Digging for Roots

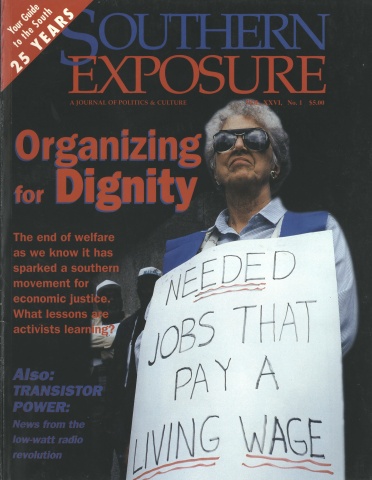

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 26 No. 1, "Organizing for Dignity." Find more from that issue here.

Wise, Va. — U.S. 23, just past Jenkins, Kentucky, is under ominous construction, and the road cut looms so high that the colossal limestone highwall looks like a mammoth archeological dig.

The gray rock matches the gray skies and the gray misty mountains, the way Appalachia always looks in the winter, like a gauzy web that cocoons natives but induces claustrophobia to visitors. I was on my way to Clinch Valley College, a four-year school that has accidentally become an international phenomenon as the nerve center of Melungeons — a group of people in remote outreaches of Appalachia who have been forgotten for years but who are now flourishing on the newly plowed ground of the Internet.

The common explanation is that Melungeons are a mix of whites, Africans and Native Americans who have lived in Appalachia. That definition was challenged about 10 years ago by Brent Kennedy, a chancellor at the college who believes that Melungeons have a more important place in history — the first peaceful mixing of Europeans, Africans, Native Americans and other races in America and possible descendants of Turkish seafarers.

Since then, Melungeons have exploded on the scene to claim their identity. Kennedy’s path-breaking book, The Melungeons: Resurrection of a Proud People, has sold more than 12,000 copies. A dozen Web pages have popped up on the Internet, a computerized e-mail list serves hundreds and more than 600 people gathered last summer in Kentucky for a Melungeon “First Union” — when initial planners thought they would be lucky if 50 showed up.

But who the Melungeons are and how they came to be in Appalachia is an unraveling story.

I ran into Brent Kennedy almost immediately after pulling onto the Clinch Valley campus. I stuck out my hand, and he shook it. But that was just an excuse to pull me forward so he could feel for an “Anatolian bump” on my head — a hallmark of Melungeon ancestry.

In the past, Melungeons’ dark features gave them a distinctive appearance, with olive skin, dark hair and piercing blue eyes amid a sea of Scottish-Irish immigrants. Other physical features, such as an “Anatolian bump” on their heads, Asian eye folds and shovel-shaped teeth, were distinctive markers for Melungeons.

He rummaged through my hair with medical efficiency. He didn’t find a bump but was undeterred. I definitely had Asian eye folds.

“I would check you for shovel-shaped teeth if I weren’t getting over the flu,” Kennedy said, and I was thus anointed as a Possible Melungeon.

filled and good-natured that it’s hard to tell at first whether these people are serious. They are.

Melungeons have been known in the region for centuries. But the new Melungeon researchers are dead-set on defining what it means to be Appalachian, and they aren’t relying on traditional explanations that Appalachians derive from Scottish and Irish heritage.

Kennedy started questioning the Scottish-Irish explanation when he became ill with something his doctors could not immediately diagnose.

“Finally, I was diagnosed with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is found among the Portuguese, Africans and Appalachian whites,” Kennedy said. “Doctors here thought of sarcoidosis as an African disease, but in fact those black African Americans got the gene for the condition through Mediterranean ancestors.”

Kennedy turned his curiosity to research and began to find evidence that challenged tradition. For one thing, he found that many dark-skinned Appalachians described themselves as being “Portyghee.”

Because many Appalachians can be traced back to immigrants whose ships listed them as Irish, Scottish and English in the early 1700s, Kennedy faces an uphill battle in explaining how Mediterraneans ended up in the mix.

Are You a Melungeon?

The following last names are common among Melungeons. Melungeons say they may indicate Melungeon ancestry.

Adams, Adkins, Allen, Allmond, Ashworth, Barker, Barnes, Bass, Beckler, Bedgood, Bell, Bennett, Berry, Beverly, Biggs, Bolen,Bowlen, Bowlin Bolling,Bowling, Boone, Bowman, Badby, Branham, Braveboy, Briger,Bridger, Brogan, Brooks, Brown, Bunch, Butler, Butters, Bullion, Burton, Buxton, Byrd, Campbell, Carrico, Carter, Casteel, Caudill, Chapman, Chavis, Clark, Cloud, Coal, Cole,Coles, Coffey, Coleman, Colley, Collier,Colyer, Collins, Collinsworth, Cook(e), Cooper, Corman, Counts, Cox,Coxe, Criel, Croston, Crow, Cumba,Cumbo, Cumbow, Curry, Custalow, Dalton, Dare, Davis, Denham, Dennis, Dial, Dorton, Doyle, Driggers, Dye, Dyess, Ely, Epps, Evans, Fields, Freeman, French, Gann, Garland, Gibbs, Gibson,Gipson, Goins,Goings, Gorvens, Gowan, Gowen, Graham, Green(e), Gwinn, Hall, Hammon, Harmon, Harris, Harvie, Harvey, Hawkes, Hendricks,Hendrix, Hill, Hillman, Hogge, Holmes, Hopkins, Howe, Hyatt, Jackson, James, Johnson, Jones, Keith, Kennedy, Kiser, Langston, Lasie Lawson, Locklear, Lopes, Lowry, Lucas, Maddox, Maggard, Major, Male,Mayle, Maloney, Marsh, Martin, Miles, Minard, Miner,Minor, Mizer, Moore, Morley, Mullins, Marsh, Nash ,Nelson, Newman, Niccans, Nichols, Noel, Norris, Orr, Osborn,Osborne, Oxendine, Page, Paine, Patterson, Perkins, Perry, Phelps, Phipps, Prinder, Polly, Powell, Powers, Pritchard, Pruitt, Ramey, Rasnick, Reaves, Reeves, Revels, Richardson, Roberson, Robertson, Robinson, Russell, Sammons, Sampson, Sawyer, Scott, Sexton, Shavis, Shephard,Shepherd, Short,Shortt, Sizemore, Smiling, Smith, Stallard, Stanley, Steel, Stevens, Stewart, Strother, Sweatt,Swett, Swindall, Tally, Taylor, Thompson, Tolliver, Tuppance, Turner, Vanover, Vicars,Viccars, Vickers, Ware, Watts, Weaver, White, Whited, Wilkins, Williams, Williamson, Willis, Wisby, Wise, Wood, Wright, Wyatt, Wynn.

The Missing Link

How could Spanish or Portuguese people have made it into the Appalachian mountains?

Archaeologist Chester De Pratter has some clues. One starts with a 1566 Spanish settlement on Paris Island, south of Beaufort, South Carolina. Under the leadership of Juan Pardo, explorers tried to open up an overland road to Mexico to transport silver. Pardo’s men made it as far as what is now Asheville, North Carolina, and established a small outpost. The following year another group returned, and went near Knoxville, Tennessee.

What became of this group is unknown. They might have been overrun by Indians, or they might survived and lived with the Indians.

DePratter can’t make a direct link to the Melungeons. But the presence of 16th Century Spanish coins in the mountains is tempting evidence that some of the Spaniards lived in the region and survived.

There’s also Sir Frances Drake, who in 1586 attacked an area near Santa Domingo and captured slaves held by the Spanish, including Turks and Moors as well as American Indians. These slaves were being taken to Virginia when a storm came and sunk several of the vessels. Some could have survived and gradually moved inland.

Other theories involve possible members of a party with Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, who were separated during an exploration of the Mississippi and were traveling east when they finally settled in the Appalachians.

While no one has made a direct link to any of these possible lost Portuguese, it is certain that the British, on first viewing Appalachians, did not visualize them as a preserved version of their ancient Anglo-Saxon forbearers. When world-renowned British historian Arnold Toynbee visited Appalachia, he detailed the following observation of its people:

“[T]he Appalachian ‘Mountain People’ at this day are no better than barbarians. They are the American counterparts of the latter-day White barbarians of the Old World: . . . the Kurds and the Pathans and the Hairy Ainu . . . [But t]hrough one of several alternative processes — extermination or subjection or assimilation — these last lingering survivals will assuredly disappear within the next few generations.”

In the 1960s, Whitesburg lawyer Harry Caudill brought this perspective up to date in his classic book Night Comes to the Cumberlands, which attributed Appalachia’s poverty to its people’s ancestry, which he described as the descendants of street orphans, debtors and criminals from the slums of England. Caudill later moderated his views, but the power of his writing and his position as a native Appalachian affirmed widely held prejudices that Appalachians were defective people of a defective ancestry.

As it turns out, Caudill itself is now considered a Melungeon surname, and in a fascinating footnote Caudill said that the surname is of Spanish extraction. Through intermarriage with Scottish- Irish, a strain of “black Scottish” emerged, which Caudill described as “. . . people with swarthy complexions, heavy black beards and coal-black eyes, who contrast sharply with the brown hair and eyes and ruddy skins of the Scots generally.”

Race Colors the Debate

The Melungeon debate is more than a genealogical mystery. It has also revealed how the issue of race strikes a raw nerve in Appalachia.

Throughout time, many states have taken a hard line against mixed-race Melungeons. For example, in Virginia, W. A. Pleckers — who ran the state Registrar of Vital Statistics— wrote in 1925 that “the mongrel groups of Virginia” were the lowest form of humanity — even lower than what he described as “the true Negro.”

Such attitudes affected all of society, right down to who owned Appalachian land. Darlene Wilson, a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Kentucky, made an interesting discovery when studying the papers of 19th century businessman John Fox Jr.

Fox and his brother James were in the business of acquiring mineral rights in Appalachia and had apparently encountered some difficulty in persuading some landowners to sell. Fox acquired the list of Melungeon surnames.

“John told him if anybody he encountered had these last names, idly comment that Tunny, you don’t look white to me,’” Wilson says.

The threat of being exposed as of mixed-race ancestry was enough to convince some in the mountains to sell their mineral rights — and surface rights, if they were really scared. “Which would explain,” Wilson says, “why people in the mountains sold their mineral rights for fifty cents an acre when the same land in Pennsylvania was going for much more.”

Others, such as Fields and Kennedy, found evidence in census records of people designated as “free persons of color” in Virginia who appeared in a later Kentucky or Tennessee census as white. The free persons of color designation branded dark-skinned people — whether American Indian, African American or Mediterranean — as living with compromised rights to own land, marry and move about. When Kentucky and Tennessee formed the frontier, a new courthouse in a new county meant a new chance to gain the privilege of whiteness.

“The courthouse was where you got white, and you stayed white,” Wilson said.

Today in Appalachia, there are people like Connie Clark of Big Stone Gap, Virginia, who has always wondered about the strange silences and gaps when she inquired about her family history. “When I was young and would ask questions about where we came from, they always changed the stories, and that kept me wondering, do they know something they’re just not telling me?” Clark says.

After hearing Kennedy speak, Clark started her own research, and finally her mother admitted their Melungeon heritage.

Clark is now a proud Melungeon and answers phone calls from displaced Appalachians all over the country admitting that their family harbored secrets about their background.

Academic Controversy vs. Creating Community

Some historians have scorched Kennedy’s book and attacked the idea that Melungeons are a unique American people.

Virginia DeMarce, a historian with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, recently traced several Melungeon families back to free blacks and argued vigorously in the National Genealogical Society Quarterly that meticulous research confirms the Scottish-Irish, African and Native American connection.

Even more scathing are the words of David Henige. In this spring’s edition of Appalachian Journal, Henige blistered Kennedy’s book, vivisectioning his arguments about linguistic similarities, his paucity of hard data such as census records and reliance on physical characteristics.

“In all this, Kennedy seems to have been taken in by Turkish historians just as Alex Haley fell victim to his African informants and Margaret Mead to young ‘virgins’ in Samoa. Exhibiting too palpable an enthusiasm to believe what one is being told is certainly no way to elicit objective data, nor for that matter to process it,” Henige wrote.

When interviewed, Henige is at a loss to explain Kennedy’s second printing and the wildly successful reunion in Wise. “Brent Kennedy is an awful historian,” Henige says. “I think people want to feel oppressed.”

Perhaps the Haley analogy is revealing. Haley, like Kennedy, captured the need of disenfranchised people — whose true past had been obfuscated by bigotry — to recreate a history they can be proud of. As coal companies retreat, and back-to-the-landers recede back-to-the-suburbs, Appalachians are left with themselves and are struggling to define what they are that can give them the pride that Roots gave African Americans.

The Melungeon “movement” reunites Appalachians by giving them something to be proud of.

As Wilson says, “For years, Appalachians were seen as a problem. But they were the first peaceful melding of cultures in this country.”

Tags

Judy Jones

Judy Jones writes for the Lexington, Kentucky, Herald-Leader. (1998)