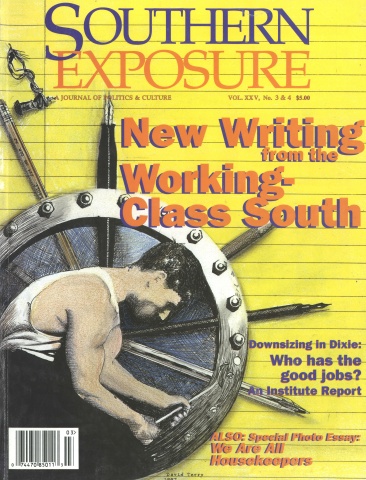

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Denise Giardina has earned her reputation as one of the most honest and moving writers about the southern working class. Ten years ago, her novel Storming Heaven — which traces the lives of four people in a West Virginia coal town, up to a final drama between the community and the bosses — was quickly recognized as a classic portrait of life and struggle in the mines.

Now she has finished her latest novel Saints and Villains (due out from W.W. Norton this February). Unlike Storming Heaven and Unquiet Earth [see review, Fall 93, p. 61] — both set in the familiar hills of her native West Virginia — Saints takes place in Nazi Germany and is a gripping historical narrative about resistance to evil and heroism underground. Yet Giardina still brings it all home, weaving in an appearance by mountain organizing legend Myles Horton, and events such as the West Virginia Hawks Tunnel disaster — an early 20th-century industrial accident that took the lives of dozens of African American workers.

When I called to talk to her, Denise had just gotten a Border Collie puppy who was busy chewing on the cord to her computer, so she had to take frequent breaks.

Storming Heaven and Unquiet Earth focus on about 100 years of history in one small community. What is it about locality that really catches your imagination?

I grew up in southern West Virginia. I think the landscape and its history is really haunting and the ruggedness makes it such a hard place to live.

A lot of writers focus on exotic places. Do you think it’s important to write about the places you know intimately?

I think that’s important. Even when I write about other places, it’s really informed by where I come from. My first novel was set in Medieval England, but the ruggedness about southern West Virginia helped me capture the ruggedness of Medieval England and Wales. I think when you grow up in southern West Virginia, you don’t grow up protected from life. I think that helps when writing about a place like Nazi Germany.

What kinds of experiences in your life do you think are elemental to understanding and writing about basic issues of humanity?

My family was pretty middle class for the area because my dad was the book keeper for the coal company; he wasn’t a miner. We were more privileged than most of our neighbors, but we also lived right among our neighbors. I lived in a coal camp of about 10 houses. There was only one other family that was middle class, everybody else were coal miners. This was a time when the mines weren’t working steadily, so people only had one or two days of work a week.

Our houses were right close together so you couldn’t avoid seeing what people were going through. The other kids next door didn’t have enough to eat and their clothes were just kind of patched together. Their father was killed in the mines just a few years after we moved away. Even my uncle and cousins were struggling the same way. I saw that and it was also a time when people were losing jobs and moving away. Eventually, we had to pack up and move when I was 13.

You got a really keen sense of the power relations in a company town from that age?

Yeah. Even as a child I pretty much knew that nobody had any power over anything. One thing about the coal companies is unlike a lot of industries that use media, they never tried to hide that they were running things. It was like an iron fist.

I wondered if your father being a book-keeper gave you more of an insight into how the coal industry really works because he was management. Or was everything just out in the open?

It was pretty much out in the open. I do think, from his point of view, I heard the company position. He was always trying to do his job. And I would say, “Don’t you feel bad doing this? And he would say, “Yeah, but what can I do about it?” He later had a job — I don’t know what you would call it, but when miners got hurt, the company had people who would present their case and try to keep them from getting worker’s compensation. We disagreed over that.

He would say, “Well, we won a case.”

“Well, did the guy deserve compensation?”

He’d say, “Yeah, but it’s the company’s money.”

One of incidents in Storming Heaven that stands out is where the U.S. Air Force is testing its new technology and bombs a coal camp to put down a strike. I’d heard that story from someone who was a VISTA volunteer in eastern Kentucky in the 1960s. So I wondered if that book was based on real events.

Yeah, that actually happened. The Army didn’t actually drop any bombs. They flew out of Charleston and got lost in fog. They didn’t have navigational equipment and one of the planes crashed. They went back.

The coal operators had also been making bombs. I’ve seen the building in Logan where they actually made them. They just went up in some private planes and dropped their bombs. That’s who actually did the bombing, but certainly the Army Air Force was going to if they could have.

General Billy Mitchell, who is considered to be the founder of the Air Force — he was really into it. There had been some aerial bombardment in World War I from dirigibles. So they wanted to know how to do it with airplanes, too.

There’s a lot of history about communist and radical organizing in the mountains. In what ways do you think the historical record of Appalachia has been distorted over time?

I think it’s terribly distorted. I think most people’s perception of Appalachia is isolated, backward people totally cut off from civilization, and nothing could be further from the truth. Sure, there are a lot of places that are hard to get to, but the area’s always been connected with the rest of the country and with world events. The coal fields, at that time, were right at the center of things. Certainly trains were just as good as anywhere else.

People were connected with what was going on. A lot of miners were socialists. There was a socialist newspaper in Huntington, West Virginia, for example, that had a circulation of thousands just in the Kanawha County coal fields. People voted for Eugene Debs.

I also wanted to ask you about the diversity of the area, from your perspective growing up.

The county where I grew up was just as ethnically diverse as New York City. This woman did a history of the county, which isn’t so much a history as much as a biography of everybody she knew growing up in the county. You literally can find any ethnic group, from Chinese to Syrian to Hungarian to Russian to African American to Polish to Italians. There were lots of Italians. You know, I’m half Sicilian.

There were Orthodox churches. There was a synagogue in Welch.

I grew up in a little coal camp called Black Wolf that was very small, but when you went up a holler there was just one coal camp after another. Our coal camp was very small, but we were just two miles from the next.

So the county was pretty dense at that time?

At that time there were around 130,000 people in the county. Now there were 35,000. They used to have theaters in every town and Duke Ellington used to go play in Welch. It’s like a ghost town now.

Has that area of southern West Virginia lost a lot of its diversity because of the coal not being as plentiful?

I think so. Although there’s still a larger African-American presence there than a lot of parts of West Virginia, it’s definitely not as large as it used to be. When miners were laid off, they laid off black miners first. A lot of Italians were only first or second generation when things fell apart so they tended to leave and go to big cities. I think most of the Jewish families probably left.

The two books I’ve read are concerned with the relationship between corporate power and ordinary community people. Do you think of that as a real basic struggle of human existence?

I think it’s not just in West Virginia that it’s the case. I think everywhere. The economic power has become so global that there aren’t many communities anymore that have a locally based economy, in terms of who controls it. When I was writing Unquiet Earth, I felt like I was writing something that was about what’s happened to the United States rather than what’s happened to West Virginia.

The corporate mentality has no regard for local cultures. . . . People talk about family values and the loss of the family. I think one of the biggest contributors to that is the way the economy forces people away from their homes when they don’t want to go.

I was talking to a housekeeper at Antioch College (in Yellow Springs, Ohio) about how low morale is and how young people my age have really low morale and not a lot of hope. I was wondering if you see that in the labor struggle in West Virginia?

In some ways things are getting worse in terms of people not having outlets or options. You don’t have a strong labor movement now for various reasons although it seems like it’s making a little bit of a rebound.

What do you think is going on in the larger sense that causes that?

It’s a disconnection of control over peoples’ own lives. I don’t think it’s just a working class issue, but also a middle class issue. With anybody who works for somebody else, there’s a sense of not being able to control your life. You might get downsized or you might lose your job. Or you’re working hours where you don’t have any choice whether you work over-time. The economy’s supposed to be booming and jobs are getting better, but they tend to be lower-level jobs.

A lot of your work is about relationships between men and women where a conventional marriage really isn’t possible. Is this something that results from the interference of corporate power in our lives?

No, I think that’s just something I’m personally interested in. I find relationships that you really have to work for and struggle to make right more interesting.

My mom read Storming Heaven to her adult education class and she said they really liked the steamy parts although they related to the politics of it too.

In high schools in West Virginia, Storming Heaven is a popular book with students, although I’m waiting for somebody to object over the sex. I’m surprised it hasn’t happened.

I have to tell you that I actually quit going to church after I read Storming Heaven . . .

Oh no!

. . . because I noticed the contrast between two characters. One was a preacher who became a labor preacher — because those were the circumstances — and the other guy in the story was an organizer. I felt the organizer was more direct in going about the work and the preacher was just kind of catching up. My experience was that the church I was in was grappling with human suffering and hurt in a way that was so symbolic that there was no under-pinning of reality. I wondered if that reflected some of your instincts.

I actually quit going to church while I was writing that book — and when I wrote Unquiet Earth, too. I wondered if I was going to drop out of the church while I was writing this new book, but it didn’t happen. It’s really important to me now because it’s such a strong source of community. Maybe that’s just because I’m 45. I think you go through different phases in your spirituality. Right now, I really like to have that community, but I haven’t always.

But I think the organizer was really spiritual in that he had a call. You don’t have to go to church to be a spiritual person.

What is the importance of the Church to organizing for social justice?

Well, I think spirituality can temper people and remind them of their humanity. A lot of social justice movements can get extreme. Even though they have a just cause, they become violent and cause suffering to others. The church tends to make you think about how you can make things better for yourself rather than pushing you towards taking away from others. I think that’s true of the civil rights movement in the South.

In the mountains, in real rural areas, the church could be a liberated zone where people could organize.

And the church can really give you courage to engage in social change and sustain you through hard times. During the Pittston strike in Virginia, I went with a group of Episcopal clergy and got arrested on the picket line. At a certain point during the strike, there were mass arrests and they were running out of local people to get arrested, so people would come in from outside the community to help out. So here came all these Episcopal clergy with their robes on getting arrested. It gave the miners the feeling that they might be going up against the multinational corporation, but at least they had God. I remember the miners going up to the security people, and joking like, “Don’t mess with God.”

Mountain people have dealt with exploitation and environmental devastation for the past hundred years. What do you think it is that keeps them so strongly rooted against the devastation of the coal industry?

Mountain people have a really strong sense of family and a connection to the land, although that is less strong these days. I think the experience of going outside of the region and being made to feel uncomfortable reinforces that this is a place to come home to. It’s just really comfortable — people take you for what you are. It doesn’t matter what kind of clothes you wear or what kind of car you drive. People are more accepting of eccentricity here.

Tags

Denise Giardina

Denise Giardina, the author of Storming Heaven, lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. (1991)