This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

She could see the curve in the road ahead, pressed between the rock of the mountain on the right and the brown, diaper-coated river bed on the left. Unlike most curves that seemed to narrow and squeeze, this one expanded where she needed the most space, an extra foot to maneuver, more depth of vision to prepare for the bulldog coming at her on the Mack truck. In the winter, icicles lined the curves. When night air got below freezing and the next day’s light hid its face on the north side of the mountain, dripping water stopped in long exclamations. Now the days pushed away the long hold of the night. Lavender shells of crocus began to uncurl their lavish, inner selves.

Her English 101 instructor, Mrs. Turpin, said, “You’ve got to believe in yourself. You’ll never know if you don’t try.”

Darlene wrote that down in her yellow spiral notebook to read against the nights when she had a paper due the next day, when words stalled somewhere between her head and the paper. That terror of the night, that knowing she was wrong, that she had made a mistake, came at her more than she would ever say.

She had passed the G.E.D. when the boys were little; now they were almost as tall as she. Here she was at 33, the same age that high blood claimed her own momma. Here she was, taking a night class, going to college. Those last words, going to college, curved through her mind, the way the car followed the road without a guard rail. She thought of suns and moons, unknown planets, and wished for the certainty of the orbit. If she failed, Butch would look at one of his buddies and give a long, knowing wink.

The trailer felt steamy with a stuffiness that begged for relief. Fake wood paneling sweated a mixture of humidity and frying pan grease. Before Darlene started the hamburgers, she went from window to window, clicking the latches, pushing up on window frames that stuck. She had finished a five-hour shift at Wal-Mart and had the night to reread a chapter about process essays, to begin again with her composition. Her green shirt with the tiny flowers felt sticky in the armpits; she fanned her face with one free hand.

“Don’t you know how hot it is in here?” Darlene said to Butch.

“What’s it to you, if I like it hot?” Butch’s chest looked pale, unprotected against the attack of brown, spiraling hairs. A false impression, for he knew no fear. His rounded stomach rested easily above his lap while one hand held the remote control: the entrance to his kingdom.

“It’s fuel oil,” she said. “That’s what it is to me. I pay the bills, remember? I’m the one who goes to work, if you want to get exact.”

In the middle of winter Butch sat around shirtless, with his Old Milwaukee. In the summer he pulled on a plaid short-sleeved work shirt over his white tee shirt when he worked on his truck. That’s what he did all day: lifted the hood, said things, rearranged mysterious parts, all in the name of fixing things. Sometimes a neighbor brought his truck too, and they had long conversations, Butch’s foot propped on the front fender. Butch would tinker around for a couple more days. If money was exchanged, Darlene never saw it. All she saw was the grime in the creases of Butch’s finger. At night when he told her to come to bed, she submitted, but the pleasure was gone. She had learned long ago not to expect pleasure. Placing her body next to his was a duty, like making cornbread every day.

Back in the boys’ bedroom Billy Joe was on his hands and knees, raving at a creamy mush of cockroach he had concocted. “Gaw! Look at them guts!”

“Hey, that’s my sneaker!” Pooch grabbed the shoe with the red and black swirls that tailed like comets. The laces flapped against the brown folding chair as he lifted the shoe by the tongue and held it above his head. “Use your own shoe next time and clean up this muck,” he said. Darlene heard a fast-moving body and saw the screen door bounce open behind Billy Joe. Pooch could never catch his younger brother. His words were never tough enough and, with the way Pooch devoured hot dogs and RC’s, he would never match the slight one on foot.

Her teacher said, “Think, think, all the time. While you’re ringing up someone else’s Hi-C and Fruit of the Looms. Think about ideas. Think how you can surprise with that unexpected opening, how you can wrap it all up with that unexpected opening, how you can wrap it all up with a kiss for the reader. Say goodnight. Think, think, think.”

Mrs. Turpin has surely never worked at Wal- Mart, never had to smile cheerfully at customers asking for K Mart’s sale price on tape cassettes. For that matter, Mrs. Turpin surely didn’t go home to someone like Butch either. She probably went home to a man wearing cuff links and a green and gold paisley tie, someone who fixed lettuce salads at a butcher block and whistled, yes, he would whistle violin music. Darlene loved watching Mrs. Turpin write with her left hand, seeing words form with all their grace in that slight downhill slant. It wouldn’t have surprised Darlene if Mrs. Turpin arranged words from right to left, with a result that still made perfect sense.

Going to college, going to college. But what Darlene cared about most was Kelly and the boys. Darlene didn’t need to be a modem woman and leave her husband to be happy. She would put up with Butch, find her own ways around him. Mrs. Turpin never had to consider such a thing; Mrs. Turpin had an outline for her life.

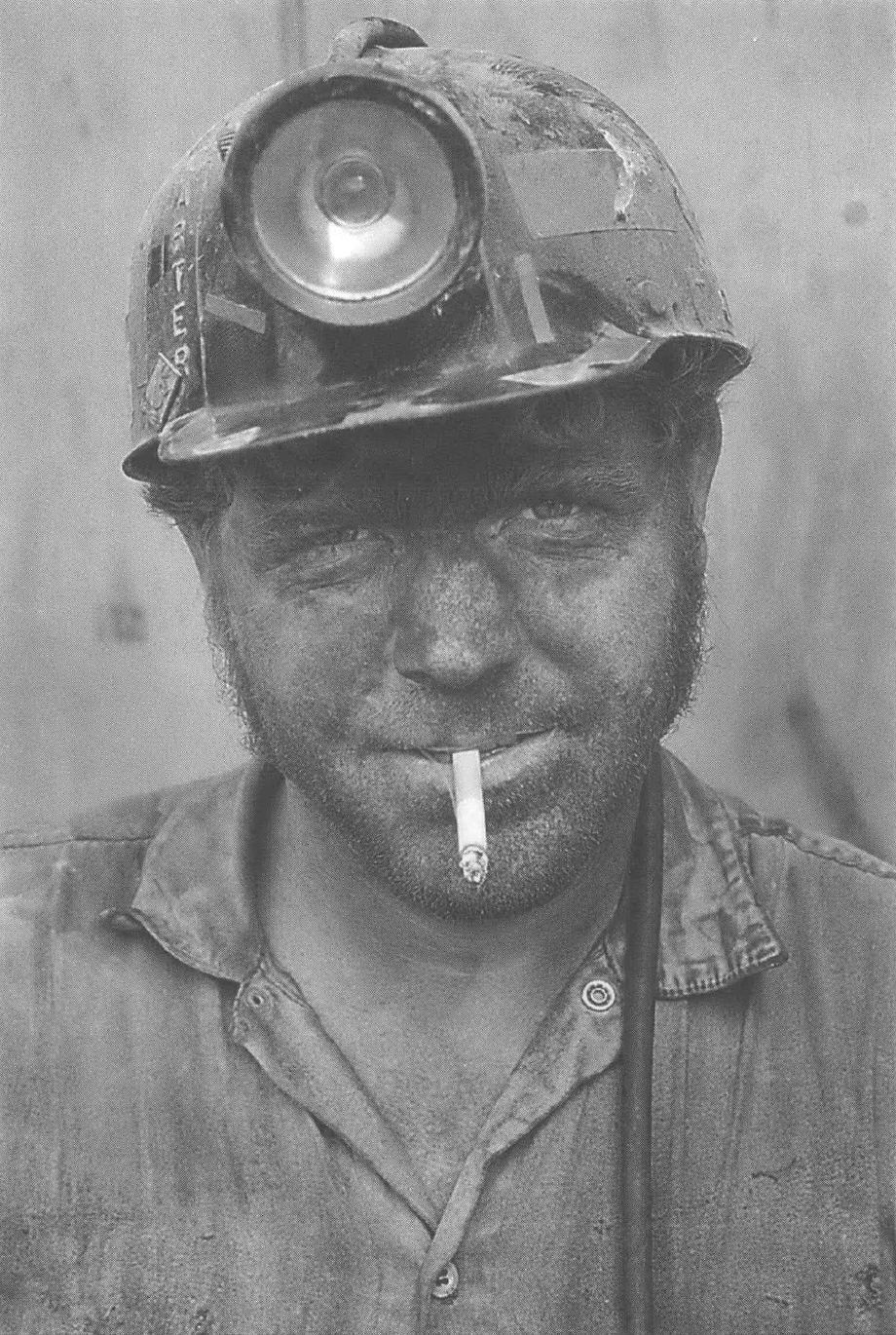

Maybe it wasn’t all Butch’s fault that he was as useful as an appendix around the house. These were hard times for all the men in the community, so many mines shut down. He must miss those heavy, male machines blowing black dust over his face, digging into the earth and leaving a mess. All he could manage now was to wear his toughness on his hands. The world might be changing for Darlene, but Butch’s outlook stayed as stuck as his haircut. He would never lose the nickname, never part with his notions about the way things ran.

“You got some people, the ones that got the power — the mine operators, bank presidents, head honchos, that sort — and then you got the rest of us,” he said. “Now the rest of us can suck ass all day or just let the rest of the world chase itself.” Butch pointed his fork at Darlene and continued, “So, Darlene, what’ll be for you? Huh?”

If Darlene refused to answer, he turned to each of the kids — that’s what he called them — or to his momma, Maggie, who lived just a block away through a couple back yards. They all got the same treatment until he wrestled a satisfactory reply from someone. That was the only thing he bothered Kelly about; he would pursue her for an answer just like everyone else.

Kelly was Darlene’s, born of the man before Butch. Darlene could admit now, the first one had been little more than a gangly boy looking for an experiment. When Butch was heavy with his need for her and badgered her with his importance, all she could say was that the details of past men needn’t concern him. She made him understand that Kelly, only three years old at the time, came with the package. And Kelly was hers.

Through the years no one doubted Kelly’s origins. The light brown hair kept getting darker like her mom’s; the eyes played the same green and brown tricks. When she was twelve, she carried her body the way Darlene had worn her own adolescence — on straight, thin legs, lifting a flat stomach and a barely noticeable bust. Darlene remembered despairing of ever having anything to show a man, just as Kelly had wailed, “Mom, I hate it; I’m so small.”

Darlene had hugged her and smiled, “Just wait, Peaches. It will come. Some day after you’ve had your own little ones, you wish again for slimness.”

Now at sixteen Kelly was still the image of her mom. Darlene had made all the decisions for Kelly, knowing where there was enough money for gymnastics and what kind of ear rings she could wear — grateful that Butch had not interfered. Men didn’t know anything about those things anyway, so Butch’s disinterest didn’t mean much. He never wasted time on what was unimportant; he saved his energy for crankshafts. Darlene understood his indifference as a sign that someone else’s seed in the house insulted him. “Girl stuff,” was all he said, but then no one looked to Butch for psychological depth.

With the boys he responded differently, taking on Pooch and Billy Joe as his children, as if they were lucky to grow up under his mark. It didn’t matter that Darlene was their mom. It didn’t matter that she wanted a set of World Books to help all of them do their homework. Butch only cared that his boys could change the spark plug on the lawn mower, that they went with him on Saturday nights to watch chickens — decked out in spurs — fight for money. Darlene could not bear to hear him deride the boys because of her — “Your mom thinks you should know fancy words that are too big for average folks to pronounce” — so she had handed them over to him. If some of her genes survived, the boys would have to discover that for themselves after they were out of Butch’s shadow.

He had laughed when she first mentioned a night class through the community college. “Get real! You can’t do that.”

She hadn’t honored him by bothering to ask why he thought she couldn’t. But she was careful to leave her registration form on the table where he could see it. His response came quickly, “You’re crazy, you know. You’re really going to do it, aren’t you?” She chose not to think of this as a question, folding the tuition receipt and tucking it under the unpaid bills. She was the one who earned the money.

That was back in the early days of January. Now the semester was in its third month and she was still alive. She had survived those first weeks, when Butch looked to be right. “You won’t make it,” he said. He kept the television volume higher than usual, so that everyone had to shout to say anything.

The words of the textbook mushed up in her head, the words that marked her entry into a world beyond cleaning up after others. Mrs. Turpin stood there in black and white, telling her to find a seat up close. She had found refuge behind a large body two-thirds of the way back into the middle row.

Butch’s ridicule had blown open before the boys. “Your mom wants to think she’s smart, like a lady from Chestnut Estates who wears men’s jackets and prances around with a briefcase in her hand. She’s too good for us.”

The boys had squirmed and re-read the backs of cereal boxes. Darlene kept her back turned and fried the sausages extra hard, the way Butch liked them. She took care to fix all his foods as he wished — thick fat back in the soup beans, bacon burned beyond crisp — nothing to hint that going to college affected her performance at home. She kept her brown hair, straight, long and clean, like a faithful church woman. When he went to bed, she went to bed. But she would not let him touch what was in her head.

In the last month he had stopped his mocking. Instead, there were other words, that jabbed like empty knuckles in the air, “Your kids are losing out! They don’t have a mom anymore.” Or sometimes, “The boys didn’t used to fight like this. Something’s eating them.”

Even with his brief tirades, Darlene felt strangely justified. She had proven she could write essays — “stories” as Butch insisted on calling them — and still keep them all in socks. She could show Kelly that a girl didn’t need to repeat her mom’s mistakes, that another world waited to be seized by people in skirts. If Butch had to rely on his momma’s cream pies more of the time, let him. They were just store-bought banana cream and seemed to bring Maggie a sense of accomplishment, as if supporting Sara Lee indicated entrance into the upper class. There was no need for Darlene to duplicate that. Maggie had never given up her son anyway, insisting he come for chicken and dumplings ever Sunday. And now Sara Lee was invited too.

Another thing Darlene would admit, she liked the way Butch took care of his momma. She hoped Pooch and Billy Joe could see his tenderness toward her, even if it was awkward — the way he drove his momma around in his brown Chevy S-10, waving great big to everyone, taking her to get groceries or pay her taxes at the courthouse. Back in November he spent a day putting plastic on the windows of his momma’s house. Of course, he waited to wrap up their own trailer until there was snow on the ground and expected Darlene to pity his stiff fingers in the wind.

His latest tactic didn’t really surprise her; fixing her children in her mind and then placing slight shadows beside them. His words echoed in her mind as she read about transition sentences. Maybe Pooch has an eating disorder. Shouldn’t she take him to Dr. Nomer? And when Pooch was suspended from school two days for cracking another boy’s lip: wouldn’t it be better if he saw his mom go to prayer meeting on Wednesday nights, instead of seeing her sitting there flipping through that old dictionary? Didn’t Darlene have any jobs for the boys? They came home from school, grabbed Twinkies, and roamed the neighborhood like young pups until dark — hard telling what they might be getting into.

And Kelly — Butch didn’t mention her, but Darlene had to admit she was slipping away. Kelly rarely spent time in the kitchen anymore, unless it was to fix Butch a pudding. When Darlene asked Kelly about her home ec project, all she got were one-word answers: no, maybe, huh-uh. Darlene felt Butch’s eyes on her, watching her reaction. An angry stone inside Darlene wanted to ask him why he couldn’t set the table, why she always had to be the one to coax Kelly out of her room, but she knew it would be pointless. Butch knew the rules; he made them.

If she could only keep her family together for five more weeks until the semester was over, then the proof would be clear. She would have all summer to say those words to people: going to college. Last week Maggie had called, telling her about a shower for the Wheeling girl. No, Darlene had said, she couldn’t make it, but she’d be sure Kelly was there. Let Maggie sniff. There was a notice of a potluck for the new Baptist minister and his family. Darlene would have to wait until summer to learn to know them. Yes, of course she believed in the resurrection, but she didn’t have time to dye eggs this Easter.

Darlene was rearranging her life — Mrs. Turpin liked to talk about priorities — and people could either move with her or, if they preferred, stand there clutching their corner of the blanket. She was changing, for herself and for Kelly. The world didn’t have to be the same as when Darlene grew up. Anyway, the world wasn’t the same. Her own life would make a difference for Kelly; she would show them all. Butch could stay slouched on the couch; that didn’t mean she had to sit there, rotting away beside him.

The woods, dry and brown around the trailer, lay heavy with last fall’s leaves; underneath, the earth nursed green stems of blood root and violet. Patches of wild, blue phlox gave no thought and tossed their fragrance into the air. She could smell them; there was no holding them back. They pushed down hillsides, raised their heads along roadsides and around curves. Spring was a time for letting go, not pulling in.

Mrs. Turpin said, “You all look tired. But think what you’ve accomplished. This isn’t the time to quit or get careless. Ask your husband to fix dinner. Only two more papers.”

Dinner. Butch would wonder what that was, unless it was Sunday. But two more papers to write, that wasn’t so bad. If she could just hang on, be a survivor, Darlene would deal with Kelly’s withdrawal when her own pressures had eased up. She would sew her a jumpsuit of denim, like they had seen at McCarty’s, and win her back. It wasn’t wise to push Kelly for answers now; Darlene might say things she regretted later. Kelly would be alright. She was just backing off, like most teenage girls needed to do some time or other. She would come out of her unspoken reproach and they would laugh over Roseanne again. It had to be. Four weeks later Darlene sat at the kitchen table, using the silver tip of her ballpoint to trace the green pattern of vines on the oil cloth. She had never studied for a final exam before and the thought of all she could be asked to recall terrified her. Terms about writing, ideas about organizing principles and methods that were dark secrets four months ago skittered through her mind. She thought she had a definition memorized and then it rolled away. She had risked the security of life with Butch, only to come to this. He offered her little — a dumpy trailer, scuzzy television heroes — but at least the end product was predictable with him. Some days it was unmistakably clear to Darlene: she had come this far, only to fail. Her finished papers mocked her, the B’s and A’s were all mistakes; somehow Mrs. Turpin had not detected the sham in her work.

Yet for tonight, she would not give up. She would keep herself calm and not allow any interruptions. If there was a disturbance, she would send Billy Joe and Pooch to their room. She had worked so hard — too hard perhaps — she might as well endure a little longer. She would take the test, see where she stood. Mrs. Turpin was so sweet — might even be disappointed if Darlene quit — said to think about trillium, not dandelions. If Darlene could finish 101, there would be another writing course to take, tougher of course, but if she could get into Mrs. Turpin’s section, another miracle might happen. By then, she could believe and Butch would have to shut up. Or go live with his momma. Darlene understood the principle of a stone rolling downhill. There would be no moss on her by the time she was finished.

A couple hours later she laid her head down on top of her arms, folded like a small fort on the table in front of her. She rubbed oil off her forehead; her lips moved dryly over the hair on her chapped skin. All the words of the semester bunched themselves together into a sphere and crowded together, leaping out of her brain, off her arms, off the table, down to the floor and out the door, pushing and rolling past the dogwood, around and down the curve into the still murky river bed. She heard a round plop against the rocks, saw dirty water briefly slosh.

Butch was shaking her elbow. “Hey! Darlene! Kelly needs you; she’s back in her room, crying like a goon. You . . . here . . . sleeping . . . didn’t even hear her.”

Darlene tried to make sense of the look on Butch’s face. He was the parent; she was the child. He kept poking her with his greasy fingers. What had he done that made him look like he had stolen up on triumph? She could hear Kelly crying, helpless in her crib, wanting her mother.

Darlene got up from the table and bumped against the wall, then walked down the hallway as she had seen people lurch on moving trains in the movies. At the last bedroom, Kelly’s door was closed, but the short whimpers continued. How long had she been like this? How could a teenager pretend to know grief?

Heat still hung in the trailer, a hint of the clammy summer to come. A street light shone through the torn screen door, casting strange swirls over the cheap wood of Kelly’s door.

“Hey Kel!” Butch called. “Open up. Your mom’s here. She woke up. Might as well get it over with.”

Darlene’s mind fixed on the word “Kel”. Butch called her “Kel”. When had that started? She had never heard that before.

Darlene leaned against the wall, her arms folded in front of her, supporting her sagging breasts. The trailer swayed a bit; then righted itself. She crossed one leg in front of the other. Whatever it was, she could handle it. Her final exam was in two days and she had an eight-hour shift tomorrow.

“Come on, baby,” Butch called. “Don’t make me break the door down. You know how your daddy gets when he’s mad.”

Darlene could see the sphere rise out of the water, swing crazily against the curve, gather speed and size as it rolled up the driveway and stopped outside the trailer. It had become a stone at the tomb again.

She didn’t need to look at Kelly, didn’t need to glance at her once childlike shape. Darlene knew, could see the softening and rounding, the hint of broader curves. It was all there and Darlene had missed it. Supplies untouched in the bathroom. Leaving for school without breakfast. The silence. Where had Darlene been and for what reason?

Darlene slowly lowered her body to the floor, her knees scrunched under her chin. It might be awhile before Kelly answered.

Once more Butch yelled, “Come on, Kel. Your mom doesn’t have all night; she has things to learn.”

Darlene looked up and caught the light on the half of his face that glanced down over her, the half that ended in a long, slow wink.

Tags

Evelyn Miller

Evelyn Miller lived in Southeastern Kentucky for 19 years. She has worked as a high school teacher and is now a teaching assistant at Ohio University (Athens) where she is working on her doctorate in English. (1997)