This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 1, "Organizing for Dignity." Find more from that issue here.

Nov. 25, 1944

Richard Streb, a 19-year-old radar operator, was heading below to catch some sleep when he and a buddy heard the USS Essex’s big guns start to blast away in the sun-baked Pacific air. The aircraft carrier was under attack again.

They heard a bigger explosion. A wave of heat washed over them. Men shouted and ran past them. An officer tossed Streb and his buddy some gloves and told them to go clean up the flight deck. When they got there, they found the body parts of dead sailors. The intense heat had twisted one man’s right arm so that it pointed straight up. A New York Yankees cap hung from his outstretched fingers. A Japanese kamikaze pilot had crashed his plane into the Essex. Seventeen men, including the pilot, had died.

It was on that day that Richard Streb became an activist for peace.

Nov. 16, 1997

Navy veteran Richard Streb shouldered a black wooden coffin at the front of thousands of people marching onto Fort Benning. He and others had driven to Georgia to join in a demonstration marking the eighth anniversary of the assassination of six Jesuit priests, their cook and her daughter in El Salvador. Nineteen of the 27 military officers implicated in the killings were graduates of the U.S. Army’s School the Americas — a training facility at Fort Benning suspected of teaching Latin American soldiers the techniques of assassination and torture.

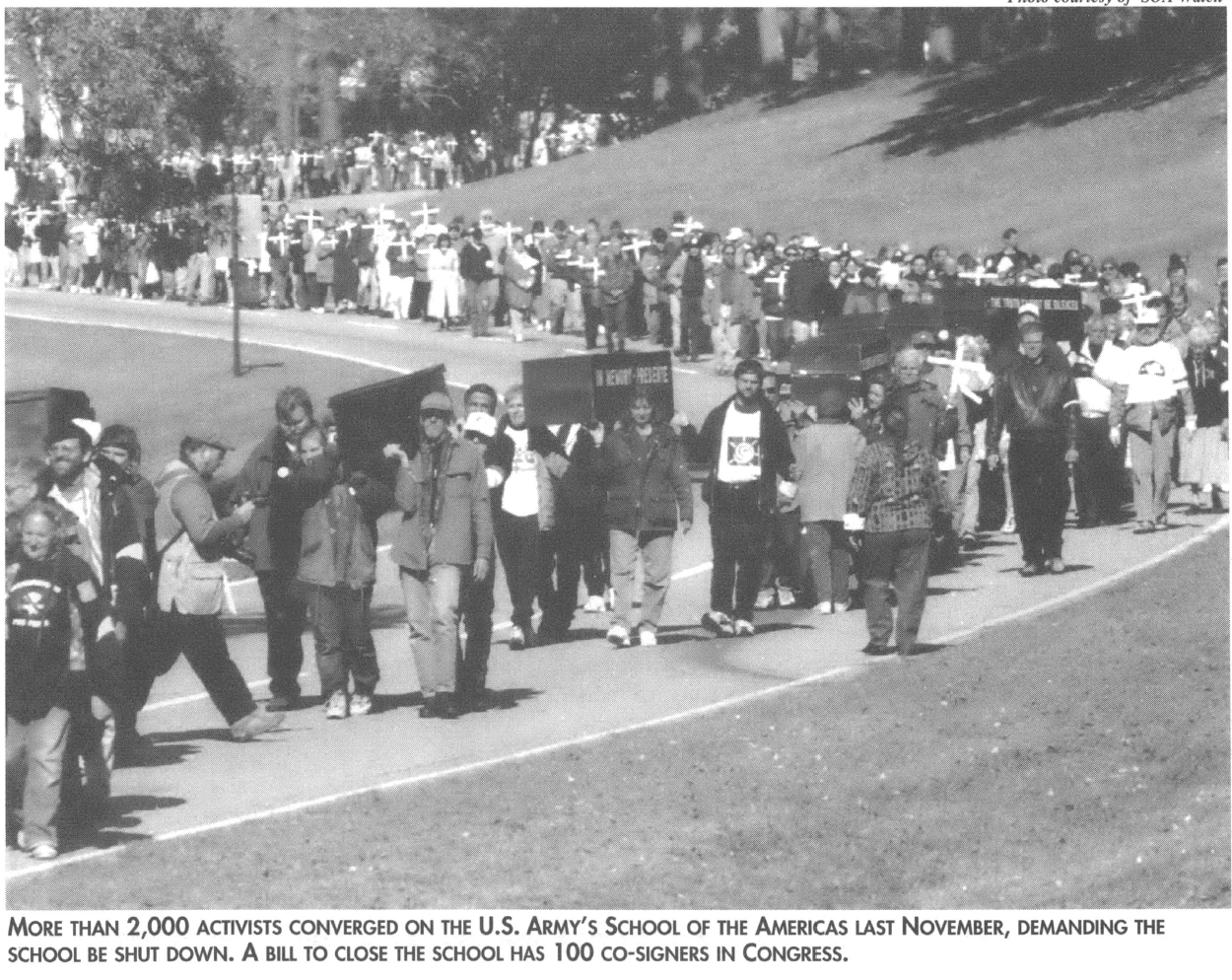

As many as 2,000 people — including veterans, nuns, clergy and students — joined the demonstration. They gathered outside Fort Benning for prayers and speeches. Then 601 of them marched onto the post, many carrying white crosses bearing the names of civilians believed to have been killed by graduates of the school.

After half a mile or so, they followed a bend in the road and came face to face with local and federal police. A voice on a bullhorn announced they were under arrest for trespassing. Officers searched and fingerprinted the marchers and gave written warnings to most. But they swore out criminal charges against 28 who had been warned during previous protests. One of them was Streb.

Three days later, Streb stood before a federal magistrate in Georgia and told of the battle stars he had earned in World War II and how his Navy experiences had led him to become a peace activist.

Then U.S. Magistrate William Slaughter announced his decision: He sentenced Streb and two other marchers to six months in prison and fines of $3,000 apiece.

The U.S. Army’s School of the Americas has trained almost 60,000 Latin American soldiers and officers since it was created after World War II. U.S. officials say its purpose is to fight communism, encourage democracy and instill professionalism in the Latin American military.

Critics call it the “School of Assassins,” saying the school trains its students in political murder, torture and other criminal techniques used to prop up U.S.-friendly dictators.

Graduates of the school include what Newsweek calls the region’s “most despicable military strongmen,” including former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, who is now serving a 40-year sentence for drug trafficking. Ten of the 12 Salvadoran military officers implicated in the 1981 El Mozote massacre — which killed 700-plus civilians — were School of the Americas graduates.

A 1992 Pentagon report found that teaching materials used at the school from 1982 to 1991 advocated murder, kidnapping and other crimes. The report said the manuals encouraged “motivation by fear, payment of bounties for enemy dead, false imprisonment, executions and the use of truth serum.” Rep. Joseph Kennedy, D-Mass., has introduced a bill that would close the school and now has more than 100 co-signers in Congress.

School defenders contend that its problems have been corrected and that reports of abuse have been exaggerated. “On a number of occasions, I was able to prevent a coup because I knew the people,” said Edwin Corr, a U.S. ambassador to several Latin American nations during the Reagan administration. “They had been to the School of the Americas, and I was able to use that as common ground.”

“You always hear about the horrible human rights violations by a few bad apples,” Corr added, “but you never hear about all the crimes that were prevented.”

A protest group, School of the Americas Watch, has been organizing opposition to the school since 1990. The group includes retired Maj. Joseph Blair, a Bronze Star winner and former instructor at the school. He believes the “few bad apples” defense doesn’t wash, and that the School of the Americas should be shut down.

“It’s time for SOA to drown in its own blood,” Blair said.

In court last November, Streb quoted Thomas Jefferson and talked about how his wartime service had changed his life. He hoped it might sway the magistrate. It didn’t. The federal courts slapped Streb and 24 others with the maximum prison sentence — six months.

The activists see this as a perversion of justice. “Justice is being turned upside down,” said the Rev. Kennon, one of the 31 arrested. “We will go to prison for walking in a funeral procession, while SOA killers and those who train them go free.”

Streb hates the thought of a cell door clanging behind him, but what concerns him most is losing time out of his life. He’s got things to do. “At my age,” Streb says, “I don’t want to waste six months.”

But he doesn’t regret his decision. When he got out of the Navy, he knew he wanted to work for peace. In the past few years, his time has been consumed by traveling around the United States to interview his old shipmates from the Essex. He hopes his book will provide a window to the suffering of war.

“If you want to have peace,” Streb says, “you have to be able to compromise and adjust. And there has to be greater equality. You can’t keep peace if people are hungry and starving.”

For more information on the School of the Americas, go online to the Columbus (Ga.) Ledger-Enquirer at http:lwww.l-e-o.com/ news/soaindex.htm, or contact SOA Watch at PO Box 3330, Columbus, GA 31903.

Massacre in Mexico: The SOA Connection

By Michael Steinberg, an investigative reporter based in Durham, NC.

The massacre of 45 unarmed civilian in Chiapas, Mexico, by paramilitary death squads on Dec. 22, 1997, brought the brutal fury of the region’s low intensity warfare to the world’s attention. Though local officials were arrested, and the governor of Chiapas and the federal interior minister were forced to resign, others have asked if the roots of this repression lie in the United States.

Mexican officers have become the largest national grouping trained at the School of the Americas since 1994, when Zapatista rebels rose up against the government. SOA admits that 153 Mexican soldiers and officers graduated in 1996. That number rose to 315 in 1997 — one-third of the graduating class, according to SOA Watch.

SOA training manuals have included torture and assassination as counterinsurgency techniques. A 1959 Mexican SOA grad, General Juan Lopez Ortiz, was sent into Chiapas after the January ’94 uprising. In the town of Ocosingo, troops under his command summarily executed five suspected Zapatistas. The troops tied the prisoners’ hands behind their backs before shooting them in the back of the head.

So far, SOA Watch has identified 13 Mexican SOA grads involved in southern Mexico’s low-intensity warfare. A number of them are suspected drug traffickers. The Mexican magazine Milenio recently identified five more Mexican SOA grads involved in this southern counterinsurgency campaign. Milenio named ’95 SOA grad Raul Gainez Segura as holding a position in Military Intelligence in Chiapas.

Yet more evidence of a connection comes from Guatemala. In early January of this year, the Mexican newspaper Cronica de Hoy identified two Guatemala Army SOA grads as suspected illegal arms traffickers in an operation originating in Guatemala City. The article described assault weapons, such as AK-47s used in the Acteal massacre, being loaded onto Mexican trucks.

Some Famous SOA Graduates

For $20 million each year, the School of the Americas trains 900-2,000 soldiers from Latin America and the Caribbean. Since 1946, the U.S. Army’s SOA has trained almost 60,000 Latin American leaders in “counterinsurgency.” Some of the school’s most notorious alumni:

ARGENTINA

Gen. Leopoldia Galtieri: President, 1981-82. Oversaw the last two years of junta rule when an estimated 30,000 suspected dissidents were tortured, disappeared and/or murdered.

BOLIVIA

Gen. Hugo Banzer Suarez: Dictator 1971-78. Took power through a bloody coup and developed the Banze Plan to silence outspoken members of the Church: the plan became a blueprint for repression throughout Latin America. Inducted into the U.S. Army School of the Americas Hall of Fame (SOA-HOF), 1988.

COLOMBIA

Gen. Luis Eduardo Roca and Gen. Jose Nelson Mejia: Colombian Army. In 1991, Generals Roca and Mejia — in thanking the U.S. Congress for $40.3 million in anti-narcotics aid — pledged $38.5 million to a counterinsurgency campaign in northeast Colombia, where narcotics are neither grown nor processed. Both SOA-HOF, 1991.

Lt. Col. Victor Bernal Castano: Was allowed to attend the SOA in 1992 to escape a criminal investigation of his role in the massacre of a peasant family.

EL SALVADOR

The U.N. Truth Commission Report on El Salvador, released in 1993, cited more than 60 Salvadoran officers for atrocities during the country’s civil war. More than two-thirds of those named were SOA alumni, including two of the three cited in the murder of Archbishop Romero, and 19 of 26 cited in a massacre of Jesuit priests.

Col. Jose Mario Godinez Castillo: Cited by Salvadoran Non-Governmental Human Rights Commission (NGHRC) for involvement in 1,051 summary executions, 129 tortures, 8 rapes — 1,288 total victims.

Col. Dionisio Ismael Machuca: Former director, National Police; former member of SOA cadre (Panama). Cited by NGHRC for involvement in 318 tortures, and 610 illegal detentions.

GUATEMALA

Gen. Manuel Antonio Callejas y Callejas: Under President Remeo Lucas Garcia, was senior intelligence officer in charge of choosing targets for assassination. SOA-HOF, 1988.

Gen. Hector Gramajo: Retired defense minister. Held key military and government positions: architect of government/military strategies that legalized military atrocities throughout the ’80s.

HAITI

Major Joseph-Michel Francois: Police chief, Haiti. Played a key role in the Haitian coup that ousted President Aristide. SOA trained Haitian soldiers prior to 1986, during the Duvalier dictatorship.

HONDURAS

Gen. Policarpio Paz Garcia: Dictator, 1980- 82.

Ruled during 100-150 disappearances. SOA-HOF, 1988.

PANAMA

Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega: Ex-president and CIA asset until ousted by United States. Now serving 40 years in U.S. prison for drug trafficking.

Information from CovertAction Quarterly, Newsweek, Washington Post and School of the Americas Watch.

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)