Temporary Balance

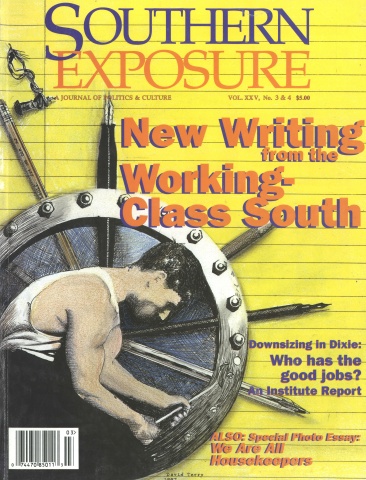

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Fred spied Digger out the corner of his eye. He was coming from the balancers, where he and Chickenman had been whoopin’ and hollerin’ about God only knows what. Maybe Chickenman had told him about getting clotheslined over the weekend. Chickenman was always full of it on Mondays. Fred had only been working at Schwitzer Turbochargers three weeks, but he knew that; and he knew that before the night was out, Digger would be over there three or four more times for 20 to 30 minutes at a stretch.

Fred cracked the door to the Bupi Wash. He watched a thin sheet of steam ooze and climb over the back of the machine towards dangling air hoses and power cords, up through dull yellow lights, curl around one of the beige steel beams in the ceiling and float across the plant. No need to get blasted all at once. Schwitzer was a great place to work because it was air conditioned. In fact they had to keep the temperature here the same year round. “Variations in temperature affect the dimensions of the parts,” Digger had told Fred his first day. “We are working with expensive metals here. The wheels on these shafts are nickel alloyed. The big ones cost about a hundred dollars apiece.” Digger told this to all greenhorns from Manpower Temporaries first thing, and he was careful to lecture them over by the contour grinder where the huge pink grinding wheel and its pale blue safety guards blocked the view of steam spewing out of the Bupi Wash. Fred hadn’t figured out why Digger bothered. No steam from that washer could ever be as rough as scrubbing shirt collars at Biltmore Cleaners or pulling grocery orders at the Ingle’s Warehouse or even washing dishes at the Grove Park Inn. Compared to those, this was a pie job. If Digger thought washing shaft and wheels was bad, he must not know much about the other places Manpower sent you.

Fred pulled the huge H-shaped metal handle down to the concrete floor while billowing clouds of steam blinded him for a second, maybe two, a fine hot mist enveloping his entire upper body. To ensure the handle was securely on the floor, he walked to one side and kicked it out just the way Digger had taught him. The handle now served as a pair of legs and the backside of the door as a tabletop to roll the parts out on. Fred used his utility rag to roll out the large iron rack holding the two orange baskets.

“You need to speed up!” Digger’s voice was shaky. He was forcing a fake smile, fumbling at his plaid shirt pocket for a Winston.

“But I thought you wanted me to do a good job,” Fred said.

“I do. But I want you to be here tomorrow, and the supervisor on first shift is riding my ass about you. If we don’t start getting more parts out of here, they are going to let your butt go. Maybe mine, too.”

Fred took the air hose and started blowing out the milky water that had collected in the centers on each part. He blew off the slick glistening shafts, the piston grooves. The piercing whistle of compressed air made him frown. He had grown immune during the last three weeks to the constant roar of machines throughout the building, but the pitch of compressed air hitting those center holes grated his spine.

“What’d you do this weekend?” Digger had his Winston lit and was puffing smoke right in Fred’s face. He was dark-complected, bald and on the chubby side.

“I went up Mount Mitchell.”

“What’d you go up there for?”

“Cause I hadn’t ever done it before. And it was something to do.”

“Well, did you like it?”

“Not really. The trees up there are dead.”

“Well, try to get more parts over there to final inspection tonight. Randy says we ought to be averaging about 1,500 a night, and we ain’t even coming close to that.”

Digger walked off, worming his frame between the back of the washer and the threader. Fred watched him as he headed for the Tocco Induction Hardener. He wondered what Randy had told Digger to tell the guy over there. Randy, the first shift supervisor, is crazy, and Digger hain’t got the balls to tell him. Fifteen hundred parts a night!

Fred started figuring in his head: 16 parts to a basket and two baskets to a wash with a 10 minute cycle time; that was 192 parts an hour. Multiply that times eight and you got 1,536. Fred was good at math, and he was good at hating people like Randy.

People like Randy sit at a desk in a white shirt and navy polyester pants and figure out how everything should work. They don’t allow for blowing off parts or wiping off parts or deburring parts that get sent back by the quality control inspectors. They don’t remember that parts sent back must be rewashed because the brush used to deburr those piston and compressor OD’s make the shafts dirty again. They don’t think it takes time to load and unload the washer. They have never understood that when a machine goes down it slows production. And breaks for employees never factor into their game plans. All they really care about are numbers. They were born to kiss ass, fill out charts, and step on little people.

That was Fred’s steam-cleaned view of the whole situation, and he felt that his animosity towards the Randys of this world was perfectly justified.

It was the Diggers of the world Fred couldn’t understand. The first week Digger had preached to him about the importance of being careful. “Scrap is the worst thing you can create,” he had said. “You are expected to treat every piece of material and every machine in this plant like you paid for it yourself.”

Fred had taken him seriously. Though the building was full of old grinders and lathes, there were new ones, too — high-powered Okumas, where you punched numbers on a control panel, shut a door, pressed a start button, and listened to a high hum telling you that your work was being done. The plant was clean, and the operators seemed to take pride in their work. There were even signs attached to each machine reminding employees of its value: I represent a $34,000 investment in your company’s future. Please take good care of me, or I cost $56,000. Please keep me clean and serviced.

Some people were cynical as hell about that, but Fred loved it. And he loved the smell of green coolant in the machines and the voices of the actual workers. He wanted to stay, so he would have to do better. More parts. He’d have to concentrate on getting more parts.

Halfway through dinner break, Fred entered the cafeteria and found a young Chinese girl already taking serving spoons out of the mashed potatoes and string beans. She slipped them back and eased behind the cash register while he grabbed an orange tray and filled a styrofoam cup with sweetened iced tea. She might work out if the rednecks didn’t scare her off. Fred already liked her better than the grumpy old fat woman, who was so concerned with portions that she charged Chickenman double for his French fries last week. Who the hell did she think she was feeding? Sparrows? Working men have to eat. Chickenman wouldn’t ever buy another tater from her — fried or mashed.

Fred loaded a paper plate with meatloaf and large helpings of the two side dishes. By the time he got a dinner roll out of its plastic bag, the Chinese girl was calling out his total. He handed her a five, crammed the dime and penny she gave back into his pocket, and shoved off. He stopped at the round island in the middle of the floor for ketchup packets, plastic utensils, and paper napkins. Everything in here was too bright after four hours on the plant floor. There were white walls and white tables, and you walked on glossy tile. Fred wondered how much the company paid to keep such a slick shine on the tile. He wondered if a temporary did the work.

Fred breathed easy and long, pushing tense air from his stomach and chest. He walked over and sat at a table with Chickenman and Milky Way. Chickenman had a blue-and-white Igloo cooler by his chair and held a sloppy joe that his mama had packed for him. He also had a 20-ounce bottle of Mountain Dew from one of the machines. The new cashier would have to prove herself.

“Where ya been, Wilson?” Chickenman’s mouth was round and small; his voice, like a bass drum.

“I needed to get two extra baskets of parts in the wash,” Fred said.

Chickenman’s face revealed nothing. He was red curly hair from cheekbones to belly, and his cobalt blue eyes stayed solid as marbles, deep in their sockets. If Digger had told him about riding Fred’s ass for more parts, Fred wouldn’t know until Chickenman wanted him to.

“You’re burning it up ain’t cha. You must be wantin’ ’dem boys upstairs to hire ya. Have they said anything about hiring ya yet?” Chickenman took a swig from his Mountain Dew and grabbed another sloppy joe out of his cooler.

“How many of them damn sloppy joes you got?” Milky Way said.

“Five. This is the last one.” A half circle of soda dampened Chickenman’s mustache.

“Well, what else you got in there?” Milky Way was finishing up a microwaved bowl of spaghetti. Bringing food from home was popular if you had a wife or a mama, but Fred didn’t have either.

“Oh, I got a little chocolate banana pudding,” Chickenman said. “So what about it, Wilson? They said anything about hiring ya?”

“Nope.” Fred squeezed packets of ketchup over his meatloaf.

“Well, you ought to go in that office and tell ’em to hire ya or fire ya.”

“You think so, huh.”

“Well, hell yeh! They ought to hire any man that’ll work through breaks like you do. Tell ’em you’ll go to school. Tell ’em you plan to stay here the rest of your workin’ life. Tell ’em any damn thing.”

Milky Way, chewing his last mouthful of spaghetti, reached back to his hip pocket and pulled out an Asheville Citizen-Times. “Sure, Chickenman. That’s great advice. And if all else fails, Wilson can just step behind Randy’s desk and offer to give him a blow job.” Fred closed his eyes and shook his head while they laughed.

“You’d better not go raising cain in those offices, man.” Milky Way fingered the visor of his red cap. “They don’t keep many temporaries around here.” He began to study the sports page.

“Well, you might want to ask Digger,” Chickenman said. “He could put in a good word for ya.”

“Damn!” Milky Way said. “The Braves lost again. That’s the third time this week.”

Fred swallowed hard, forked off more ketchup-smothered meatloaf. Milky Way’s drooped head left the stitching on his cap eye level with Fred. Schwitzer in fat white letters. All permanent employees got one the day they were hired.

“Baseball sucks!” Chickenman said. He was digging into a Cool Whip bowl full of chocolate banana pudding. “I’ll be glad when the NBA season starts.”

“Wilson, tell this fat motherfucker baseball don’t suck.” Milky Way never looked up from his paper.

“Baseball don’t suck.” Fred shovelled in the mashed potatoes and green beans as fast as he could. Time was short. He could already hear metal chairs behind him, sliding against that slick tile.

“Wilson don’t like baseball either. He’s a tennis man. Ain’t that right, Wilson?” Chickenman cupped one hand in his lap while using the other to rake fingers through his beard. Bread and vanilla wafer crumbs fell.

“Oh yeh?” Milky Way’s wrinkled face rose from under the brim of his cap, lifting Schwitzer out of sight. The newspaper was folded and lying on the empty spaghetti bowl. “Randy likes tennis. He belongs to the Asheville Racket Club. Can’t you just see that son of a bitch over there in his white shorts running down tennis balls?”

“I can’t imagine belonging to a club,” Fred said.

“Why, sure you can!” Chickenman said. “If Manpower rolled out enough dough, you’d be out there in your white shorts in a heartbeat.”

“I mainly like to watch.”

“You hear that, Milky Way. He likes to watch.” Chickenman stretched his eyes like those words might be the last.

Fred stacked his trash. “Well, the thing I need to watch right now is the Bupi Wash — a $27,500 investment in your company’s future.” He walked away from the table, but from the garbage can he could still hear Chickenman call, “You are full of shit, Wilson: pure fuckin’ shit.”

Fred pushed a buggy of parts to final inspection. According to the clock there, less than an hour had passed since dinner break, and he was already fighting a case of drag butt. He stared at the bright yellow steps by the far wall that led to engineering and management offices on the second floor. The lights up there were turned out. Fred had seen those workers leave at five o’clock every afternoon, strutting down the catwalk like they owned half the Great Smokies. They were in a rush to get to new cars and big, fine houses. He’d also seen them looking down on the hands that built their blueprints and carried out their game plans. But now all he saw was dark glass.

“Where you at?” Milky Way stood with his elbow propped on a basket beside Fred.

“What?”

“Where you at?” Milky Way rubbed the side of his nose with his thumb. “My machine’s down, and they ain’t got nobody here from maintenance to fix it, so Digger told me to come over here and help you.”

“Oh!” Fred motioned him over to the Bupi Wash. “We’ve got two buggies that were sent back from day shift. They’ve got burrs on the piston OD’s. You can work on those at the brush if you want, and I’ll keep washing.” Milky Way nodded.

They worked together for a couple of hours without saying anything. Milky Way deburred about two parts before deciding to get a stool to sit on. He must have walked all over the plant looking but finally came back with one in tow. There had been several nights when Fred had stood at that brush for ten hours deburring parts, and here was a permanent employee who wouldn’t stand there for ten minutes. Fred didn’t know whether to be mad at Milky Way for finding a stool or at himself for never thinking to ask for one. Milky Way got parts out once he came back, though. Fred envied his speed, and told him so.

“Well, I’ve always been fast,” Milky Way said. Then, he began talking about his high school baseball career. Some small colleges were interested, but his girlfriend got pregnant near the end of his senior year. “We got married and have stayed together.” Milky Way said. “You show me half of ’em that would do that today.”

Fred imagined a young Milky Way’s stern round face staring down batters from a pitcher’s mound. The man had wrinkled prematurely, but he was fitter than most machine operators in the plant — big arms, barreled chest. No beer gut. He said that he could still throw a decent fast ball, and Fred believed him.

“Did you play baseball in high school?”

“Basketball.” Fred wiped shafts as fast as he could.

“But you didn’t play around here, did you? “

“No.” Fred didn’t play much in Johnston County either. He rode the bench mostly, but that was a six hour drive and four and a half years ago. Nobody here knew what kind of player he’d been there.

Milky Way grabbed a can of Skoal from his hip pocket and pulled the lid off. “Chickenman says you’re in these mountains all by yourself. That all your people live in the flatlands.”

“That’s right.” Fred wiped the last shaft in that basket and stopped.

“Why come?” When he saw Fred shrug, Milky Way lowered his head and stuffed a thick pinch of tobacco in his back jaw. Then, he straightened up and waited for an answer.

“I came skiing with friends when I was a junior in high school and decided that I wanted to live here. So the week after graduation, I moved to Asheville.” The ski part was a lie, and Fred didn’t know what made him tell it. The trip had actually been summer church camp.

“Have some?” Milky Way held out the open can of Skoal to Fred.

“No, thanks.”

Fred glanced over at Chickenman, taking metal off the backface of a part. A fine silvery mist sprayed specks of metallic dust into Chickenman’s beard and onto his mint green goggles.

“I’ll be in the john reading if anybody wants to know.” Milky Way had gotten a Field and Stream out of his tool box and was walking towards the restroom. Fred pushed another buggy of parts to final inspection. He’d be alone for the next half hour. Following Randy’s game plan, that was enough time to wash 96 parts.

The thought of getting too tight with Chickenman or Milky Way gnawed at Fred. He’d lost a job at Biltmore Cleaners by hanging out with a guy who was caught stealing money from the coin-operated washers and dryers. Fred didn’t steal any money; but since he’d been seen shooting pool with that guy, and the two had taken some chicks to a few beer joints together, the manager canned him. Manpower sent him to Schwitzer with instructions to stay away from persons of questionable character. Fred took that to mean everybody.

Chickenman wouldn’t let Fred just do his job and get the hell out, though. He started spitting out questions through all that facial hair on Fred’s first night, pecking for information like a television talk show host, and mixing it in with stories about himself and everybody else in the plant. He was nosy as hell and persistent, but good-natured. By the end of Fred’s first week they were car pooling.

Chickenman drove a ’78 camouflaged Blazer and listened to Hank Williams, Jr. Everyday before work, he stopped at the Hot Spot and bought two Goldrush ice cream bars. “I could eat ’dem son bitches till my dick fell off,” he’d say. He talked about riding his Panhead to Harley rallies at Daytona and Myrtle Beach, and he thought Magic Johnson was a bigger legend than Michael Jordan. He claimed to despise two things: any implication that somebody was better than him, and any negative comment about his mama.

Last Saturday, Fred played basketball for the first time since he’d moved to Asheville. Chickenman took him to the old Biltmore School gym, where a girl in gray sweat pants and a Grateful Dead T-shirt collected two bucks apiece from each player. She worked for the county rec department. The money wouldn’t pay her salary but did help cover the light bill according to Chickenman. Eight people showed up, so they decided to run four on four — full court.

Chickenman could move despite his big gut. He blocked out. Pulled rebounds. Cleared lanes. Drove the length of the floor. He was pickin’ and rollin’, shakin’ and bakin’ in purple paisley shorts that revealed ugly spindly legs.

Fred played soft until Chickenman called him aside after the first game. “Listen,” he said. “You’ve got to start leaning on some people, or we’re gonna trade your fuckin’ ass to the Clippers or somebody. A big boy like you?’ A giant drop of sweat dripped from his beard to the floor. “Don’t play scared.”

Fred became more aggressive with each game, thanks to continuous prodding by Chickenman; but the only way he could stop most players from driving was to reach in. Fred called so many fouls on himself that Chickenman swore he must be a Sunday School teacher. Finally, in the last game, they were on opposing sides when Chickenman intercepted a pass with Fred, the only player between him and the basket. Fred wasn’t squared up, and his feet felt like lead; but he had been burned too many times to let Chickenman have an easy lay-up. He stuck out his arm and caught Chickenman right under the chin. The big guy’s knees buckled, and he seemed to fall to the hardwood in slow motion. From midway the paint to the top of the key, Chickenman’s body was stretched out like a corpse. Fred stood over the purple and red heap, holding his breath at the hush he’d caused.

“Gosh dang!” Chickenman’s eyes shot into Fred like two sapphire lasers boring a hole through his windpipe. “I said lean on some people, Wilson, not clothesline my ass.” He was laughing. And suddenly they were all laughing, except Fred, who just sucked in air.

“How many you got?” Digger made him jump. Fred hated when people came up from behind.

“I don’t know exactly.” He looked at the clock over at final inspection. “Somewhere around 700, but 96 in the last 35 minutes.”

Digger lifted a part, twirled it in his nicotine stained fingers. “Well, that’s pretty good. If you can get 1,200, I might be able to keep you.” He walked off without asking about Milky Way, who Fred noticed was at the other end of the aisle, easing their way.

Outside, Fred leaned against Chickenman’s Blazer and watched taillights zip around the curve at the crest of the service road. Red lights zoomed in and out of sight like flickering cautions. He listened to the rhythms of vehicles accelerate on the main road and engines rev in the parking lot. Compared to the noise in the plant, the traffic sounds were small and easily absorbed into the cool night air; but according to the paper, residents had complained.

Chickenman pushed Fred’s passenger door open from the inside, and while Fred was climbing in, Chickenman dropped his cooler on the seat between them and cranked up. The Blazer was the loudest and roughest sounding vehicle on the Schwitzer lot. Fred liked the way air seeped in around the windows and through cracks in the rusty floorboard. The faster they rode, the better the ventilation. He closed his eyes and rested his head against the back glass.

He could see parts — full buggies of shaft and wheels floating in the French Broad River. He’d see them in his sleep tonight. He’d seen miles of ring around the collar in his sleep before, and huge brown boxes of groceries stacked as high and the heavens. Once, he dreamed that there was an international dishwasher strike, and all of the fine china in the world was dirty. Rich people at the Grove Park Inn were eating out of paper plates. And weeping.

Chickenman was singing “A Country Boy Can Survive.” He knew all of the words, but that didn’t make him sound any better. Fred wondered if anybody had ever told him how bad he was.

“I’m gonna stop at the Hot Spot and get me a couple of dogs,” Chickenman said.

Fred could feel the store lights on his eyelids as soon as Chickenman turned in. He wasn’t hungry, but maybe a carton of milk would taste good.

Inside, Chickenman made himself two hot dogs with all the fixins, got a bag of barbecue French fries, a Mountain Dew, and an Iwanna paper. Fred settled for the milk. When the cashier asked if they’d like a bag, Chickenman said, “Yes, m’am. I would. I’d like mine in a poke to go.” Chickenman had good manners around women.

Back on the road, Chickenman ate with one hand and drove with the other. He wanted to know why Fred was so quiet, and how he had enjoyed playing basketball on Saturday and if he really did like watching tennis as much as the NBA.

“Well, are you gonna try to get Schwitzer to hire you?” They were on the Interstate now.

“I would like for them to, but that’s not likely. In fact, they might get shed of me if I don’t speed up.” Fred placed his hand over his belly. The milk felt good in his stomach.

“Get shed of you? That ain’t gonna happen. How many parts did you get tonight?” Chickenman was wadding up tissue paper from his hot dog.

Fred could smell the onions. “Eleven hundred.”

“And?”

“Digger said that Randy thought I should be getting fifteen hundred.”

“Listen!” Chickenman kept rattling his hand around in the paper sack. “I have been in that plant for eight years, and I can tell you they are not going to let you go as long as you keep doing as good as you are.” The Blazer vibrated and hummed louder as Chickenman accelerated up a hill.

“The first night they put me on those balancers, I did seventeen parts all night long, and six of them were scrap.” Chickenman’s voice had slid into a drone that made Fred’s eyelids heavy.

“You’re supposed to balance eleven an hour, and they didn’t fire me.” They crested the hill where lights from the Grove Park Inn sparkled in the distance.

“I’m telling you man. Don’t let them play with your mind and make you crazy. You’re just as damn good as anybody in that place.”

The Blazer began crossing the bridge that signaled home for Fred even though he wasn’t quite there yet. High over river and railroad tracks, this bridge juiced the vehicle with a different sound. Fred couldn’t tell if the pitch was lower or higher. He simply noticed the change, a muffled roar that jabbed its way into his brain at night once his body was worn down. He drank his last swallow of milk, then smashed the carton flat.

“You’re mighty quiet,” Chickenman said.

Fred squinted, for a bath of white lights were flooding the concrete bridge now. He was swallowed by the brightness and needed to soak it up. If Chickenman wouldn’t think him nuts, Fred would have him stop right here. He’d get out and walk around. Just for a minute. He started chewing his bottom lip to keep from blurting out such nonsense. He glanced down at the water, at the old houses and businesses. Dark as it was below, everything seemed to catch a little light from here.

“Better be glad,” Fred said. “And don’t worry about them making me crazy because I’m already that way.” He smiled to himself as they came off the bridge and headed for the next exit.

Tags

Tony Peacock

Tony Elton Peacock grew up on a farm in southeastern North Carolina. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1984.