Writing from the Bottom Up: A Southern Tradition

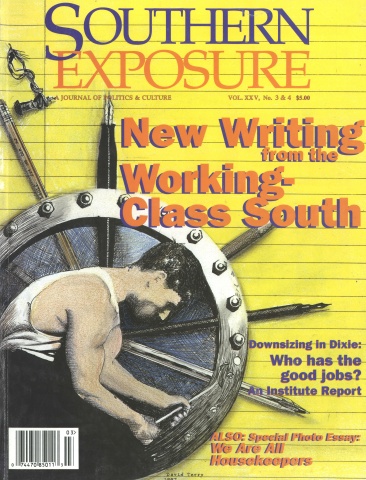

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Among the most indelible images of the South are images of labor: from slaves to sharecroppers, coal miners to chain gangs, housekeepers to migrant farmworkers. And as long as Southerners have worked, they have written about it, creating a body of literature by and for those who work, but don’t own: a working-class literature of the South.

In the following pages, we’ve brought together some of the best new contributions to this proud history. There are short stories and poems, as well as testimony from working-class writers about why they write — how the act of putting a pen to paper fights isolation and helps them beat the odds.

While putting together this issue, we’ve been asked — and have had to ponder ourselves — the question: what makes a story “working class?” A precise definition may be impossible. But looking back through our region’s history, the South has a tradition of writing that is unmistakable.

Southern working-class writing springs from the rich, murky soil of this land with lyric intonations of real people’s speech, a strong class consciousness, and a hardnosed realism born through the experience of class and racial injustice. Sometimes it’s fiction, often not; sometimes it’s been written by those who are working class, often not. But at its best, it has always been writing that has started and ended with the struggle of ordinary folks not only to survive, but to understand and transcend the circumstances of their lives.

Some writers have focused more on survival, some on transcendence; the difference has often been closely related to the political and economic climate of the day. During the ’30s, for example, radical movements inspired “proletarian novelists” to describe the glamour of struggle and the possibility for social change.

In today’s corporate era of downsized workers and expendable communities — and popular opposition with its back against the wall — hard times are reflected in writing that often dwells on the personal struggle to persist.

But these stories published here stand within the South’s unbroken history of writing from the bottom-up, the southern working-class tradition, which began some 200 years ago.

The Color Line

Of course, working-class writing in the South has always been about race as much as it’s been about class. In fact, the first significant body of southern working-class writing were slave narratives, which included literally thousands of writers, including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs and William Wells Brown.

Work — both in slavery and after freedom — figures importantly in slave narratives. There’s Douglass’ experiences in the Baltimore shipyards, where he was beaten up by white apprentices fearful of the competition of slave labor; and Brown’s work as a slave preparing other slaves for auction: making older slaves seem younger, and more valuable, by shaving their whiskers and using shoe polish to darken their gray hair.

And many slave writers were fully aware of their relationship with the white working class. They often realized that the southern power structure had a strong interest in stoking racial resentments among poor whites to keep them from making common cause with their black counterparts.

But while the energies of resentment could be harnessed to maintain white rule, they made for dangerous, unstable weapons. Jacobs, who escaped slavery by hiding in a cramped attic for almost seven years, writes in her 1861 autobiography that white paranoia seized Edenton, North Carolina, following Nat Turner’s insurrection in 1831. The town raised a militia made up of “low whites, who had no negroes of their own to scourge . . . not reflecting that the power which trampled on the colored people also kept themselves in poverty, ignorance, and moral degradation.” But the angry vigilantes did not only attack slaves and free blacks; their rampages ultimately threatened privileged whites, too — and the posse had to be disbanded.

Perhaps this racial solidarity based on “whiteness” is the reason that whites were slow to join African Americans in understanding the role economic class played in the “race problem.” For example, America’s first well-known industrial novel, Life in the Iron Mills, was written by a Southerner — Rebecca Harding Davis of western Virginia in 1861. With righteous zeal, the novel movingly described the indignities of factory life. But missing was the role of race, or any sense that a new class was being created: the industrial working class.

Southern Writers “Go Left”

It was not until the 20th century that a large body of white class-conscious writers began to appear. As factories and mills began to industrialize the South, writers such as Ellen Glasgow, T.S. Stribling, Lillian Smith, Harry Harrison Kroll, Erskine Caldwell and Paul Green wrote about — in a wide variety of styles and genres — the social, economic and racial injustices of the day.

Some of these writers were working people. Most were not, creating a dilemma that has always confounded southern writers who have taken the working class as their subject. When James Agee and Walker Evans were sent by Fortune magazine in 1936 to document black tenant farmers in rural Alabama — resulting in the classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men — the writer Agee soon became tortured by his relationship to what he was attempting to describe. By the time the book was published, it had become unbearable. Agee repeatedly states his self-disgust at his inability to accurately render “the cruel radiance of what is,” and eventually reveals his scorn for his sponsors, himself and even his readers: “It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying, that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings.”

This tension continued when the 1920s and 1930s saw an explosion of explicitly socialist and communist writers — the “proletarian novelists” — who were influenced by the radical movements gaining currency among workers and intellectuals alike. “Go left, young writers!” was the cry, and it was heard in the South as much as anywhere, myths of southern “anti-communist sentiment” aside.

Southern proletarian writing had two aims. One was to simply open a window to the life of working and poorer classes, such as Nelson Algren’s Somebody in Boots, the tribulations of a down-and-out Texan written in 1935. The second was to highlight the possibilities and tensions of class struggle. One of the country’s most famous proletarian novels was Grace Lumpkin’s To Make My Bread, a heroic portrait of the 1929 textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina, which inspired a series of stories and books.

Race was never absent. One reason, as Alan Wald has pointed out, is that white leftists often used “African-American protagonists to dramatize their views and concerns.” A prime example is Alfred Maund’s The Big Boxcar (1957), in which a group of black drifters and a white man exchange stories of their lives and bond in solidarity. The male and female protagonists leave the train in Birmingham at the novel’s close, destined to become leaders in the civil rights movement.

Race was also central because African-American writers were part of the southern radical writing tradition, which extended into the 1950s. These included famous writers like Richard Wright, but also William Attaway, Arna Bontemps and Sarah Wright, among many others. One of the most prominent post-war novelists in this category is John O. Killens, whose Youngblood (1953) follows a southern black family as they develop both a racial and class consciousness and a spirit of resistance.

New Writing, New Generations

Since the decline of organized worker radicalism after World War II, fewer southern writers have identified as working class writers. But the tradition continued into the 1960s, with the flowering of Appalachian literature, the Cajun renaissance and writing drawn from the African-American and Chicano liberation movements.

As the new generations of writers make clear, working-class literature has never been just about work. Perhaps in the South more than anywhere else, it’s also about community identity, and the ordinary people whose small actions and great courage make up the fabric of culture — which is increasingly under siege. As Richard Walker, co-editor of the anthology Getting By: Stories of Working Lives, says: “This writing is important because we have a whole class — the working class — in danger of losing its culture, and therefore its identity.”

So maybe it’s not surprising that there’s a common theme among the writers in this issue: that the greatest enemy of the working-class writer is isolation. Bringing these writers and their writing together is the first step to rebuilding a sense of culture.

These stories, taken alone, can sustain us through hard times. Taken together, they become a broad expression of beauty and resistance.

Tags

Gary Ashwill

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.