This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

First, let me give you my credentials. I have no degree or Ph.D. I am a mother of five, a stepmother of four, a poet, writer and hair designer.

I write about many things. I write about money because I am bankrupt. I write about birth control because I have five children. I write about marriage because I have been married three times. I write about washing the kitchen floor because that is what I do. I write about feeling like a shitty mother because, sometimes, that’s how I feel. I write about orgasms because I feel they are important, but most of all, I write because I want to listen. I give what I want. I want to hear your stories. When you speak I learn.

It’s not about getting a degree, it’s about being free and pressing through the blinds of oppression of our old high school, the university too, or that big-time job we got we thought was it. I’m talking about prying through to the freedom of our voice—the I am and I want and I will.

They tell us to write, the scholars we find on bookshelves, the outspoken women we hear at lectures and conferences and in our own midst. They tell us to write, the educated, the many degreed, the women with dreamlike jobs, climbing, don’t they know, endless ladders. They tell the uneducated, the nonacademic, the rural women, the poor women, the inner city women, the stay-at-home mom, they tell us to write. So we write. We write at the kitchen table and at the stop lights, between appointments and at the playground and then we read it. We read it to other mothers in the park, children interrupting. We read it in the kitchen when the kids come home from school, the telephone rings and the stage is the kitchen table.

We write and we find our hearts aching to spill it out. We find our souls wanting to scream it. We find our lives rise up out of the pages. We find rhythm and music in our words. We find stories we’ve told and retold and we discover we have desires we never knew we had and we desire to write more.

We desire to be heard and we want to read it and even when we’re too shy to read it, we wish we weren’t and when we’re ready, when we want someone to hear it, no one is listening. ’Cause there’s nowhere to read it. The academic feminist is too busy making speeches and her publisher wants polished pieces written in penta something meter or in proper English and university classes take time and money we don’t have.

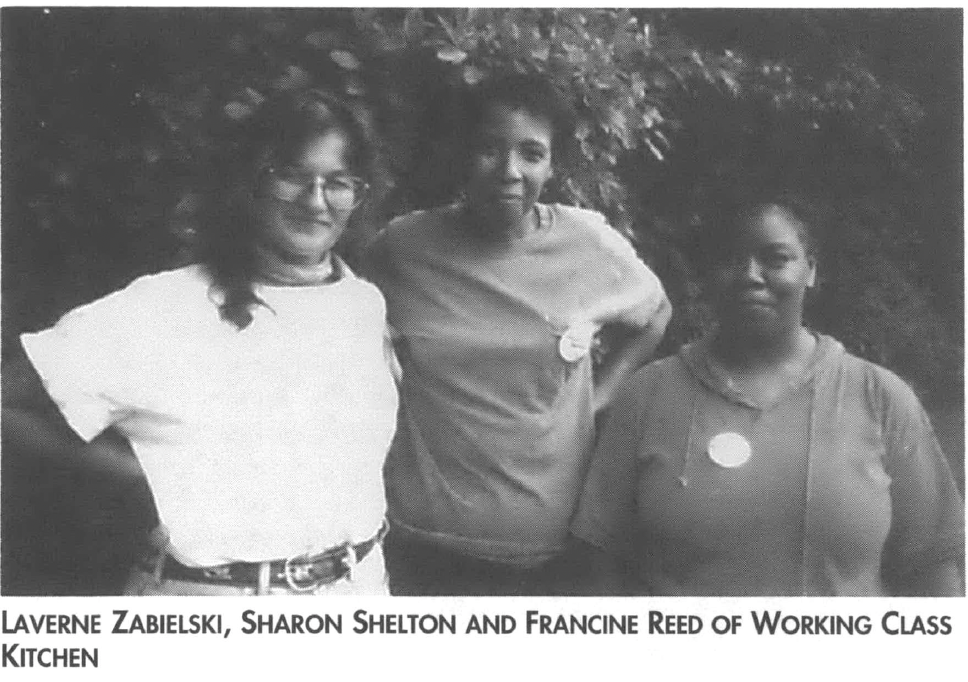

The Working Class Kitchen created another stage, someone’s home, a local restaurant, a community center. We invite six writers from different communities and they invite six friends, we have an audience of 36. The script is left wide open. Read what you want, how you want, wear what you want. And what is read is good, without a jury, without an “A,” without publication because the WCK trusts the process.

At the Working Class Kitchen the world moves to the microphone. The writer’s fear, when she reads her work, sometimes for the first time, gives power to her words. Her strength gives form to her voice. You see her facing her. You see her dancing naked. You hear the sounds of her voice shaking and the vibrations resonate through you and you be still and you listen because you see the birth of life before your very eyes. You see a revolution.

Everyone has the Working Class Kitchen in them somewhere. The heritage we came from is buried deep. If you have to race your paycheck to the bank you’ve got it in there. The struggle to survive is the Working Class Kitchen.

The Working Class Kitchen wants to hear it in your words, in your tone, in your voice. We want to see it written the way you spell it, the way you hear it. We want to break down the walls of illusion of false education keeping us silent, the working class silent, because we don’t write it their way, see it their way, dream it their way, believe it their way. Everyone has a “their way” that they want to break through and the only way out is through your own voice.

It is as George Ella Lyon says in her essay “On the Writer and the Community:” “It’s not waiting for just the cream that rises to the top because there’s a whole lot of cream at the bottom.” So read it at the WORKING CLASS KITCHEN!