The Tea Belt

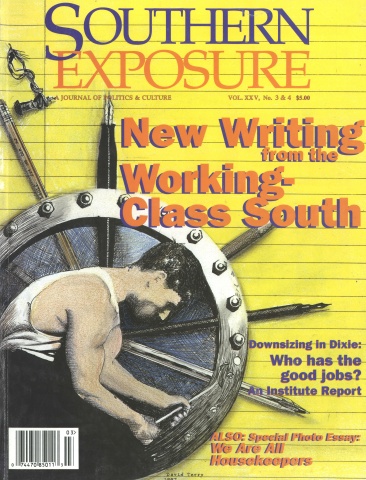

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Supermarket shelves are stacked high with bottled and canned ready-to-drink teas, most fast food menus feature iced tea and health food stores sell teas that claim to cure everything from the common cold to work stress and hangovers.

“Tea is in a renaissance,” says Joseph Simrany, president of the Tea Council of the U.S.A., “and the South is the king of tea.” As a region, the South consumes more than 40 percent of the nation’s tea in pounds, and nearly 35 percent of the population drinks tea — more than in any other area of the country.

The tea-drinking trend is spreading across the country, but for centuries the South has taken the lead on tea. Tea-drinking Native Americans introduced European settlers to their yaupon brew. In the 18th century, tea was the principal drink of the British colonists, who imported Bohea tea from India via England.

England’s attempts to tax the beverage sparked protest, including the famous Boston Tea Party and the less-publicized Edenton Tea Party in North Carolina. Fifty-one women in the coastal town of Edenton signed a declaration in 1774 to help the “publick good” by consuming only local products. They are reputed to have dumped their cups of Bohea tea out of the window of their hostess, Penelope Barker, and replaced it with an American-grown raspberry brew.

Today, tea is still a symbol of protest and an issue for debate in the South. In 1992, as many as 300 Floridians protested rising taxes by mailing tea bags to Gov. Lawton Chiles’ office. The debate over iced versus hot and sweet versus unsweetened may never end, but numbers show that at least 80 percent of the population is drinking it cold and much of that cold tea is sweetened. For born and bred Southerners, iced sweet tea can’t be beat, and new arrivals search, often in vain, for the hot or unsweetened variety.

A new debate over the health effects of tea is also brewing. Some consumers have attributed stomach problems to tea, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have said poorly cleaned tea making equipment was probably the culprit, not the tea itself. Tea has more often been touted for helping to reduce stress, improve oral hygiene, cure cancer and enhance cardiovascular functioning. Researchers in Iowa have even explored using tea to neutralize the stink of hog manure on factory farms, a major problem in southern states such as North Carolina.

Most tea is still imported, but there have been efforts in the South, where the soil and temperatures are perfect for growing the leaf, to produce its own. Andre Micheaux introduced tea plants to South Carolina’s Middleton Place Gardens in 1799. Charles Shepard’s Pinehurst Tea Plantation in Summerville, S.C., was home to the first successful domestic tea business; its oolong tea won first prize at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. In 1963, Thomas J. Lipton, Inc. created a research station on Wadmalaw Island, S.C., with the remnants of Shepard’s plants. A series of experiments cultivating the plants and the development of a mechanized harvester to cut labor costs made American-grown tea a reality.

Today, Lipton’s business has been bought out and converted to American Classic Tea. While a few other domestic tea operations are trying to get going, the South Carolina business is the only one that has become commercially successful. American Classic Teas has taken off, especially in the South. “Most of our distribution is in the South and sales are rising,” says the company’s Sarah Fleming McLester. “The South is where you want to be to sell tea.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)