This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 1, "Organizing for Dignity." Find more from that issue here.

The authors would like to thank all of the individuals who took time out of their busy schedules for our interviews.

While welfare has never been the supportive system that many believed it could become, recent changes have sent a signal to millions of low-income families and children that government will not provide assistance through hard times.

The carefully-balanced budgets of welfare participants have been thrown into disarray. Welfare offices have become paperwork nightmares. The rhetoric of “work not welfare” blares on, despite the contradiction between the need to nurture young children and the sub-living wages available to welfare participants. In the face of this reality, those who care about the fate of the South’s and America’s poor are left with one question: What now?

If there is a bright spot in the chaos resulting from “welfare reform,” it is the energy of people who realize that real change will come from the people most affected by welfare policies. Looking across the southern landscape, we have found a blossoming grassroots effort to clip the claws of reform and to build a movement for true economic security. As Sandra Robertson of the Georgia Citizen’s Coalition on Hunger says, “People are ready to deal with this. We’ve had to take a few steps backwards, but we are building and organizing constituencies.”

In this report, we offer a glimpse of the issues, strategies, challenges and lessons that are key to understanding welfare reform organizing in the South.

Southern Strategies for Change

To many newcomers, welfare issues quickly get very technical. Experts start to talk about benefit formulas, work requirement percentages and other complicated policy questions. But the reality on the ground isn’t all that complex. In fact, organizers around the South routinely find their constituents facing common basic problems.

Welfare participants want better support from the state. They want social service agencies to respect their rights and their dignity. They have come to the conclusion that work without a living wage is often worse than no work at all.

And perhaps most importantly, they are asking the question government chooses to ignore: What is happening to those families leaving the rolls?

1. Demanding support, rights and dignity

Around the region, organizers and constituents are mobilizing to demand that policymakers provide support for families in need. To this end, communities want suspension of time limits, increased access to education, safe and affordable childcare and other kinds of support families need to make a real transition from poverty to economic independence.

The issue of education serves to highlight one of the internal inconsistencies in welfare reform: Policymakers claim that welfare reform will help lift families out of poverty, yet the changes they have made restrict the best way to get a job that pays a living wage—advanced education.

For many groups, access to education has become a main concern. Viola Washington, of the Louisiana Welfare Rights Organization, stresses the importance of legislation that was passed by Louisiana grassroots groups. Reversing the attitude of “work or else,” the new law will “hopefully allow welfare participants to attend college, despite the fact that attending college does not help the state meet its federally mandated work participation rates.”

Several chapters of the 2000-member Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC) have also identified “access to education for low-income Kentuckians and especially welfare participants” as one of their three main agenda items. As Virginian welfare participants asked, while lobbying a legislator in a state where welfare participants are barred from education activities while receiving assistance: “How could anyone get a job without a GED?”

The failure of policymakers to recognize that single mothers with children probably need more rather than less public assistance as they struggle to improve their education and job prospects is one of the many flaws in what has been called welfare reform.

When confronting policymakers, low-income community members are raising critical questions about the course of welfare reform. Mary Carey, a resident of public housing in Charlottesville, Virginia, put a Republican legislator on the spot. “I asked him, how are lawmakers gonna come to a solution so no one gets hurt? I knew him since he was a boy. Paul [the representative] already has his position—he’s got his income, his law firm, his family. I asked him ‘what about folks that don’t know in a year if they’ll have their family, or will they have to rob a bank to survive?’”

Other organizing efforts are targeting the administrative bodies in charge of social services. In those cases, community-based groups often find themselves fighting for what little rights welfare participants are afforded under the new laws or simply fighting to be treated with dignity.

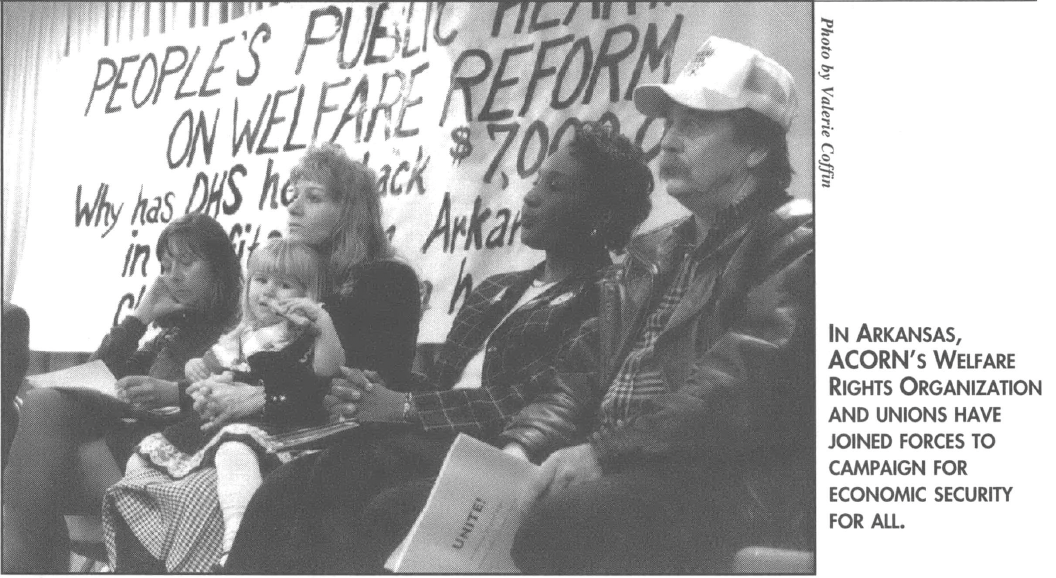

Mitch Klein of the Arkansas chapter of ACORN (Association of Communities Organized for Reform Now) described how the problems in his state mostly are focused on securing the rights that ACORN and allied community groups fought for at the state level. ACORN and other Arkansas groups managed to ensure that recent state welfare reform legislation provide up to $200 per child per month in child care, $175 per month in transportation assistance and $200 one-time in job search assistance. However, the legislation contains a loophole that allows this assistance to be paid out at social services’ discretion.

According to Klein, the money is not exactly flowing. At one point, only $94,000 out of $6 million had been spent on these needs. As ACORN put it, “if Joseph and Mary came to the Department of Human Services, they’d have to wait 30 days for help.” After exposing the problem, ACORN helped to get $1 million child care dollars into the hands of welfare participants in the first quarter of this year.

Arkansas agencies aren’t the only ones dragging their feet. In Virginia, authorities are reportedly distorting the rules to kick participants off welfare. The state’s law says that welfare participants are required to provide identifying information about their child’s other parent—a measure designed to help the state recover the cost of providing assistance from absent parents’ paychecks.

In reality, this provision has served as a tool to discourage applicants. “In case after case,” says Rebecca Rader of the Community Empowerment Organization of Virginia, “women were going in [to social services] and giving the three pieces of information and being told that they were ‘not giving enough information, we still can’t find him.’”

This tendency to discourage applicants arises from another fundamental flaw in the attempted reform of welfare: The federal law has given states an incentive to reduce caseloads without providing for adequate controls to make sure that families are leaving for good opportunities.

Often, welfare participants are merely looking to be treated with respect. Yvonka Weaver—who works 30 hours a week at Hardees, lives in transitional housing in Richmond, is raising a three-year- old boy and a four-month-old daughter and is enrolled in accounting classes at J. Sergeant Reynolds Community College—described what happened in her encounter with this policy.

While Weaver was participating in Virginia’s welfare program, she was called in for a meeting with a child support enforcement worker. According to Weaver, despite the fact that she provided all the information about her son’s father that was requested, the enforcement worker threatened her by saying, “you need to bring him [the father] physically to me—and if you don’t, I’m going to cut off all of your benefits.”

“At first I was scared that my benefits were going to get cancelled,” Weaver says, “that my child would go hungry, that I would be out on the streets with no medical benefits to care for my child.” Weaver adds, “But after I found out that the woman lied, I was angry. It’s wrong that they can do that to you.”

Unfortunately, this kind of disrespect and intimidation is likely to continue if left unchecked. The overall emphasis of changes in welfare policy have been to place virtually all of the responsibility for escaping poverty on the shoulders of welfare participants. For their part, social services workers who want to be helpful face overburdened caseloads and rapidly changing rules, forcing them to waste energy negotiating the system rather than helping families.

Participants are bound to their signed personal responsibility “contracts” and face severe penalties for failure to carry through on the deal. Yet, the lack of legal protections under the new system leaves welfare participants with little recourse when social services don’t hold up their end of the deal.

In such a climate, organizing has become one of the only solutions for participants in search of respect. “Where we are organized,” Klein says, “welfare recipients feel more comfortable demanding their rights and social services workers think twice before they sanction [welfare participants].”

2. Get a job? How about a living wage?

Even when welfare participants do find jobs, they’re finding it’s no ticket to economic security. Most work available for those coming off the rolls are entry-level positions that pay at or near the minimum wage. For example, in Virginia, studies have found that the average pay for welfare participants when they enter the job market is $5.50 an hour.

Realizing that families need far more to be self-sufficient, many southern groups have engaged in “living wage” campaigns. Some of these campaigns target a state or local minimum wage for an increase. Still others require a city or county and companies that contract with them to pay their workers a wage above the federal minimum wage ($5.15 per hour)—or a “living wage”—that would bring people above the poverty line.

There’s a lot of debate for what a living wage would pay. But these campaigns argue that anyone who works 40 hours a week should get a wage that supports basic needs.

One attempt to set a standard in the South came from the collaboration of the Washington, D.C.-based Wider Opportunities for Women and N.C. Equity, a women’s public policy organization in North Carolina. Among other findings, they concluded that in Greenville, North Carolina—a small metropolitan area in a rural section of the state—a single adult with a school-age child and a teenager would need to earn $8.08 per hour to meet their family’s basic needs. Their assessment of needs included: housing, child care, food, transportation, medical care, taxes, tax credits, miscellaneous items, and the size and age of families.

Community groups are using such findings to press for better pay. Encouraged by the fact that “a professional poll found that 75% of Georgians support an increase in the [state’s] minimum wage,” backers of an increase are working hard to build a base of support. The Georgia Citizen’s Coalition on Hunger recently helped pull together a meeting of more than 400 at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta to bolster an effort to increase the state’s minimum wage from $3.25 per hour to $6.24 per hour. Similarly, the North Carolina Hunger Network recently held a press conference to launch a campaign to raise the North Carolina minimum wage.

And if wages aren’t raised, some groups want to see public assistance help make up the difference. Welfare participants from the Louisiana Welfare Rights Organization have lobbied their Legislature—even “calling out from the gallery”—to pass a bill that allows welfare participants to keep up to $1,500 a month for the first six months they are working, without a cut in public assistance.

But economic security means more than wages, and many southern groups have identified a broader set of conditions needed for families to be self-sufficient. These are well-summarized in a petition circulated by the Tennessee-based Solutions to Issues of Concern to Knoxvillians (SICK), “We, the undersigned, believe that true welfare reform must include jobs with living wages, affordable health benefits, safe housing, quality child care and reliable transportation. All families deserve this.”

3. Assessing the damage, clipping the claws of reform

A number of organizations have also realized that, despite President Clinton’s cheerleading, there are major downsides to simply reducing the number of families “on the rolls.” Why are families leaving the roles? What is happening to them?

Lynice Williams—who as Director of North Carolina Fair Share is part of the state’s Welfare Reform Collaborative—has discovered that “many counties are [cutting rolls] based on sanctions.” Most of these sanction terminations have been for “being late or missing appointments” with social service workers, even though participants often had good reason.

Williams points out that for many southern welfare participants in rural areas, a trip to social services means more than personal responsibility—it means relying on the inexact science of buses and rides from friends.

But the bigger problem is that no one knows what is happening to welfare participants who leave the rolls under these circumstances. Many are too discouraged to try again for the average $217 per month in assistance that welfare recipients are eligible for in the state. What are the consequences?

The N.C. Welfare Reform Collaborative is working with many organizations throughout the state to conduct a survey to find out what has happened to families that no longer receive assistance. Sample survey questions include, “In the last 30 days, have you or a family member gone without enough food for a day or more because you did not have enough money? If yes, please explain.” Other questions ask for more detail about a family’s economic situations and any loss of benefits.

Using a different tactic, the Kentucky Youth Advocates helped sponsor a “listening tour,” traveling to videotape testimony from welfare participants about the problems they were encountering. Alabama Arise and the Alabama Organizing Project have used similar strategies. In Richmond, the Coalition for Virginians in Need has helped to circulate a survey of food pantries as an indirect monitor of the impact of reform.

Challenges and Solutions

As with other mobilizing efforts, welfare reform organizing in the South has its share of barriers and challenges. Many organizations are using a combination of familiar organizing techniques blended with new strategies to overcome these difficulties.

Day to day challenges

How can we get people to meetings? What about child care? With public transportation and affordable child care both being scarce, many organizations start with these basic problems.

Both the Monticello Area Community Action Agency (MACAA) in Charlottesville, Virginia, and SICK recruit middle class volunteers from local churches and other community organizations to be drivers.

Lea Alexander explains that for SICK in Tennessee, child care became part of a strategy for encouraging involvement in meetings. “We pay child care folks $7 an hour and try to hire low-income individuals as care providers.” SICK also proposed the idea of having participants rotate the child care responsibilities every 15 minutes during their meetings. Burdensome, maybe, but also crucial to building a base. After all, as Alexander states, “How do we keep individuals involved who we want to participate, while acknowledging that they are struggling with serious issues that affect their families' very survival?”

Fighting frustration, demoralization and intimidation

The constant lack of meaningful responses and blatant apathy from policymakers often discourage participants from becoming further involved. For example, during a Welfare Rights Organization (WRO) meeting in New Orleans with policymakers, “the welfare participants in the room found out

that some of the policymakers had not read the bill before they voted,” recounts Viola Washington, the group’s leader. WRO members were outraged . “It was difficult at best to move the conversation forward.”

WRO's solution was to used was to invite participants to come to the next meeting an hour before policymakers arrived—giving them a chance to vent their frustration and develop a strategy for the meeting.

Mary Carey, a welfare participant in Charlottesville, Virginia, felt a similar lack of concern when she attended an event to speak to state legislators. “They didn’t have the decency to show up. I kept saying, ‘What are we here for—to ride up and down the elevators?’—the representatives don’t care about poor people. They just say, ‘this money doesn’t go into AFDC, let’s build another road.’”

People on public assistance who choose to stand up for their rights often face the wrath of politicians seeking to preserve their “get-tough” image. Stephanye Goins, the former chair of SICK’s welfare reform committee and a former welfare participant, remembers a meeting with Tennessee’s state social services commissioner:

I was at the April 15th meeting and I was the main spokesperson. It was intimidating. She [the commissioner] started saying something about we can’t raise [welfare] costs because taxpayers wouldn’t like that. I had to bite my tongue not to tell her I was a taxpayer myself. Then, the director of the Knox City Department of Human Resources said that I shouldn’t be complaining and “if you would look past the end of your nose, you wouldn’t be in the situation you’re in.”

Such intimidation affects organizing. “When we go door to door,” says Lea Alexander of SICK, “we can’t say ‘have you been affected by welfare?’ because of the stigma associated with receiving public assistance.”

But there are creative solutions as well. Says Alexander: “The state calls Family First Participants ‘customers’—so we like to point out that the customer is always right!”

The Gospel Supper Club—A Healing Place, Inc., in Durham, North Carolina, is a spiritual development and social justice organization that helps people fight demoralization with faith. “They [welfare participants] have been so beat down and had such hard times,” says founder Alease Alston. “Those holes in the soul have to be emptied of garbage, healed and sealed.”

“We do workshops to deal with fear and internalized oppression from a spiritual healing perspective,” says Vernessa Taylor, a minister. “We help people hear God’s voice to get them to still themselves and come out of a state of chaos and gain focus.”

In addition to teaching economic literacy, Taylor says, “We do footwashings, laying of hands, intercessory prayer, preaching, political education, meditation, dancing, singing . . . spiritual development undergirds them so they can stand up, gather their thoughts, speak out in forums and change their lives.”

Both of these women know chaos. “We experienced the destabilization and oppression of welfare. It happened to me 25 years ago and it still impacts my family because my children were taken from me and placed in foster care,” Alston stated. “I did not know my rights and my responsibilities to shape my life. Those policymakers and decision-makers, they are not living what we experience. The best people to speak out are the people being impacted.”

Taylor serves on Durham County’s Work First Planning Committee. She made sure that people who went through the Club’s healing process were allowed to present their views. “As they heal themselves, they’ll be able to serve on these committees. Without healing and spiritual development, there is no lasting sense of community.”

Changing populations and unifying issues

Borders are often blurred when it comes to organizing the working poor and welfare participants. Rebecca Rader of the Community Empowerment Organization of Virginia found that organizing both segments is key: “Especially with time limits and sanctions, you recruit someone who is on welfare and the next month they might be off. Our rolls have decreased by 42 percent, so how do we keep the momentum up once people have moved off?”

But these challenges present an opportunity to bring people together. Welfare reform and the lack of a “living wage” have brought together labor organizations, working poor constituents and welfare reform groups. On December 10th—the 49th anniversary of the UN’s International Declaration of Human Rights—welfare reform organizations and labor organizations joined forces in demonstrations across the nation coordinated by the national organization Jobs with Justice.

In Georgia, the Human Rights Union, formerly the Welfare Rights Union, held a joint meeting with the Atlanta Central Labor Council at a public hearing where 250 welfare participants, union members and concerned community members showed up to testify. Tameka Wynn, a full-time volunteer for the Human Rights Union summed it up: “We see human rights violations in welfare reform. It’s not only about welfare rights, it’s every right—from fathers to children to grandparents.”

Bringing in resources

Every movement requires resources, whether it be snacks brought to meetings or money for a full-time organizer. Unfortunately, it is often difficult for organizing groups to get the funds they need to support their work. One solution is to find support among those affected. The Arkansas ACORN chapter has enlisted more than 2,000 welfare participants as members and has more than 1,000 members who pay their $5 monthly dues by bank draft.

Organizations are also finding ways to attract foundation support. Fifteen organizations have come together to form the Southern Organizing Cooperative. Many of the member organizations have welfare reform as a main issue. While the Cooperative is designed to help organizations learn from each other and also to plan joint strategies, a central focus of its work has been leveraging additional resources. Some of these resources include funds from major foundations less likely to fund individual organizing efforts.

Carryin’ On

In the face of seemingly unbeatable odds, people’s organizing efforts are responding to the challenges of welfare reform. These groups are taking the time to support their members and to build leadership among those affected. They are finding issues that cut across constituencies, bridging gaps with labor and community organizations.

And despite the odds, there are victories. Some groups are finding success in the new-found confidence of welfare participants, ready to stand up and demand rights and dignity. For many, this begins with being treated as human beings. As Lea Alexander says, “The most important thing we do when we go door-to-door is listen to people.”

Others are claiming victories in the halls of power. Some groups are demanding that officials attend their meetings and be held accountable. Others have successfully mobilized to reverse laws that punish the poor.

And perhaps most importantly, they are keeping the momentum for the next battle. “So many families and children are going to be negatively affected,” says Sandra Robertson in Georgia. “But we can turn it around, and we are ready to fight. I’ve got my boxing gloves on.”

What is Welfare Reform?

Welfare reform has evolved out of a series of federal, state and, in some cases, local policy changes. The main fact that holds true across almost all communities is that there is no longer any guarantee of cash support for poor families raising children. This is why you hear people say that “welfare as we know it” has ended. Most other issues vary depending on where a family lives. But odds are your community has some of the following provisions:

Time Limits: There are generally two time limits that apply to how long welfare participants can receive benefits. Basically, all families receiving cash welfare assistance face a 60 month lifetime limit, whether the months are all at once or spread out over time. State law usually provides a shorter limit. For example, in North Carolina most families can receive benefits for two years and then are ineligible for three years.

Work Requirements: Even while families are receiving assistance, many will be required to work. The exact number of hours required per week and whether any families are exempted for reasons such as having an infant at home vary from place to place. Many women are forced to take low-paying, often dangerous jobs without regard to whether safe, affordable child care is available. Personal Responsibility Contracts: These “contracts” are essentially orders from the state on what activities welfare participants are required to perform to receive assistance. In many states, welfare participants have to sign these papers before they can receive any cash benefits. Many welfare participants take the view that attending endless meetings and fulfilling other state-dictated criteria that seem irrelevant to their situation is not worth the $50 a week they receive in cash benefits.

Increased Use of Sanctions: As the guarantee of government assistance has ended, states have gained more freedom to use different and harsher sanctions—including complete termination of cash benefits. Welfare participants are sanctioned for missing meetings scheduled during working hours, even though they have received as little as two days’ notice.

Limits on Appeal Rights: While not all states have limited rights, they have gained the freedom to restrict participants’ appeals. Welfare participants do have rights and should consult with legal aid or other experts when they think they have been unfairly sanctioned or turned away from assistance. Welfare participants are missing out on support they legally deserve because they have been told that they have no rights, only responsibilities.

Increased State and Local Welfare Planning: This is what welfare reform is supposed to do best, return control back to local communities. Unfortunately, it has served in some areas to make it harder to keep track of the affects changes are having on families. Given that local southern governments have been less dedicated to supporting social services, local planning threatens to concentrate control of welfare policy in the hands of people whose agenda might not reflect the best interests of the community.

Caseload Reduction: Under federal law, states can receive “extra-credit” for reducing caseloads. But the caseload reduction rates often boasted by governors tell little about whether families are achieving economic independence, or whether they are off the rolls simply because they are unable to comply with rules that often are designed to discourage enrollment. Experts say the reduction of poverty and the promotion of child well-being are better barometers of change.

Region-Wide Welfare Organizing Initiatives

By Lenore Yarger

Southern Organizing Cooperative

The Organizing Cooperative is a fledgling group of 15 local organizations who are putting their heads together to improve the state of grassroots organizing in the region and to bring greater resources and fundraising ability to community action in the South. Currently, the cooperative is organizing a spring meeting on the hows and whys of popular political and economic education as it relates to grassroots organizing. The cooperative also plans to sponsor anti-racist training for its member groups. (Contact: Burt Lauderdale, (606) 878-2161)

Highlander Center

Last October the Highlander Center, together with Southerners on New Ground and the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, convened the “North-South Dialogue on Building a Poor People’s Movement.” The gathering provided a forum for participating groups to share strategies in organizing poor people around issues of welfare reform, low-wage work and homelessness. Currently the Highlander Center is compiling a mailing list of poor people’s organizations and a newsletter about the October conference. (Contact: Susan Williams, (423) 933-3443).

Children’s Defense Fund Black Community Crusade for Children

In January 1997, the Children’s Defense Fund Black Community Crusade for Children gathered 300 people in seven Southern states for a day and a half training session on states’ options for welfare reform under federal law. The gathering focused on legislative approaches to influence state law, as well as on community monitoring activities to track families who go off welfare rolls but not to work. (Contact: Oleta Garrett Fitzgerald, (601)-355-1213).

Center for Community Change

The Center for Community Change provides a handful of southern local groups with technical support and is currently developing a grants pool to support grassroots organizing around welfare reform issues. Once a month the center publishes the newsletter Organizing, which describes different reform campaigns and suggests ways for local groups to respond. Call to get on the list to receive the newsletter. (Contact: Leigh Dingerson, (202)-342-0594).

Jobs With Justice

In December, Jobs with Justice helped coordinate “Days of Action” across the nation in protest of the harm being done in the name of welfare reform. As part of these activities, they co-produced a four-page comic strip that illustrates the contradictions within welfare reform. Every group should find this resource helpful. Currently, Jobs with Justice staff are helping welfare reform-oriented groups strategize to expand activities to include organizing around living wage and other issues important to the working poor. (Contact: Mary Beth Maxwell, 202-434-1106)

Foundation for MidSouth The Foundation for MidSouth facilitates the local organizing of groups in Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi on issues of education, economic development and families and children. On Feb. 3 and 4, the foundation convened a regional meeting of community activists and state and local representatives. Using welfare reform as a starting point, the meeting planned to address services needed by poor people and develop strategy for future collective action, which could potentially involve reporting, mapping geographic data as well as planning other regional gatherings. (Contact: (601) 355-8167)

Fund for Southern Communities

The Fund for Southern Communities has responded with grant awards to two local groups working on welfare reform issues: the Georgia Urban/Rural Summit and the Georgia Citizens Coalition on Hunger. (Contact: (404) 876-4147)

Tags

Keith Ernst

Keith Ernst is an attorney for the Center for Responsible Lending, and a member of the editorial board of Southern Exposure. (2003)