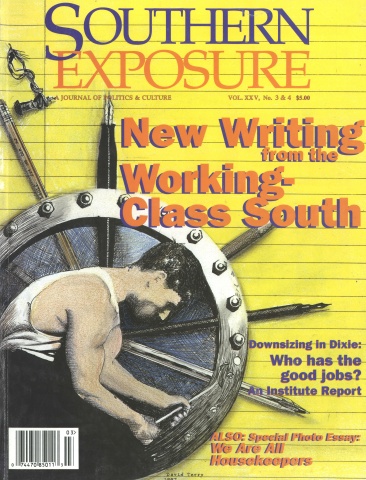

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

I still cringe when I have to write a bio. My introductions at readings are embarrassingly short. I shrink away from the guests at cocktail parties and I try to dodge the questions about my schooling. Not because I am ashamed, but because the questioner always seems dumbfounded to learn that I never attended college. The usual response is a change of facial expression, something like admiration to fear, followed by a brief recovery, a pregnant pause and a story about a friend of a friend, who knows someone, whose daughter didn’t go to college. It’s a well-intentioned story, told to keep me from feeling like a freak. But I am a freak. Go ahead and say it.

If the conversation progresses, I am often asked why I didn’t go to college. I suspect that the questioner is thinking that there will be an interesting story, something they can tell their kids over dinner to show them how lucky they are, something about me being the oldest of twelve children and how my parents worked second shift at the auto factory and I grew up in a tough, gritty environment but my home life was good. A sort of “I pulled myself up by the boot straps,” Americana kind of story. But the truth is I hated school.

School Daze

School was oppressive. School was beige walls and beige lockers, grey linoleum and concrete steps. School was the jarring ringing of bells and the smell of ammonia that the bathrooms were drenched in to keep a few errant kids from smoking there. School was teachers policing the halls and herding us to mandatory pep rallies. School was a depression that seeped through the very pores of my skin and lodged itself in my bones.

Every year I swore that it would be different. Every year I had a brand new notebook with a virginal blue cloth cover. I had new pens and pencils sharpened to a dangerous point. I was ready to excel. But I never did. I never could. All I could do was wait for the final bell to ring, wait to smell fresh air, wait to get home and change into my jeans. When I look back it seems like a jail sentence. It’s a blur that lasted twelve years.

I survived school by day-dreaming. I still find myself doing it. If I feel trapped and bored my eyes are pulled towards the nearest window and my mind takes flight. In grade school I would imagine myself leaping from the roof of one building to the roof of the next, as if I were a wild jungle child. In junior high the fantasies changed to include cute rock stars and long blonde hair.

As I entered tenth grade, high school, the official last leg of the public school journey, I found some relief. Three significant things happened. I was now allowed to wear jeans to school. I smoked marijuana for the first time. And I discovered skipping class. Soon whole days were spent away from school. Why hadn’t I thought of this before?

Crossing over to the wild side of life brought me something besides free time, a more comfortable wardrobe and an enjoyable recreational drug. Suddenly I had friends and my day-dreaming had a qualified name: “Getting high.”

If it had not been for skipping and drugs I could easily say that the entire twelve years of school were the most miserable of my life. The only other things I have done for equally as long are writing and smoking dope. I kicked the pot, but not the writing.

Towards the end of high school my mother brought up the subject of college, even though my grades were hideous.

“I am not going to college,” I announced. “I hate school.”

I was assured that college would be different. I was assured that I would enjoy college, have more freedom, more choices. But I wasn’t buying it. And why should I?

Weren’t these the same people who asked us to climb under our desks in the event of a nuclear attack? Weren’t they the ones that put the boys in shop and the girls in home-economics and never the twain shall meet? Weren’t they the same people who told me that being an introvert was bad? Hadn’t they failed to mention Benjamin Franklin’s plethora of illegitimate children or Thomas Jefferson’s “alleged” slave lover? Why would I believe these people when it came to the subject of college? Why would I believe them at all, about anything?

I can’t say that I was exactly eager to enter the work place but I couldn’t see another four years of school. I couldn’t spend four more years cramming my 5’10” frame into a too small desk. This sums it up. Nothing fit.

When my mother learned of my plans to avoid college she strongly suggested that I take typing, so I could be a secretary. This was the only option that was presented to me. Trade school was never brought up. I didn’t even know it existed. It was never suggested to me that I take a year off and decide later. When I said I wanted to be a writer, I was told, “You can’t.”

Blue-Collar Blues

So, at age eighteen, I entered the blue-collar world. I entered kitchens and bars and dairy barns. I found people with weathered faces, swollen feet and rough, callused hands. I handled big jars of mayonnaise and fifty pound sacks of flour. I learned how to budget, how to wash my clothes and how to get out of bed in the mornings. The working environment was the first place that I ever felt smart.

Over the years I have worked as a waitress, a clerk in a drug store, a bartender, a milker at a dairy farm, a carpenter, a locksmith, a drum maker, a house cleaner, a house painter, a house sitter, and whatever else it has taken. Some jobs have been harder than others. Through trial and error I learned that I just wanted to go to work and come home. I didn’t want to go into management. I didn’t want to spend my time studying products. I didn’t want to go to meetings. I didn’t want to kiss ass. I just wanted to write, go to work, come home and write some more.

I am still at it. And I celebrate the innate knowledge I have always had of myself. Even at a young age, I knew that my body was resilient but my soul was not.

Soon I had another problem and it was not work or writing. The problem was what to call myself, what label could I draw up when asked to identify myself, what to say when a stranger asks, “What do you do?”

What did I do? I wasn’t in school. I wasn’t raising a family. I wasn’t the head of anything. What exactly was I doing? What was the one thing that could be pointed to as the justification for the air that I breathed and the food that I ate? What was my productive, well-adjusted role in society?

When faced with this question, I felt that I had one of two options. I could either say, “I sling burgers down at the drive-in,” and risk being immediately thought of as stupid and boring, or I could say, “I am a writer,” and risk being called a liar.

It did not matter that I was, at that time, accumulating pages in an old notebook with duct tape strapped across its binding. It did not matter that I began my days anywhere between 4:30 and 5:00 in the morning, just so I could sit at the computer for an hour before work. It did not even matter that I was well read and had a few short stories published. The book was the thing.

So day after day, page by page, sentence by sentence, I finally filled that old notebook. After a series of rejections, an offer was made. I negotiated a contract. I received a small advance. I went to a hypnotist three times so that I could deal with my fear of speaking in public and I surfed a big wave, the book tour.

High Society

The book tour led me, oddly enough, to the very places I had always hated: Schools, colleges and classrooms. The walls were still beige. The linoleum was still grey and the steps were still concrete.

At cocktail party after cocktail party the questioning continued. “What is your book? Where do you teach? What school did you go to?”

I am assured over and over again, by well-meaning people, that a college degree does not matter, but if it doesn’t matter then why do people keep asking? And why am I always the only non-academic on the panel? And why have I been advised to keep quiet about it?

At a conference that I recently attended, I was so nervous at being on the stage with so many accomplished writers that I decided to tell the truth about myself as a remedy to my fear. I stood in front of the audience and told them that I had never been to college, that I worked in a grocery store, that Life Without Water was my first novel and I was hard at work on my second one. Energized by my truth telling, I then proceeded to give the reading of my life.

Over drinks that evening one of the other writers, a very degreed gentleman, asked me why I had told the audience that I had not been to college.

“Because it’s true,” I said.

“But if you hadn’t told them, they would have never known.”

“That’s why I told them.” I answered, still not getting his point.

“What I am saying,” he replied, “is that I don’t think anyone is interested.”

Ah, so that’s the point. His education is interesting but my lack of one is not. His history is interesting and mine is not.

Well, I disagree. To suggest that I hide my past is to suggest that there is something shameful about it. It is also to suggest sure failure, because if I can’t be me, then what’s the point? I didn’t become a writer in order to lose my voice.

His comment only proves to me that I need to keep on being belligerent. People need to know that writing belongs to all of us. They need to know that blue-collar writers exist and are not stupid and they need to know that we have important things to say, are interesting people, and that the guy who cleans the pool just might be writing an epic saga about them. Furthermore, they need to find something else to talk about at cocktail parties.

At the very beginning of my career, I would have fallen down on the floor and cried if an author had stood at the podium and said, “I have never been to college and I am a published novelist.” I would have bought that author’s book over anyone else’s.

Because every time I attended a conference and heard an author’s degrees listed before a reading, what I was really hearing is, “This is what you need to be a writer.” And that was exactly what I knew I would never have. And now I feel lonely because I don’t know who my peers are.

I was told, after publication that a book could get me a job, teaching fiction at a university. What the hell, I thought. Why not try? I can write and I’m sure I can give my knowledge of writing to anyone that really wants to learn. Plus I needed money. My savings were depleted from all the work I missed while out promoting my book. And a good health insurance policy would not have been a bad idea either. So I called.

“Send us your vita,” the man said.

“What’s a vita?” I asked.

There was that pregnant pause again. Finally he answered, “A resume. Your publications. Where you’ve taught. Your schooling.”

I came clean with my lack of college, if he hadn’t guessed it already and I suspect he had. He had not heard of my book. But that’s okay. I had never heard of a vita.

“How did you learn to write if you have never been to college?” he asked.

I almost laughed. I learned how to write the same way that college students learn. I had a love of literature and I read and I wrote and I asked other writers what they thought and I listened. And I did it over and over and over again and it will never end. It’s the same process that all writers go through. Some of us got through it with editors. Some of us go through it with writer’s groups. Some of us do both.

Perhaps one of the other reasons I considered white collar employment was the trouble I felt on the other side of the tracks. One of the hardest things about promoting my book was the sudden juxtaposition of roles I was playing, one night being escorted in a limo and taken to a country club for dinner and the next day schlepping potato salad to Yuppies with cell phones. One day visible. The next day not.

Once visible the return to invisibility (read: blue-collar work) is especially hard. Fifteen minutes of fame is a dangerous thing.

Add to that the reaction from co-workers and customers.

“You’re going to be rich.”

“I’ve never known a famous author before.”

I’m not famous and I’m not rich. Presently, I have to work for a living. But where can I find a job that is flexible enough to allow me to go trotting off to readings and workshops, pays well enough that I don’t have to work full time and doesn’t kill me? As a blue-collar artist, I feel myself straddling two worlds that are spreading farther and farther apart.

I know that my road to becoming a writer while living a working-class life has actually been an easy one. I grew up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which has a well established writing community. I have managed to access some of these writers and to wheedle my way into workshops and classrooms and to get noticed and get help.

But how do my fellow blue-collar writers who live in less academic settings get help? Where does a steel worker go for a class on characterization or plot? How does a plumber who is bursting with stories begin if college is not a chosen option and they have not been born in a town like Chapel Hill?

And why do most educated people believe that, across the board, blue-collar workers are not articulate and that our only interests lie in beer and sports and cars? Why do most educated people believe that a degree proves something about a person’s character and their ability to carry on an interesting conversation? If America was built on sweat equity, which is what I was told the few times I listened in school, then why are there so many untold stories? Why do I feel invisible the minute I put on my blue-collar hat?

I personally want to see a movement, a revolution. I want to see writing returned to the masses. I want the working class to know that there are writers among them. To know that writing, expressing yourself, story telling is not just for the college educated, but for everyone. And I want academia to know the same thing.

I want to see panels composed of nothing but blue-collar writers. I want to see classes offered in churches and libraries and living rooms. I want there to be grants (plural — grants) available only for working class writers and I want the entries to be judged by their peers, by other blue-collar writers. Because I want to be judged on the strength of my writing, not the strength of my grant writing.

I want these things because I need them and because I’m lonely and because I’m tired of answering that string of questions, “What’s your book? Where do you teach? Where did you go to school?” I’m tired of seeing the faces of my hostesses change briefly when I reveal my history.

They want proof. Proof that I deserve the label of writer. Proof that I deserve to be served stuffed mushrooms on a silver platter. Proof that I deserve a second glass of bubbly and that I won’t be getting too drunk.

At these functions, I want to plump the pillows and pick up the abandoned paper cups. I want to restock the ice, swirl the cocktail napkins with a mixing glass, tidy up the fruit salad and move the centerpiece so that it covers the water stain on the tablecloth. I feel like escaping, slinking along the edges of the room and slipping into the kitchen to talk to the help. I feel like putting my jeans back on and getting out of the too small desk. But where do I go?

Tags

Nancy Peacock

Nancy Peacock’s first novel, Life Without Water, was a New York Times Editor’s Choice for ’96 and was reviewed favorably throughout the country. Nancy has had short stories and essays published in journals such as The St. Andrew’s Review, Sojouner, and The O. Henry Festival Stories. She lives and writes in Chatham County, North Carolina. (1997)