This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 1, "Organizing for Dignity." Find more from that issue here.

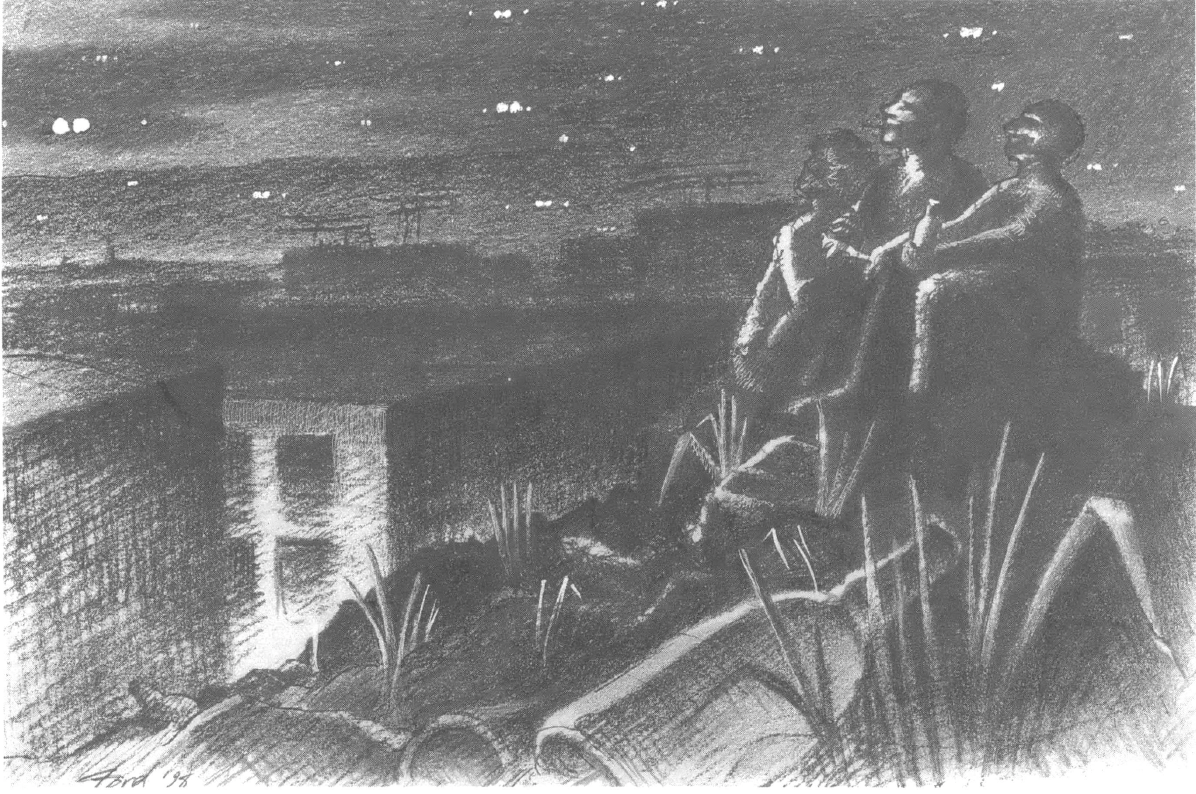

Now it was night. It was nights before Walton got caught, finally arrested, nights before he finally let our neighborhood fall to relief and old routine. We were waiting up here on our hill for warm Jincy, Walton’s lover, though Jacks and I didn’t mention her, didn’t even know we were waiting for her. Jacks and I had sat silent with Walton while the neighborhood brick shadows stretched down below us, turned to lamplit broken glass, took the chill off the bottles in our hands. Jincy. That afternoon, she had cut the kid loose, dropped him without a whisper, and now it was night, distant smoke in our throats, on our skin, only smells. Jacks and I had a straight view to those slow-motion pieces of light on horizon, other people flying places, planes so slow they should have dropped. We were only waiting, watching, next to Walton the poet, wanting Jincy as much as he did in that damp night air, not knowing our own wants.

Walton’s face only held enough cityglow and neon from Roo’s Liquor sign to show his big eyes near glassy watching nothing or everything, maybe watching the planelights even then. We couldn’t see National for the distant skyline, the pitch Navy Yards silhouette, Fort McNair, then Bolling Base, but Jacks and I knew the airport from the white lights crawling in and out. This hill we sat on was our hill, built off fallen stone and charred dust you still taste from a blazed-out slumrent, off jagged blocks of concrete and plasterboard and empty 40 bottles, and wreckage long covered over now by city smog and dirt, and brown, dead grass. The grass cover almost took out the fire smell, forgot the wreckage underneath, made it feel like we sat on a true piece of mountain. Jacks and I were always waiting up here for something we couldn’t explain. In the breezes, in an hour, somebody might say her name.

This Jincy was white, see, and from outside these blocks, and somehow Walton had spun the right words for her for some time. Couple of months at least the two of them were walking around. I’m white and she’s the whitest white I’ve seen, the inside of sunlight. Walton’s a brown. Jacks is pitch, watched him get blacker with his years. Not that this is a matter as much here. This might be a last place in the city where poor is the first color. Jincy wasn’t poor, she was so white.

It was getting loud down in the neighborhood with new night noise, car motors, shouts, door slam echoes. It was too cool for November, but Jacks and I weren’t cold yet—the drinks. Jacks the talent lit a cigarette with a swig of St. Ide’s under his tongue. He sat in night shadow, bull’s chest, bolt-upright back, mostly lost in the dark.

“Where do these people go?” he said. More flyers crept off the orange haze into deep night.

“Anywhere,” I said. “Buffalo.”

Walton wouldn’t make a noise. After awhile we couldn’t help but imagine hearing him breathe and sweat and shiver, and we did wonder, finally—wondered still without admitting wanting her—what a new dead heart used to feel like when we were just 19. Once before, couple of years before, Walton had tried to kill himself when he was cut loose. He took a shoplifted bic, disposable mind you, and bungled the job. Snapped the handle, cut his arm with the jagged plastic and barely broke skin. His poetry had failed him that time, too. Those lines he wove to get this Latino off the Heights into bed with him—he must’ve started believing his own rhyme. Wide-eyed, hard-shouldered thinker, always under love believing his own poetry. Magicians believing in magic ought to know better.

Jacks and I were caught up in the cityline, though, the only civilized view in the neighborhood, trying not to let the boy’s dead heart crowd out a few moments of contentment with the drinks and the view. Though Jacks and I knew better about this view. From here you could see the White House if you stood. We sat. Jacks always called it other people’s view, those monuments and lit memorials and dark museums, red rooftop lights to guide in the planes, hell even the planes. Jacks always said it was other people’s so we’d drop our cold empties and head to the street for refills or just to find home.

But this night with Walton was early still. Air traffic was heavy, we wanted to watch. We drank our false heat, with those slow horizon lights without sounds, and everything became quieter than it could be. For a moment, a whole minute, longer, we kept the quiet going. Jincy might come back. There was balance in the possibility of it, with those sharp white lights hanging mid-air out there, though Jacks and I knew better than to caring anymore about it. A deep black cloud ceiling started rolling in. The first short night breezes came up off the rooftops raising goosebumps we didn’t feel from inside.

“She stole my windows,” Walton finally said, and those quiet pearl lights that had swallowed us up spit us back out.

“What the hell you talking about, boy?” Jacks said.

“Jincy. She stole my windows.”

“Jesus, boy, you always got to speak in code?”

Sitting between them I didn’t want to be in the middle of this fight that was going to be about talking above your neighborhood. Jacks thought Walton’s poetics was just a way of the boy trying to be more than he was, of denying he was three-quarters black and dirt broke and no better than the rest of us. Headlights coming, Roo’s sign blinking split the damp shadows up the side of the hill, changed nothing up top or in the view. I knew Walton never was going to be more than neighborhood, but I didn’t want him to give up his words either.

“You lose your windows,” Walton said, “then you can understand.”

“What the hell, boy, you think I can’t get a damn metaphor or whatever? Give it up a little bit.” Jacks spoke each stale word on the verge of cough. “Give your damn mind a little peace.”

My grip went tight on the bottle, almost hot in my hand with unswallowed sips. This must’ve been my anger I was afraid, this grip, though I couldn’t tell which one of them I was angry at, couldn’t find a place to sit down my bottle. But Syl showed, I was grateful. She shouted up from the street at us, broke the feeling. “James Jackson, that you?” Syl shouted.

“Yeah,” Jacks yelled down to her, “come up here, Syl.”

“Beirut, you there, too?”

She should’ve noticed me first, because Jacks was almost invisible at night, but from the street the city lights must’ve shown on him more than me. People always notice him first when the two of us are together, even, for no reason, in hot daylight.

“Yeah,” I shouted down to Syl, “I’m here.” She had her hands on her hips, wearing her “Nubian Princess” shirt you could see even from up top the hill. Something silver in her ear held storelight from inside Roo’s. “Come up, Syl,” I said. “Yeah, come up.”

While Jacks and I watched her climbing up, hands and feet like cats’, Walton must’ve crawled away. Once Syl was up and sitting next to Jacks, I remember worrying about Walton for a moment at first, but there was something different about this time with him. He had some little fight in him, this time, with his standing up a little to Jacks, instead of just quit in him like the other times he was a brokenheart. I let go of him. Jacks and Syl and I drank together on the wet grass, just the three of us, and took in those lights up off the skyline that seemed to defy gravity more the more. The lights seemed slower and slower, impossibly slow to keep afloat. They seemed even to stop sometimes, matted on space.

Soon Syl started treating Jacks and me like celebrities, calling us her men and squeezing Jacks’ arm. Jacks knew Syl since she was 12, hanging on laundry line like circus wire three flights over street. That was before I was dropped here, though not much before. Jacks and I weren’t dealing but we weren’t on our way out either. We were good enough for Syl, though, that night. Maybe she liked us because Jacks and I had the reputation for coming up here every night and she thought we were heavy thinkers. Syl was an easy mark for Walton with the romance she sees into people whether it’s really there or not. Walton could sleep with her anytime he wanted. Maybe he already did. I was glad he slipped away because I could tell the way Syl was squeezing Jacks’s arm and fingering his neck that Jacks was feeling young a little, enough to let the drinks do the rest of his feeling for him. Syl with her cajoling was relaxing him, easing those trenches in his face even though there wasn’t enough light to see all his shadows loosen, see all his calm. We both felt calm with temporary Syl there. We let her occupy us, with Walton and that restlessness well gone.

“I’m shaving my head,” Syl said. Her curls were cropped tight already, but she had good curves to pull it off. When Roo’s sign blinked up, you could see her nipples pushing cold hard against her shirt.

“A Nubian princess’ got to do what she’s got to do,” Jacks said. Jacks was married once, but somebody left somebody and the story changed according to whether Jacks was on a drunk.

“She has to,” Syl said.

“Beirut, we’re on cash?” Jacks said to me.

“No,” I said, “all we got’s in these bottles.”

So we saved our warm sips, talking for long stretches in between, listening to Syl tell about walking the Heights all drunk or knitting her Kente cap or trying to get on with cleaning at one of the Smithsonians. She pointed at one of the long black shapes on the cityline, said that was the museum where her aunt worked who might be able to get her an application. Her gesture was our only reminder for awhile that the rest of the city was out there. She talked about Billy’s cats, creaks in her floors, smell of her mother’s hot bread, even about a younger Jimmy Jackson always pleading with her to let him catch her from the clothesline. Backfires and short horn bursts echoed up from the alley wide streets. The 295 traffic sent rumbles up to us, cracks like lightning, people driving over road joints. For awhile there was screaming like singing coming off a fire escape we could only see in shadow a block away. The neighborhood was speaking up as Syl spoke her stories. We even listened to the breezes snaking through the long grasses on top of our hill, whistling through our empties. We even heard the bell clanging on Roo’s Liquor door, everybody going in to get recharged. And all this, for awhile, lured us in like massage. With just the three of us on this hill, for awhile, the neighborhood background was strangely musical and peaceful and good, even the distant screaming seemed like opera song, the best buzz and peace we had in a long time. When the singing down a block stopped, there wasn’t a larger question anywhere.

Then, without a warning, Walton came out of the shadows, making us feel like we’d been avoiding something. Syl noticed him first. “Walton,” she said, her voice singing up her excitement at seeing him, “what’re you doing up here?” Walton sat next to me, opposite end as Syl, crossed his hard arms. Syl didn’t leave Jacks’s big arm, but she loosened her grip.

“I was up before, left for awhile,” Walton said, keeping his eyes out on the night sky.

“Where you been?” I asked him. Jacks was wondering, too, but wouldn’t ask.

“Writing,” Walton said in whisper.

“To Jincy?” I said, too quickly, without thought, without knowing I’d be wondering so quickly.

“The white one?” Syl said, more kindly than she could’ve.

“To everybody,” Walton said.

Jacks lit another cigarette, struck the match so hard it seemed the flame came from his finger tips. “Give it up, boy,” Jacks said. “Whoever ‘everybody’ is, they won’t be listening, especially to you.” ;

Everything peaceful left in a hurry. Jacks and Syl and I looked at our empties in hand like they might refill themselves at least by a swallow, give us a break from the silence Walton hung around our heads. The three of us started getting the cold shivers. I tried to break the quiet, tried to get Walton involved in our old conversations.

“Walton’s got an in, too,” I said. “You know, Walton, Syl’s got this aunt at Smithsonian. Is it that one, Syl?” I said, pointing to the distant black rectangle I thought she spotted out to us before.

“Yeah,” Syl was helping me, “Air and Space.”

“And Walton,” I said, “Walton has a cousin Derrick— Derron?—who’s in Baggage at National.”

“Really?” Syl said. “Walton, how’s your cousin get that job?”

“That’s a job,” Jacks said. “Baggage at National. Walton, you in with Derron?”

But Walton wasn’t answering, just staring at the white points of light stuck mid-sky, the red rooftop lights showing people where they left, and the billboards way out by 295 with their backs to us. That screaming down a block on the fire escape started up again, this time louder, a woman’s yells and cut more desperate, but her old iron stairwell was mostly in shadow from up where we were. Some storelight off the alley that held the escape blinked red on the old grit bricks, lit the escape a little, nothing more than black shade moving its arms and yelling, like she was yelling up to us. The yelling started echoing and bouncing, like it came from deep out of the sewers, through the manhole covers, off the rooftops, instead of from some person, still like it was meant for us. Jacks’s new cigarette smoke stuck in our lungs. We didn’t move. When you move, to help, the yelling disappears, always, by the time you’re there, out of breath heart banging out fear. We only were a little grateful for some neighborhood misery to distract us from our own damp quiet.

“That’s some dream,” Walton said, dropping in cold with his words. Might’ve been he meant the sky sights were a dream. I hoped through that shrill screaming down a block that’s how Syl and Jacks would take it. That screaming. I knew though Walton meant to put it on Syl for making cleaning third shift at a Smithsonian some big new prospect.

“Think baggage, boy,” Jacks said, reading Walton all the way.

A block off down that alley, somebody shined a flashlight on the screams, lit a woman. She went still. She was a black girl by herself wearing not a stitch, stuck on the escape two stories up facing us without a ladder to the street. She must’ve got high and had a window latch catch behind her after she climbed out. She tried to cover her chest up with her arms, cross her legs, turn away from her spotlight. Then she quit, stood there hands at her sides waiting.

“I’m cold,” Syl said. She was never wearing enough either, the temperature was dropping faster than it should with that roof of clouds rolled in over the glow. The drinks were wearing off, it could frost.

The fire escape girl leaned on an iron rail, exposed and naked, thin, given up on hiding anything, still waiting for what was next. “I’m really cold,” Syl said. With the clouds in, the sky was holding more orange citylight. Syl nuzzled herself into Jacks some more. It was hard to tell how old the black girl on the fire escape was from up on the hill—16, 17. She stood motionless, propped on that black rail, a frozen statue, from up here. We couldn’t help her staring past the flashlight, trying to see who lit her up bare.

She wasn’t real.

Somebody cut their flashlight and the naked black girl was gone. We braced a little for the screaming to start up again.

“Ready, Jacks?” I said.

The screaming didn’t begin back. Jacks looked straight ahead. Syl had her head down, moved a finger around the wet lip of her empty.

“Jacks, ready?” I said. I turned to Walton to tell him we would head, but in the soft orange light he was smiling, only catching some cold light off the city unless a flash from Roo’s sign. I wondered what gave him any right to be so smug, like he was putting it on all of us for being mere average sprawlers. Somewhere else I would’ve had more the right than him but I didn’t act it. I threw my empty over my shoulder. The bottle clinked, wouldn’t break on something behind us. I saw only what Jacks saw in Walton, then, this smug pretender sitting himself over us. I hated him like Jacks did.

“Let’s go, Jacks,” I said.

“Something’s wrong,” Jacks said without turning to me. I thought he meant with the naked girl at first, meant that some neighbor didn’t have a favor in mind for her, but she was already just deep purple memory, afterimage, breeze.

Then I realized that Jacks and Walton both knew something, that whatever Jacks was talking about was the same thing that Walton was smiling at. Walton wasn’t being all smug with his smile. He and Jacks were into something I didn’t know.

“What?” I said. “Syl, you—?”

“Beirut, hush it up,” Jacks said.

So we sat there and everything went coldly quiet, no rooftop breezes even, city sounds still, as if they were silent just for Jacks.

“Something’s wrong out there,” Jacks said again.

“I see it,” Walton said.

“Somebody give me a goddamned clue, please,” I said.

“Beirut,” Jacks said, “how many lights we count at most ever?”

Then I saw what they saw. One night two years before, it was high clear out and Jacks and I counted 41 planelights coming and going from National, hanging on the view above skyline. Usually we saw 18 or 20 planes at one time on regular nights, six, seven, less in fog. But this night, for a cold clouded night with the cityglow as strong as it gets, there were too many lights. “What?” I said. “How many are out? 45? 50?”

“I got 56,” Jacks said. He’d been counting through the screaming.

Walton had, too. “I got 62,” he said, gesturing off right toward Bethesda and Wheaton, “counting these off pattern up North.” Looking out north, he had the back of his head to us but I knew he was still smiling. I started counting pieces of light as fast as I could.

“There’s six more must be sitting out past Alexandria,” Jacks said, checking South.

“What’s going on?” Syl said like she’d been drifted off.

“It’s the planes, Syl,” Jacks said.

“What?”

“There’s too many.”

“Too many for what?”

“For National,” Jacks said. “Planes coming in but none putting down.”

“Seventy-one!” I said. “Christ, I got 71.”

“Seventy-four,” Walton said. He had turned behind us to look out East, which never had a view but black sprawl haze, but tonight had nine more shimmers hanging mid-air. “Eighty-three,” Walton said. “That’s 83.”

“Sky’s filling up,” Jacks said. “Everybody’s knocking, but nobody’s answering the door.”

“Why aren’t they landing them?” Syl asked.

“It’s holding patterns,” I said.

“Something’s wrong,” Jacks said, “at National.”

We watched the sky start to fill up with landing lights that wouldn’t be used to land, with new stars inching into view, crowding out the sky, picking up patterns in layers over the city, and way out into the sprawl, hanging just under the high roof of clouds and as low as a few hundred feet above ground, every height in between. Some of them circled slowly at heights low enough it seemed to graze the Monument, seemed ready to land on The Mall, clip the flags off The Hill. The first engine roars, still distant and too high, began to pull us in. There were silent patterns we couldn’t see, too, in the icy cloudbank and above, stretching up as far as we could imagine, everybody waiting for National to say okay, come on in.

“Let’s go,” Jacks said.

“What do you mean ‘let’s go’?” Syl said. “It’s beautiful.”

“Other people’s view,” Jacks said. “Let’s go.”

“It’s our view,” Syl said, “and it’s beautiful.”

“Aesthetics,” Walton said, trying to be beyond us, “balanced aesthetics.”

“Fools, two of you are fools,” Jacks said. “Beirut, you listen to this?” Jacks was tensing me, but he and Walton couldn’t both be in the know and be dead opposites, and Walton had already riled me, too.

“What happened at National?” said Syl. “How’s a view like this come up?”

“Who gives a damn?” Jacks said. “You’re all three suckers. Who gives one damn?” He struck a new match to ridicule us.

But I still wanted to know. Despite all the nights Jacks talked about recognizing the skyline for other people’s view, I still wanted to know what was on at National this night. The patterns for these planes were clogging up everything now, lights like pinpricks stuck on distant black, closer crisscross routes, even some visible landing gear down overhead and behind us. Some plane routes, those closest, lowest planes that expanded their patterns to over our hill and behind, were so low and close now we were starting to understand the speed in them for once, to feel the violence in the noise of their engines. Now we could understand the sheer force in the planes, how they flew so easily, and I wanted to know why everything was different tonight.

“I’m with Syl,” I said. “What the hell is on at National, I want to know, and what the hell’s so wrong in wondering?”

Jacks drew hard on his new cigarette, wouldn’t even acknowledge me with disgust.

“Brother Jackson here won’t let you think it’s your city, too, Walton said, “like you got some stake in it, is what it comes back to. Right, Brother Jackson?”

“No shit, boy,” Jacks said, “only without the sarcasm. You think you got stake in this town?”

“I know what’s on at National,” Walton said.

Jacks wouldn’t bite. Syl and I were dying to ask if Walton knew what he was talking about, but Syl—Jacks scared her off any more questions. I didn’t say a thing either. It was frost cold and I was hating Jacks too hard, hating him for being right, deep down I knew he was right.

“Bomb scares,” Walton whispered.

“What?” Jacks said.

“National has some bomb scares over it,” Walton said. Another smile broke out, lit up his eyes.

“Walton,” I said, “could be anything, could be—”

“It’s bomb scares,” said Walton.

“How is it bomb scares?” Syl said.

“O.K.,” Jacks said, “yeah, how is it bomb scares?”

A low flyer shook us for a second, the lowest plane yet, pulled rumbles behind it away off the rooftops toward National.

“Poetry in motion,” Walton said. Then he laughed.

Then it all made sense.

Walton, brokenheart loverboy from the bottom of the hill, had sent one last poem to dear whiter-than-white Jincy, with a few phone calls shook the stars clean out of the sky for her.

“Too many to count,” Jacks whispered, his face like he was eyeing the lights out of focus, letting in the dream, “too many now.”

Another low flyer scared us off our thoughts. The roars faded, boomed against each other down in the streets. Other planes flew closer. Syl shivered. The city was fireworks with the glimmers.

“That’s one lucky white girl,” Syl said.

“It’s to everyone,” Walton said. “Not just Jincy.”

I sat next to plenty of thugs, dealers, users, knock and enter types in that neighborhood, but I was never having trouble swallowing like I was there next to Walton. He was nothing more than common crime with this stunt, except he was everything more, too, poet pretender, street poor black, governor of the town at the same time.

“Too many lights,” Jacks said again, still a little lost from us, like the planes were flying around inside his head instead of all over the city.

“How do you like it, Brother Jackson?” Walton said. “How do you like my poem?”

The air was frozen sharp. We were bracing for another plane to shake the neighborhood. Jimmy Jackson’s brow doubled creases with the prospect of Walton being the true author of it all.

“You run out of paper?” Jacks said.

“You like it?” Walton said again.

Jacks tossed away his last butt still a little lit. “Yeah,” he said, starting up a deep grin, “I do like it. I like it much better, now that I know who it’s by.”

Then, around the four of us, our hill started filling up.

Hard engine rushes carrying through alleys, landing lights dissolving street shadows, these planes shaking sky just above drew people out of Roo’s and broken window panes. Somebody said National was on T.V. with its bomb scares. Everybody wanted to come up to see it, see the glitter pasted around the sky, feel the hill shift under engine shock. Everybody wanted to see what happened when the rest of the world had to just stop and wait, fly in circles, pray for some ground. Everybody wanted to see who did it, see how it is that one of us could have this kind of effect on scenery. Eventually the planes even stirred the old hard use out of their cracks, still holding their empty broken car antennae pipes like Teddy Bears.

We all sat on the hillside, a few dozen at first, then soon a hundred or two, taking turns congratulating Walton with back slaps and jibes and murmuring at moving sky, and Jacks laughing all the time his old thick smoker’s laughs. We knew the poem for Jincy wasn’t just from Walton. He meant to show her from the rest of us, too, all of us there on our hill. We didn’t know quite what to do with that kind of knowledge. Later, not that night, later we’d be a little scared we ought to do something with it.

All of a sudden somebody said Roo’s Liquor lights were out, and they were, which meant Roo was closed already, at nine-thirty, that even Roo was watching the stark lights crisscross near collide somewhere on the crowded hill with us. “You got some audience, Walton,” Syl said to him softly. Even Roo was out here in the cold now, watching the new pinpricks blink into view, and none of these new flashes in the full sky could land. We all went quiet. Some new peace was coating us.

Then this came, at once, immediate, without a warning.

Heavy helicopter roars, pounding down on the grasses, hard winds from the copter blades blowing away sound. The machine hovered for a moment, put us under the spotlight, exposed us all. Wind burnt our skin, sent the cold through bone. Syl, Jacks, me, Walton, all the rest of us on our hill, we squinted away the light, covered ourselves hoping for God, then lowered our arms, stared into the hot light. My hands were sharp white, so were everyone’s. Then, just as fast, the spotlight rose and the helicopter was gone, ripping up sky behind it. Walton laughed. It started to snow. The snow wet our faces and hands, got in our eyes, we were looking up, still seeing rings from the helicopter light. We’d re-routed half the air traffic on the East Coast and now it was snowing.

Jimmy Jackson stood up, alone, unnatural, the bull up on his hind legs, stood for the first time in forever, like that night had been forever, his bones cracking together. He pulled Syl up, too, stretched his arms out after she was up. Only his stretching pulled this old piece of memory from a buzz or a night on the way to one, some moments and a lost view of Jimmy stretching that I once saw. I remembered first walking the alley, looking up, seeing a black girl sitting in shadow on her fire escape. She had her dress on then, silent, nothing to think of. She smoked some joint, watched over the rooftops in the direction of our hill. I smelled her joint down in the street. The buildings split, I glanced up a block. There was Jimmy Jackson, standing, stretching then too, arms out, waving, reaching for air, making shadowy snow angels in Roo’s empty liquor lights, empty black air. Red neon blinked out, and Jimmy Jackson was gone, then back, then gone, black snow angel, top heavy for a moment, then nothing, just black, only Roo’s Liquor lights giving him shape. I didn’t look back to the black girl, went to drink away what I saw, lost Jimmy in the buildings as I scuffed. She might’ve seen him for a moment—just a flicker, just a ghost, his own angel.

It was gray snowing now on our hill. Jimmy Jackson stood still with Roo’s neon out, stood against orange city sky dark solid as a monument. Syl swayed, Jimmy steadied her. It was quiet. Walton’s poem was clearing itself up. Shimmers roamed into black, disappeared. I was dead cold. I thought about them finding me the next day under a warm coat of white snow. I stared up into the flakes, swirling gray, lost all point of ground, and forgot where I was.