This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

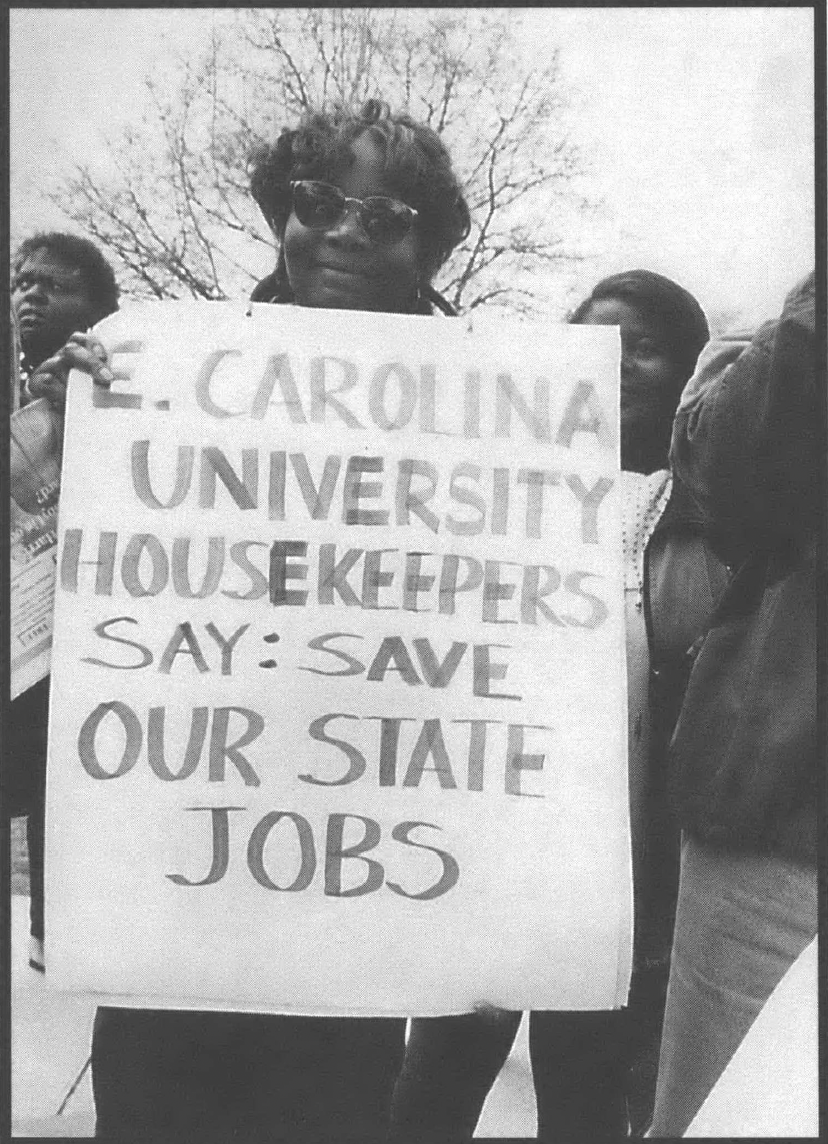

Since 1995, Susan Suchman Simone has been documenting the lives and political action of the UNC Housekeepers Association—an organization of housekeeping staff at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We Are All Housekeepers” is a photo essay based on images selected from The Meeting Place Project, a photographic and oral history project that records the words and lives of African-American workers in Chapel Hill.

As Jeff Jones, a doctoral student in history at UNC, relates in his accompanying historical essay, the conditions and struggle Suchman Simone depicts in the 1990s are deeply reminiscent of the university’s past. For the last 60 years, university housekeepers have faced remarkably similar affronts to dignity and justice. Yet injustice has rarely gone without challenge, and the last 60 years have also been marked by a persistence on the part of the campus’ worst-treated workers to fight for a better life.

Last fall, UNC settled a seven-year-long discrimination suit filed by Marsha Tinnen for the UNC Housekeepers Association. A year later, not one of the stipulations of that agreement—including regular meetings, training and other benefits—has been fulfilled. When housekeepers and supporters rallied against the administration’s inaction on University Day in October 1997, Chancellor Michael Hooker responded, “Obviously there is something left unsettled. I’m not exactly sure what the issue is.”

As a look at the last 60 years of the housekeepers’ struggle indicates, the issue is a history of injustice and racism, reflected in the low pay and poor working conditions of the predominantly African-American and women housekeeping workers. The fight for justice has gone through ebbs and flows, but the basic underlying issues of justice and dignity have remained constant.

The first wave of resistance came with the Janitors’ Association, formed in 1930 on the heels of a 10 percent wage cut for state employees—the lowest paid of whom received only $25 a week for more than 50 hours even before the cut. Organized by four janitors and led initially be Elliot “President George” Washington, the Janitors’ Association met regularly, paid dues, published a newsletter, held a yearly cookout and agitated for more than 10 years.

During the 1930s, UNC Chancellor Frank Porter Graham tells of attending a meeting of the Janitors’ Association, during which he discussed his plan to start a financial aid fund to help students who could not afford to attend the university. The members of the Janitors’ Association at the meeting immediately passed the hat and, despite their meager wages, raised $ 10 as the first donation to the chancellor’s new fund.

During World War II the Janitors’ Association gave way to the Congress of Industrial Organizations, with student representatives of the union organizing campus workers. In the face of rapidly rising wartime living expenses, housekeepers and laundry workers pressed demands for job security, advancement opportunities, improved working conditions, and better pay through elected stewards and union officials.

Students and university employees worked together in the drive, as the 1947 “Higher Math/Lower Math” flier indicates (page 60). The university often sought to undermine their efforts. In 1944, C. I. O. Secretary-Treasurer Henry Wenning sent a letter to Graham, then serving on the National War Labor Board in Washington, D.C., complaining that university administrators were trying to turn the union’s demands for working rules and regulations into contract negotiations, a “hostile act” that, Wenning points out, would allow the university to wipe out the union.

Throughout this period of union organizing, mistreatment of workers by supervisors was a common theme. In 1944, Williams noted housekeepers’ objections to poor treatment by Giles F. Horney complaining that he “refuses to discuss points of disagreement,” “fires men without just cause” and displays an “attitude [that] is uncooperative and generally unfriendly.” A letter written three years later by housekeeper Luther Edwards (page 57) on behalf of Bessie Edwards describes one supervisor, Mr. Sturdivant, as an “evil boss” who “came cursing” about the time sheet instead of “coming in a human way.”

The 1950s brought a lull in campus organizing, but documentation from the period still reveals a great deal about the University’s relationship with its workers. A 1954 memo, for example, announces that the classification of jobs will begin with the lowest-paid positions, admitting that there may be “misunderstandings, suspicions and fears” among those employees. A petition circulated among campus workers several years later explains why there was apprehension, citing “the problem of the inequitable wage scale” in the University’s classifications.

With the Civil Rights Movement came a new round of organizing on campus. In 1965 the newly formed Committee of Janitors wrote university administrators to complain about low pay, poor working conditions, and unfair treatment by supervisors, indicating that the situation had not improved markedly over the years. Echoing the sentiments of campus workers, Sociology professor H. M. Blaylock complained in a letter to Chancellor Paul Sharp that one supervisor, Mr. Olive, believes “that Negroes should be completely subservient.”

The thread of discrimination and struggle did not end with the civil rights movement. In 1980 housekeepers compiled a list of “Grievances and Demands” stemming from an incident in which supervisors “wrote up” or reported housekeepers who did not drive to work during a snow storm. Among the demands are that supervisor Manzie Smith, “well-known to sexually harass women workers,” be removed from his position. Three years later a university administrator noted that “housekeepers were quite vocal about pay (or lack thereof)” in a recent meeting, adding that “there is such strong sentiment that a petition is being circulated among housekeepers.”

A state hiring freeze and budget cuts in the late 1980s sparked the formation of the Housekeepers Association, which has put forward many of the same demands presented by their predecessors. The movement quickly spread to campuses in Greenville and Greensboro. A new challenge has been university plans to privatize, which is often held as a threat against public sector organizing—and the key reason the recent settlement, even if honored, would not end the fight.

Now the struggle has taken a new form. A drive started this June, organized by the independent United Electrical Workers Union (UE), has taken the struggle statewide, organizing housekeepers and groundskeepers at all 16 campuses in the UNC system. Student support has again been crucial, with brigades at each campus talking to workers and collecting grievances.

In many ways, the conditions of UNC housekeepers have stayed very much the same. But just as injustice has been constant, so too has been the dedication of housekeepers to change the course of history.

Letter written to P.L. Burch, Superintendent of the Buildings Dept., by the head of the Janitors’ Association (formed in 1930) following a second 10 percent wage cut and reduction of hours. The letter indicates that, despite the cuts, several janitors continue to work extra hours — for no extra pay — to keep buildings clean.

This summer we are doing every thing in our power to keep the building as it have all waise been, and we relisse their are know money for extry hours work but with the same spirit we do our work that the standard of cleaness may be maintain. To do this several of us will have to come early and stay late.

I am wondering if a letter could not be sent out to the head of the Department to wich these men work and make a check of the personal ability, and at the end of the first Summer School we send a short questionear to them as to the outcome of the house system to that this be keep in confident until the questionear have been return. Your criticism on this is greatly appreciated.

Yours, Kenneth Cheek

This letter, written by Luther Edwards on behalf of Bessie Edwards in April 1947, complains about a style of supervision and describes the plantation mentality that has persisted in the Housekeeping division at the university.

Dear Sir,

Bessie Edwards has worked for the university for many years always trying to please. Recently there has cause of some complaint about the time sheet and the boss came up cursing about how they should be filled out — instead of coming in a human way.

We are glad to serve, but how in the devil would you expect any decent person to give service under such evil boss. I figured you should know this so you could remedy the same.

Thanks

Luther Edwards

The one I am referring to is Mr. Sturdivant.

Tags

Susan Suchman Simone

Susan Simone is a documentary photographer based in Chapel Hill, NC. Her Meeting Place project is a sponsored project of the Institute for Southern Studies. These images will be the elements of a larger exhibition at the Chapel Hill Town Hall August 27-October 1, 1999. (1999)