The Art of the Deal

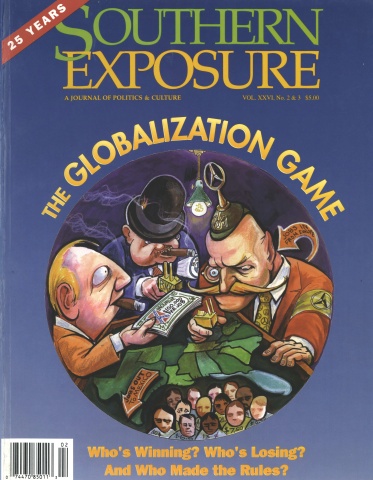

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 2/3, "The Globalization Game." Find more from that issue here.

In today’s economic environment, corporate loyalty seems all but extinct. Using their ability to relocate as leverage, corporations have taken to playing states off each other to get subsidies and benefits in exchange for jobs. The result has been the famous “war between the states,” where states compete for corporations by offering bigger and better incentive packages.

One of the best-known examples of this controversy is the case of Mercedes-Benz’s move to Alabama. In 1993, Mercedes announced its intentions to build an automotive assembly plant in North America to produce a new sport utility vehicle. What followed was an all-out bidding war between 62 locations in over 20 states — many in the South — to land the German giant.

Interestingly enough, Alabama was not on Mercedes’ top list. However, the Alabama Development Office (ADO) — the state business recruitment agency — and then-Governor Jim Folsom put together one of the most lucrative incentive packages in history. They won, and Mercedes agreed to build its first North American plant in Vance, Alabama.

The Deal of the Century

The $250 million-plus package included $118 million in up-front subsidies and $55 million in potential tax breaks. These subsidies included sewer, water, and utility improvements; the purchase and development of the site; and annual funding for employee training.

In return, Mercedes promised to create 1,500 jobs directly and 14,285 jobs indirectly. Most of the indirect jobs were to come from nearby suppliers, but the deal did not require Mercedes to purchase supplies and services in-state.

The deal also required an overhaul of Alabama’s tax laws to allow the ADO to offer two types of incentive. The first was a corporate tax credit, which allows expanding companies to credit their taxes towards construction debt.

The ADO also established a “job development fee,” allowing a company to use the money their employees would pay in state personal income tax to repay their construction debts. Known as the “Mercedes Law,” this controversial provision had the potential to cause the state to lose millions of dollars in revenue. And since this new legislation could not be targeted to any one company, the break had to be offered to every business. By 1995, 86 other companies had received this benefit.

The Opposition Grows

As people learned more about the Mercedes deal, opposition grew. Republican gubernatorial candidate Fob James, who spoke out against the incentives, narrowly defeated Folsom in the elections. Other critics included small businesses, who feared that they would shoulder the tax burden created by these incentives geared towards larger manufacturers.

Organized labor also joined the chorus of opposition, concerned that other industries would consider layoffs to stay competitive. The Alabama Education Association (AEA) became a vocal critic, arguing the cut in corporate tax revenue would rob funds from the state’s constitutionally mandated education trust.

Analysis from the Bottom Up

Alabama Arise asked the Midwest Center for Labor Research (MCLR) to undertake an analysis of the incentive package offered to Mercedes, focusing on the hidden costs of the Mercedes deal. Key findings of their study included:

• Mercedes was the ultimate winner, by receiving a net tax break of $173 million, but only having to pay $65.8 million in state and local taxes. Additionally, if the company’s returns were not enough to pay the state loan of $42 million, the state would have to pay for it. Lastly, the plant faced no “clawback” provisions to penalize the company if it chose to leave the state;

• The people of Alabama would be the ultimate losers. The state had already lost $3 billion from various companies invoking the “Mercedes Law” — such losses would no doubt continue. Also, few good jobs would be gained and the average wage level in the state would not significantly increase;

• The Mercedes plant would create 1,500 direct jobs, but only 4,700 indirect jobs, since the plant could not (and would not) purchase in-state at the level ADO assumed in its cost-benefit analysis.

Financial Fallout

By February 1995, it was clear that the state would not be able to meet the obligation to issue the $42.6 million bond to Mercedes. The Governor tried to use funds set aside for education to pay the bond, but was stopped when the Educators Association threatened a lawsuit.

The Governor finally had to borrow from the State’s pension fund at an exorbitant rate to meet the bond obligation. It was also revealed in 1998 that Alabama may spend more to train workers for Mercedes and recent transplant Boeing than on elementary and secondary students. The state will spend $23 million picking up the tab to train workers and has agreed to spend $5 million a year for 20 years to operate the Mercedes training center.

Tags

Pronita Gupta

Pronita Gupta was the executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies from 1996 to 1998. She has since served in several positions, including the Deputy Director of the Women's Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor and as Special Assistant to the President for Labor and Workers at the Domestic Policy Council during the Biden administration.