural landscape.

Atlanta has always had global aspirations, but it wasn’t until the late 1960s that the Capital of the New South started promoting the notion of it being “the world’s next great international city.” Following a model that had proven itself in attracting national capital and institutions to the city, the Chamber of Commerce hawked Atlanta’s virtues in the European business press, while elected officials invested nearly five billion dollars of public funds into building the necessary infrastructure to lure global interests — including the Georgia World Congress Center, a new international airport — and sent scores of trade missions to the business capitals of Europe and Asia.

As in many other southern states, cheap land, low taxes, non-unionized labor, limited regulations, as well as various and sundry investment incentives were major draws for investors in the U.S. and abroad. The Atlanta metro region went on to snare the vast majority of outside investment that has found its way to Georgia.

The global dollars started pouring in during the early 1970s. It was then that Greek, Kuwaiti, and Saudi investors helped finance two of downtown Atlanta’s major developments — the Omni International (now CNN Center) and the Atlanta Center, Ltd. (now the Hilton Hotel and Tower) — while a Dutch firm purchased one of the city’s leading corporate citizens, Life (Insurance Company) of Georgia.

Between 1975 and 1984, the number of foreign companies with offices in Atlanta mushroomed from 150 to 780, with 240 of these being U.S. headquarters for these firms. Most of these companies were from Canada, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, but they also included branches of the world’s twenty largest banks, making Atlanta second only to Miami as a center of international finance in the Southeast. By 1984, foreign companies had invested more than $3 billion in offices, warehouses, and manufacturing plants throughout the metro area, as well as hundreds of millions more in real estate speculation.

But global investment really took off when former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young was elected mayor in 1981. Young spent his tenure in office vigorously recruiting international investors, traveling so often that he was jokingly referred to as the “absentee mayor.”

Northeast Asia was an especially coveted target, and thanks to Young’s exhaustive networking, by the 1980s Georgia boasted more Japanese-owned facilities than any state but California. By the end of the decade, Japan had more facilities and employed more workers in Atlanta than any other foreign country.

A (Low) Place in the Global Economy

Today, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan account for 40 percent of foreign investment in the state of Georgia. However, within Atlanta itself, Canadian and Western European firms continue to play a significant role in the metro area economy, accounting for slightly more than two-thirds of the foreign-owned facilities and more than half the workers employed by foreign-based firms.

In particular, European investors continue to be major players in the city’s hot residential and commercial property markets — many of the corporate trophy buildings constructed over the last ten years in downtown and Midtown Atlanta were at least partially financed by European capital.

Overall, the number of foreign-based firms with operations in Atlanta increased by some twenty percent between 1990 and 1997, and they currently employ more than 80,000 workers. As impressive as these figures may sound, these jobs constitute only some four percent of the total metro area employment.

And while the Chamber of Commerce makes much of the fact that Atlanta is home to the U.S. headquarters of 315 foreign-based companies, most of these are of small to medium-sized firms, rather than major corporate entities. Most of the facilities operated by foreign-owned firms specialize in sales, distribution, and warehousing.

As a result, Atlanta’s role in the new global division of labor resembles its former function in the U.S. urban hierarchy: a regional node for distribution and, to a lesser extent, production, rather than a command and control center. In other words, Atlanta is not so much a place where decisions or products are made, as it is a place where decisions are carried out and goods stored and shipped.

International Success Symbols

Of course, foreign investment constitutes only part of Atlanta’s international presence. Foreign trade has increased dramatically in recent years, with metro Atlanta accounting for more than two-thirds of Georgia’s global exports. With more foreign investment and trade have come increased numbers of foreign visitors, and it is estimated that roughly half a million foreign travelers visited Atlanta in 1997, with Britain, Germany, and Japan — the three largest sources of foreign investment — accounting for nearly half the total.

Over the last two decades, a number of Fortune 500 companies with operations of global scope — including Georgia-Pacific, United Parcel Service, and Holiday Inn Worldwide (the latter British-owned) — have relocated their corporate headquarters to Atlanta. These new arrivals join a number of other transnational “corporate citizens,” ranging from the well-known Coca Cola and Turner Broadcasting System (now part of Time Warner), to dark horses like the Southern Company, which has quietly emerged as the largest privately owned provider of electricity in both the United States and the world.

But a city’s “world-class” status is not made by foreign investment and trade alone, and city leaders have made symbolic efforts to cast Atlanta in a cosmopolitan light. The first step came in the early 1970s, when city officials renamed Cain Street — which connects the World Congress Center with the expressway — “International Boulevard.” In preparation for the Olympics, efforts were made to enhance the road’s “international” character through extensive use of flags, globes, and other worldly symbols.

Exiting the expressway, the traveler passes under a proscenium of flags, then, crossing Peachtree Street, under twin globes set in the facades of the Hard Rock Cafe and Planet Hollywood. The intersection of Peachtree and International — temporarily re-named “International Square” during the Olympics — is marked by a large mosaic of the world rendered in black and red asphalt tile. Unfortunately, like the mysterious lines on the Plains of Nazca in Peru, this globe can only be seen from above, and most of the thousands who pass by each day are completely oblivious to it.

Continuing westward, International bisects the central square of Centennial Olympic Park, which is bordered by a grove of flags from previous Olympic host nations, before terminating at the new Georgia International Plaza, which during the Olympics possessed yet another ceremonial thicket of world flags. The overall effect of this all-too-literal inscription of internationality into the fabric of the city, however, is neither global nor local, but, as the international community proclaimed in 1996, provincial and tacky.

The Immigrant Stream

Atlanta’s real international boulevard is located some two dozen miles to the northeast of the official one, along an eleven mile stretch of Buford Highway near the cities of Doraville and Chamblee in suburban DeKalb County. Like many cities of the Deep South, Atlanta was never an immigrant destination. This began to change during the 1960s, when small numbers of immigrants began arriving from Latin America and Asia.

During the 1980s, Atlanta became a favored location for the resettlement of more than 10,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, many of whom resided in apartment complexes along Buford Highway. In the 1990s, the stream of refugees broadened into a wide and mighty flow of thousands from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and Eastern Europe. Refugees, though, were themselves greatly outnumbered by legal and illegal immigrants from Mexico, China, Korea, India and several dozen other countries.

In the old strip malls that flank Buford Highway and along Riverdale Road in Clayton County and other locales in the metro area, ethnic entrepreneurs have opened up hundreds of restaurants, groceries, and other specialty stores to cater to the needs of the region’s increasingly multicultural population. The immigrant communities also boast the now familiar array of social, cultural, and business organizations as well as a number of small, but growing, banks that are partially capitalized from abroad.

Although an accurate count is difficult, researchers estimate the number of foreign-born Atlantans at around 435,000, or almost twelve percent of the metro population. While some of the foreign-born are expatriate employees of foreign-based firms, the vast majority are immigrants and refugees.

Atlanta’s recent arrivals often find themselves on the margins. The metro region’s public culture remains rendered in shades of native-born white and black. Of all counties in the area, only DeKalb — where almost 40 percent of the foreign-born live — has made efforts to officially embrace multiculturalism.

In fact, in many places the increase in immigration has stimulated a backlash, such as the city of Smyrna in suburban Cobb County, where city fathers, fearing the same kind of “un-American” landscape to be found along Buford Highway, passed an ordinance that banned signs in foreign languages.

And sheer numbers have not yet translated into political power. Many foreign-born are not yet citizens — Atlanta has the dubious honor among American cities of having the longest wait for obtaining citizenship — and there is considerable tension between and among different Asian, Hispanic, and other groups. Yet it is virtually inevitable that increased numbers, coupled with the economic success of many immigrant entrepreneurs will eventually translate into some degree political influence.

Global Atlanta: Myth and Reality

While Atlanta’s global connections are undeniable, it is another thing to know what to make of them. While city leaders envision “a world-class city on par with New York, London, Paris and Tokyo,” in the words of an Olympic organizer in the summer of 1996, such fantasies have not translated into overall prosperity or economic power.

Atlanta is more comparable to other Sunbelt metropolises like Los Angeles, Miami, and San Francisco, cities that serve to link newly industrialized regions with the global economy. Atlanta’s sphere of influence is the Southeastern U.S., long considered by many to be an internal colony of the North, but now the nation’s most economically dynamic region.

As it pursues global dreams, Atlanta may find that trying to become a player in the international economy means greater interdependence, and the prosperity it brings can be more ephemeral than eternal.

“Finally Comes Despair.”

What happens when globalization hits? A story from North Georgia.

By Ann Mittendorf

In 1996, the plant that Ann Mittendorf had worked at for six years closed its doors in Loganville, Georgia, and moved to Mexico. Since then, she has joined the organizing department of the textile union UNITE! in North Georgia.

Recently, she offered the following testimony at a forum on globalization held by the Atlanta Book Club, saying, “Since NAFTA, my job along with millions of others has been eliminated. I don’t want to be a number, forgotten in the haste of the rush for the border.”

I would like to begin by introducing myself. My name is Ann Mittendorf. I am a wife and a mother of two, and I have been an active participant in the labor force for many years.

I worked at Lithonia Lighting in Conyers [Georgia] for eight years. At one time we were a big business, supplying jobs for many families. Now, the big business is moving to Mexico. The workers who are still there have suffered greatly and pay more for the few benefits they still have.

I then went to work for the Kuppenheimer Men’s Clothing chain in Loganville. I worked there as a seamstress for six years and served as the President of the local union. Our plant closed in October of 1996, and [since then] I have been working for UNITE!, the union that represented the Kuppenheimer workers. I would like to tell you about the ordeal that the workers encountered when the plant closed.

Can you comprehend how it feels to find out that your job has ended? I remember , the first thing that we felt was disbelief. We thought, “Maybe it’s not true. Some mistake was made and soon we’ll be hearing that it was only a rumor.” Then, slowly, one by one, people began to realize that the plant was really going to close.

Then comes panic. “What’s going to happen to our insurance? Will we lose our retirement? Why doesn’t the company answer our questions?” Everyone is so edgy we’re taking it out on our families.

Then you get angry. You think of all the days you came in sick but gave your best anyway. It seems so unfair that your whole life has been turned upside down. You’ve worked so hard to achieve success and now there’s nothing left.

Finally comes despair. You realize you have to let go. “Who knows what lies ahead for us? How many will find another job? How many will lose their homes?”

I want to tell you about some of my former co-workers, Kathryn and Montine. They had worked at our plant for over 30 years. They have put all of their adult lives into their jobs — morning after morning without fail. Now, all of a sudden, they will not go to work. How many mornings will they lie awake in tears — feeling that all their years were spent in vain? How do you say goodbye to so many memories? How do you start all over again? This happened a year ago, and neither one of them has found a job yet. They’re both over 55, and even though we’re not supposed to be subjected to age discrimination, we all know these things happen every day.

Then we have Pat and Lynn. Pat’s husband has cancer, and Lynn just returned to work after having a stroke. They both had to deal with losing their medical benefits or paying a hefty price to even continue these benefits temporarily. That’s not easy to do on an unemployment check. Pat did find a job, but she makes less money. That was her only option, in order to have some kind of health coverage for her husband. Lynn is now facing the end of her unemployment benefits with nothing to look forward to.

Then we have Sharon and Martha. Sharon has one child and gave birth to twins shortly after the plant closed. She cannot afford to work because she cannot afford childcare for three children on minimum wage. Marsha has one child. But her husband is unemployed. What kind of holidays will they have? There won’t be many presents under the tree.

America is not made up of companies and corporations with no emotions, but people tike these who have real feelings — real families — and real problems.

This is not an isolated case; it affects millions of Americans who have no job — because their job has gone to a family of South Americans who are willing to work a sixteen-hour day for pennies. Do they benefit from the jobs that are going over the border? No, they suffer too. Wages in Juarez, Mexico, have dropped from $l/hour to 70 cents/hour since NAFTA passed.

And who gets the profit? Certainly not us, or people in Mexico or other countries. We are paying for it at the expense of our very hearts and souls. Only the corporations come out ahead.

We have to stop this raping of the American family. We have to educate the people around us. We have to make sure people are registered to vote. We have to find out which politicians are truly on the side of the people, and which ones are out only for personal gain. We have to make sure that we’re not just another number.

I hope when you leave here tonight, you leave with a sense of the devastation that is taking place around us daily — and the need to get organized.

Tags

Charles Rutheiser

Charles Rutheiser is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Georgia State University in Atlanta. He is the author of Imagineering Atlanta, published by Verso. (1998)