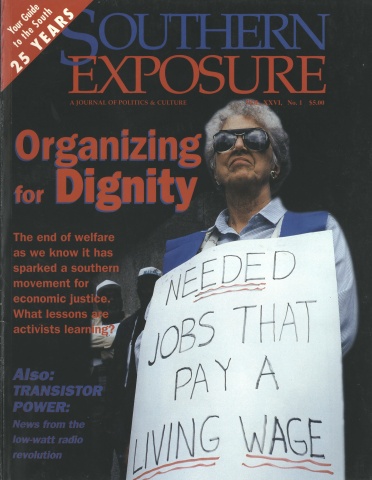

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 1, "Organizing for Dignity." Find more from that issue here.

In a per-dawn raid last fall in the middle-class Tampa suburb of Temple Terrace, Florida, dozens of federal and multi-jurisdictional agents — some armed with laser-sighted machine guns — converged on a quiet home, rousted its occupants from sleep and held them at gunpoint while electronic equipment worth thousands of dollars was loaded into a waiting van. It was a carefully staged swat team operation. Neighbors had been quietly warned to stay indoors and the media had been tipped off. As a government helicopter whirred overhead, television cameras recorded a domestic scene which, in past years, had been known for the Christmas lights that Doug Brewer strung on his ham radio antenna.

Stolen equipment? A drug bust? Neither. The Florida couple’s crime was the operation of a low-powered unlicensed community radio station, and their failure to pay a $1,000 fine previously levied by the Federal Communications Commission.

It all started innocently enough, says Brewer. One Christmas he began broadcasting Christmas music to drivers visiting his lights. But soon Brewer’s biker-rock “Party Pirate” station was broadcasting full time, and he was sporting a shirt that read, “License? We don’t need no stinking license.”

Only weeks before the raid, in a story about Brewer’s station in the Wall Street Journal, an FCC agent had vowed, “Sooner or later, I’ll nail him.”

Yet Brewer and his wife, Karen, were only one of three such operations conducted by federal agents against unlicensed broadcasters in the Tampa area — that same night. Further, the three represented only a portion of the nine or 10 unlicensed stations operating in the Tampa area. Across the state in the Miami area, insiders estimate there are as many as 40 such stations.

But low-watt radio is not just a Florida phenomenon. In cities across the South and across the country — from Richmond to Memphis, Houston, San Francisco, Minneapolis, Boston, Philadelphia and Kansas City — hundreds of Americans have taken to the airwaves without FCC sanction.

Quite simply, the nation is experiencing a near-revolution of unlicensed broadcasting. Driving this upheaval is the belief that public radio has failed, frustration with the emergence of megamedia monopolies, the availability of inexpensive micro broadcasting equipment — and, perhaps, the idea that radio, like speech, should be free.

A Micro Revolution

Pirate Radio, Free Radio, Micro-broadcasting — the term depends upon who is speaking. The FCC still clings to the outdated “pirate” label, while the National Association of Broadcasters has coined “broadcast bandits” — suggesting that these shoe string broadcasters are stealing directly from the pockets of the rich and powerful NAB members.

“We’re not pirates,” insists Willie One Blood, one of approximately 75 DJs on the unlicensed, 24-hour-a-day, seven-days- a-week station Kind Radio in San Marcos, Texas. “It’s a matter of free speech.”

The sentiment is expressed frequently by those seeking change in FCC regulations, and is one that strikes at the heart of important questions: Is the FCC’s mandate to regulate “in the public interest” best served by media conglomerates, or can small community-based volunteers better serve a community? Do low-powered stations have a free-speech right to the airwaves? Should they at least be afforded a small slice of the spectrum pie?

The station in San Marcos illustrates the potential of low-powered, community broadcasting. A couple of years ago the chamber of commerce there began exploring ways of getting a radio station for their community. Located half way between Austin and San Antonio, the town of approximately 50,000 people had for years been “served” by stations from the nearby cities. But in early 1997 the chamber decided that the idea was simply too expensive.

Meanwhile, the publishers of a local alternative newspaper, which had gained notoriety for winning a Supreme Court victory against the local university, were searching for yet another alternative. They settled on radio. In March 1997, members of the Hays County Guardian started Kind Radio and were soon transmitting to the community — 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Today the nonprofit, non-commercial station offers more programs than any microbroadcast station in the country, all with volunteers, donated equipment and 30 watts of power. Although programming is open to everyone in the community, there are a few rules: no obscenity, no pornography, no advertising and no selling.

“The biggest thing is to include all the community,” says Zeal Stefanoff, one of the organizers. “I think people here are beginning to really understand that free speech is more than just some words in the Constitution. We’ve had a county judge on the air. We covered the police elections, the marijuana initiative. We have a news show every day from 10 a.m. until noon.”

Of course, not everyone in the community is happy with the brand of programming offered by Kind Radio’s assorted crew of environmentalists, marijuana supporters and social activists. Stefanoff says there has been some harassment from local governmental agencies. But even that may be changing. In October 1997, a jury found Joe Ptak, director of the station, not guilty of ordinance violations filed against him by the City of San Marcos.

“It’s like we’ve got the only baseball in town,” says Stefanoff, “so even if everyone doesn’t like us they still send us their public service announcements.”

Nor is non-commercial, community radio a radical idea. In many countries, such as Japan, Italy and Canada, low-powered, non-commercial, even unlicensed, broadcasting is quite legal. Not only does Canadian law give priority to nonprofit community stations — it requires only a three-page application. In Japan Sony sells a complete, low-powered community broadcasting set.

Indeed, until the late ’70s, the FCC licensed Class D, 10-watt FM stations for non-commercial, educational purposes. But in 1978 the agency discontinued the practice, setting the lower transmitting power limit at 100 watts. The move extended the range of these stations, but lowered the number of potential locations on the spectrum. It was based on the philosophy that fewer, more powerful stations are preferable to numerous low-powered ones.

Somewhat surprisingly, the action had the support of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which saw it as a chance to increase not only its transmitting power but the professionalism of National Public Radio. But today, many critics claim that public radio, absorbed in seeking ever-larger funding, has lost its vitality and sold itself to the largest corporate bidders. They argue that public radio does not adequately represent the community.

Within an atmosphere of dwindling community programming, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 prompted a glut of media mergers and acquisitions. The heavily-lobbied deregulation bill loosened the FCC multiple-ownership rules and allowed for the wholesale acquisition of local stations.

On Feb. 7, 1997, the National Association of Broadcasters filed comments with the FCC asking the commission to “make substantial changes to its ownership rules in light of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and the breathtaking transformation of the local media marketplace.”

One month later, the FCC did so, eliminating the caps on the number of broadcast stations that might be owned or controlled by a single entity and revising local ownership rules to allow a company to own more stations within a market.

Not surprisingly, the industry had anticipated the move. In 1995 radio mergers and acquisitions amounted to approximately $70 million. By the end of 1996, the figure had jumped to more than $13 billion. Even those within the industry admit that the airwaves are now dominated by a handful of mega-corporations.

Low-Watt vs. Big Guns

Most of those involved in the free radio movement date its beginnings to the advent of WTRA Radio in Springfield, Illinois. In 1988, Mbanna Kantako, a blind former disk jockey, began broadcasting with a one-watt transmitter from his apartment in the predominantly black Hay Homes public housing project. As a member of the Tenants Rights Association, Kantako had been seeking a means of reaching those in the project. Because of his blindness and his background, radio was the perfect forum.

In 1989 the FCC fined Kantako $750 for broadcasting without a license. Kantako appealed the fine citing First and 14th Amendment rights. He also asked the court to appoint an attorney to represent him. But the federal court, ruling that the case was a civil matter, refused Kantako an attorney and upheld the fine. Kantako refused to pay the fine and continued broadcasting, expanding his schedule to 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although Kantako eventually decided not to challenge the FCC in court, the Committee for Democratic Communications of the National Lawyers Guild had prepared a set of briefs and arguments for his case.

“The committee was the result of discussions of the international participants in the McBride Roundtable several years ago,” says NLG attorney Louis Hiken. “The complaint was that all the world news comes from London, Tokyo, New York and so forth. To get local news is virtually impossible because of the monopoly in the media.”

“Micro radio is a natural for that. In fact, micro radio is one of the few means available to underdeveloped countries around the world that don’t have access to the millions of dollars necessary to establish large reporting systems. For $1,000 someone can set up a station in their own community.”

With their unused brief in hand, the NLG was ready for a new microradio client, and they soon found one, in the home of the original Free Speech Movement, Berkeley, California.

In 1993, radio engineer Stephen Dunifer had begun broadcasting on the FM band, packing his equipment into a backpack and hiking into the Berkeley hills to avoid the FCC. But in November of that year the FCC issued fines against Dunifer and in 1994 asked the court for an injunction against his broadcasts. Dunifer’s response has become a catch phrase of the free radio movement.

“Kiss my Bill of Rights,” Dunifer told the FCC.

Dunifer also began manufacturing and selling low-power transmitter kits and accessories and providing technical expertise, not only in the U.S., but worldwide.

In classic Catch-22 arguments, the FCC told the court that Dunifer should have applied for a license and asked for a waiver of the 100-watt minimum rule, although the agency has yet to grant such a waiver to a microbroadcaster. They also argued that while the court had the jurisdiction to issue an injunction, it did not have the jurisdiction to hear the constitutional questions raised.

But in 1995, Federal Judge Claudia Wilkens stunned the broadcasting world by denying the FCC’s motion for an injunction, allowing Dunifer to continue his broadcasts. It was the first such denial in the agency’s long history.

Soon, microbroadcasters, encouraged by the court’s decision, were sprouting like Mao’s 100 flowers. “Communities have a lot to gain,” says Dunifer. “Microbroadcasting can give them a voice they would not otherwise have, a voice that will reflect their community interests, not that of a remote corporation.”

From his San Francisco office, Hiken argues that the FCC has consistently tried to avoid any litigation that will address the constitutional issues.

“The FCC has spent the last three or four years trying to avoid a hearing on the merits of the case, on the constitutionality of prohibiting low-power broadcasting, on whether the FCC frequency allocations are based on the public interest, on whether they’re observing the least-wattage rule and employing new technologies. At some time they’re going to have to explain why giving to corporate interests is in the public interest,” he says.

It is also possible that the FCC has begun to tailor its enforcements against microbroadcasters in order to argue their cases to friendlier courts, which they have found in Florida and Minnesota.

On Aug. 24, 1997, the FCC won a summary judgment against Lonnie Kobres, a Tampa microbroadcaster whose equipment they had seized in March 1996. While Kobres had challenged the FCC’s authority to regulate his broadcast operation and the seizure of his equipment, District Judge Steven D. Merryday denied his claim to the equipment and granted the government’s motion for summary judgment. In a similar case in Minneapolis, the FCC news release stated, “. . . the Court agreed with the Government’s argument that the District Court does not have subject matter jurisdiction to consider the constitutionality of the FCC rules.”

The industry was delighted with the ruling. NAB President and CEO Edward O. Fritts told the press, “We are delighted that federal authorities have stepped up enforcement against pirate radio stations. The NAB Radio Board in June asked for the FCC to focus more attention on the growing number of unlicensed stations. We commend the commission for sending a strong message to broadcast bandits that their illegal activities will not be tolerated.”

But the NAB’s delight was to be short-lived. On Nov. 12, 1997, Federal Judge Claudia Wilken upheld the court’s jurisdiction on the constitutional question of FCC regulations prohibiting microbroadcasters. She denied, without prejudice, the FCC’s motion for summary judgment in Dunifer’s case and asked for further briefing on the constitutional question.

In her ruling, Judge Wilken dismissed the recent Minnesota decision, saying, “. . . a single district court case from another circuit is slim authority on which to base this decision.”

Again the NAB responded saying, “We are extremely disappointed with yet another delay in a case that was argued 19 months ago. Pirate radio stations are illegal and should be put out of business.”

A few days after Wilken’s decision, on Nov. 19, the FCC staged the Tampa raids.

Speech for Cheap

David vs. Goliah politics aren’t all that has fueled the microbroadcasting movement. Low-watt is popular because it’s cheap. The availability of reliable, low-cost transmitters means that an individual with $500 in his or her pocket and some common household electronics can start broadcasting, reaching an audience within a radius of perhaps five miles, perfectly adequate for most communities or small towns.

As Hiken stated in his brief to the court, “The historical significance of micro radio lies precisely in the fact that average citizens can now have access to the airwaves to communicate with their neighbors.”

Andrew Yoder, who has written a couple of books about pirate radio and has been the recipient of a nocturnal visit by FCC agents, says there are five or six major suppliers of low-power FM transmitters, including Free Radio Berkeley and Brewer’s company in Florida. While American suppliers cannot sell a completed FM transmitter to an unlicensed station, it is legal to sell “kits,” which may involve merely soldering a few wires together.

Of course the Internet is a goldmine of information about microbroadcasting, including hardware suppliers, information on how to start a station, pirate/free radio Web sites, bulletin boards and chat groups. There is even a wealth of technical information, such as electronic schematics and antenna designs.

Anticipating more micro radio cases across the country, the NLG has posted copies of their motions, pleadings and research on the Internet — all readily available to the nation’s more crusading attorneys. “We didn’t want other attorneys to have to re-invent the wheel,” says Fliken.

Room on the Dial

Like free speech, the free radio movement is one of those traditional issues capable of igniting the passions of a cross-section of the American public, attracting proponents across the political dial.

For two years Kobres, whose home near Tampa was also raided in the early-morning hours of Nov. 16, had been transmitting religious and right-wing political programs over the FM band.

“All I ever did was rebroadcast. All that information was on the satellite or the Internet. I just made it possible for people to get it on their FM radio,” Kobres says. “That’s the whole reason why they hit me. I’m not going to call it anti-government. We’re pro-government, pro-truth, pro-justice, but they’re perverting our society.”

“My wife and I awoke in absolute horror,” Kobres adds. “A helicopter was hovering over our house. They came to the door with a battering ram. I didn’t serve in the military to be subjected to this sort of thing.”

Kobres says that federal agents seized $25,000 worth of equipment and charged him with 14 criminal counts, each carrying a maximum penalty of 28 years in jail and a $200,000 fine. Serious penalties, but for first-time, low-profile offenders, the FCC currently seems to be following a policy of warnings, fines and equipment confiscation in its attempts to control the situation.

As to how many unlicensed broadcasters are operating in the U. S., it’s anyone’s guess. David Fiske, media relations spokesman for the FCC, says the agency doesn’t really have any idea; neither can the agency provide statistics on the number of FCC actions against microbroadcasters. “We don’t keep numbers,” says Fiske. “We operate on a case-by-case basis. I suppose someone could count them up.”

Strange for an agency that has dedicated an entire section of its Web site to “Low Power Broadcast Radio Stations,” complete with dire warnings of penalties and an explanation of the two relevant Supreme Court decisions concerning the constitutional question. The FCC does admit, however, that it receives 13,000 requests per year regarding starting a low-power radio station.

Yoder estimates that there are at least 100 unlicensed stations that broadcast on a regular basis. “It’s pretty much everywhere in the country,” he says. “But the stations in the rural areas don’t get much press.”

Other than the fact that they’re unlicensed, the FCC raises other objections in its battle against microbroadcasting. For instance, it often states that microbroadcasters interfere with legal stations. But in fact, evidence of actual cases of interference by microbroadcasters is hard to find. A 1994 Freedom of Information request revealed that the FCC possessed no written complaints over the alleged interference problems caused by Free Radio Berkeley. Faced with a scarcity of real complaints, the FCC encouraged members of the NAB to help identify unlicensed operators in their area.

The agency also claims that it is simply not practical to license low-power transmitters. But Yoder finds this hypocritical. ‘They’re licensing translator stations. Most of them are under 100 watts. The FCC is simply trying to fill all the space that’s out there.”

Low-watt advocates point out that, given the FCC’s mandate to regulate in the public interest and the fact that the broadcast spectrum is limited, the courts should reserve some right for a community to truly control its own airwaves.

In his brief to the court, Hiken defined what is at stake: “If there is irreparable harm to be found in this case, it is the ongoing policy of the FCC to license only the rich, and a handful of educational institutions, that creates such harm. Technology currently exists to allow thousands of Americans to have access to the airwaves in ways that could assure their democratic use and a meaningful voice in the democratic process.

“Instead, the FCC has created a system whereby the public listens, and the elite broadcast.”

Tags

Ron Holmes

Ron Holmes writes for Urban Tulsa magazine and other publications. (1998)