Making Change in a Closed Little Town

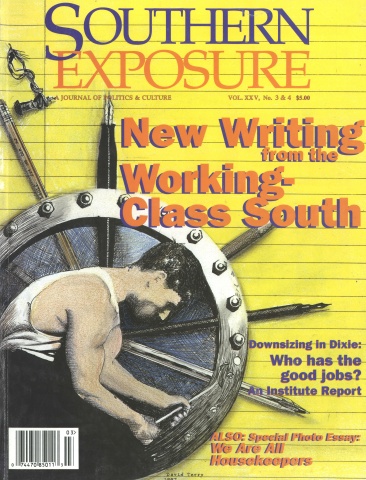

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Sarah White lives in Moorhead, Mississippi. She is currently on leave from her job as a worker at Delta Pride Catfish in Indianola, and is working as a union organizer for United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1529. Along with Margaret Hollins, another Delta Pride worker, Sarah is writing a book on their decade-long organizing struggles in the catfish industry.

What everybody knows about me is that I’m a catfish worker and a union organizer. Ever since the 1990 strike at Delta Pride Catfish, I have traveled to other parts of the country to tell the story of our struggles in the Mississippi Delta. But our story isn’t just about how we won that strike, the largest strike in the history of the state of Mississippi. Even more, it’s more about how to make a change in the mind, in how workers think about themselves and what they can do. That’s why Margaret Hollins and I, two Delta Pride workers, decided to write a book about what we have experienced.

I know what I want from this book. It’s a picture painted for other workers in the same situation we’re in, a picture for those who could play a part and change their situation. Being in a poor area, having strikes against you as a woman, or even just as a worker, a Black worker, makes you see that our struggle is to make a change. The struggle is not just to prove you can fight or defeat the company. This struggle is about cleaning up and straightening things out to make a better way for your children, to make a better way for other people’s children, to make a better way for people as a whole.

We were in a situation at Delta Pride, in Indianola, Mississippi, where things seemed that they never could change. But they did change. Painting a picture of how it used to be, of what we did to change things, can give workers a sense of doing something about their own working conditions. That’s why I say that our main audience for the book is the people who are down in a situation like us.

In the early 1980’s we were living in a closed-in little town like so many other areas of Mississippi that closed. When I say Indianola was a closed-in little town, I mean it was a town where you didn’t question whatever way the man wanted things done. Even after the civil rights movement, it was still true that the people in power had all the say; the white way was the right way when it came to your job. We were told: if you want to keep your job, you keep your mouth shut and do the work.

It seemed like they had control of our minds, that nobody really understood that there was an avenue we could go down to break through to a better place. It’s what we call the “plantation mentality.” To tell our story, I have to go back to that time, to my family and my own growing up in the Mississippi Delta.

A Delta Childhood

My grandmomma, my mother’s mother, had come from Leflore County, from a family where everyone worked chopping cotton, and ploughing the fields. My grandmother was 14 when she got pregnant, and had to go off on the railroad to find a job. Her baby was my mother, her only child. She went to cooking for the railroad, which led her on up to St. Louis, Missouri. There, she got married to this man who worked on the railroad. They got married and raised my momma till she was about 17, when my momma had the desire to come back home to my family that was still here in Mississippi. That’s how I came to grow up in the Delta; it was my momma’s choice.

My momma got pregnant at the age of 18, and got married. She had eleven of us. Two are dead now, so I have five brothers and three sisters. I was born in 1958, so I’m the fifth child. My mother settled in Inverness, Mississippi. My father worked on a farm, with only a third grade education. He’s still on the farm, driving tractors, doing cotton.

When I was a little girl my momma was in a car wreck that left her in a coma for over a month. My grandmomma had to come back from St. Louis to take care of the six of us when her husband, my daddy, walked off and left her there like that. My momma never did get an education. I think she went to school till about ninth grade, though she did take a GED test later. Anyway, she didn’t have any education, my daddy didn’t have any education, and my grandmomma had a sixth grade education.

But my grandmomma always believed that she had rights. In St. Louis, when she worked in white people’s homes, she let them know how she felt about things. She told them what time she was going to clean the house, and how she was going to clean it. They might have been her employer, but it was never just a question of what they wanted.

Stormed Out of Inverness

I was in the fifth grade, 12 years old, in 1971 when the tornado struck my town. There was a popular, outgoing older guy named Peewee, a friend to my father. He loved to party, and he was outspoken within the town. He would take people to the store. Then all of a sudden he got sick. A lot of people couldn’t accept it, he was that popular. They put him in the hospital, and one day he made a statement from his hospital bed, saying “When I leave, I’m going to take a lot of these sons of bitches with me.” I guess he was just trying to spook the illness that he had.

Peewee died soon after that. They buried him on a Sunday. I don’t think it was an hour after they buried him that the storm hit. The tornado destroyed the whole town of Inverness. I don’t know the exact count, but many people got killed. They were laying on the ground everywhere. The Red Cross, I think, came and rescued half the people. We got left behind for about two hours after they pulled the first people out. It got dark again; you couldn’t see anything. Then we got a second storm, this time just a good thunderstorm. My family had to go search for one of my brothers, Curtis. We couldn’t find him after the storm. For three and a half weeks we thought he was dead, but finally we found him at the Red Cross in Greenwood.

To this day, a lot of people say and believe that the tornado hit because Peewee cursed the town. I don’t know if that’s true, but I know there was no place for us to live in Inverness after the tornado. We had to move to another little Delta town, Moorhead.

A Delta Sense of History

When I went to Gentry High School, the public high school in Indianola, in the mid-1970’s, it had already been integrated. But there were very few whites in my class when I entered high school, and less when I left. You could pick them out, maybe three or four in my graduating class. They were the few whose families couldn’t pay for them to go to the Academy, the private school where all the other whites went.

We didn’t learn much that prepared us for the struggle at Delta Pride in that school.

We heard about Dr. Martin Luther King, and how he had a dream about all people being equal. But it was just a dream.

We heard about Harriet Tubman, the woman who brought slaves from the South to freedom, but there wasn’t much stressed on it.

We heard a little more about Fannie Lou Hamer, who led the fight for voting rights right here in Sunflower County.

We knew about different people who were fighting the cause of equality for us. When they had the voter registration demonstrations in Ruleville and in Indianola, I was only five or six years old. My momma knew about them, but at my house survival was the issue. By high school, I knew some more about Black history.

But I never hooked it up to unions. Later, when I started working at Delta Pride Catfish, I got the concept of Dr. King and Fannie Lou Hamer, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and it helped me to know how to defeat a company like Delta. But before then, it never dawned on us that a union was the key to making a difference. All we knew was that if you spoke out like Dr. King, if you spoke out like Fannie Lou Hamer, you were just a fired turkey — or killed.

Skinning Catfish

The first time I worked in a catfish plant was in 1981. I got hired on the night shift at the Con Agra plant in Isola. When I walked into the plant, they explained all their “dos” and “don’ts.” They told me all the rules about being at work on time, about obeying your supervisor. I could see that all the supervisors were white, and all the workers were black, mostly women. They introduced me to my supervisor, the supervisor of the kill line, Bill. He said he was going to train me to be a skinner. I had no idea what a skinner was, but of course I had seen catfish before, so I knew it would be filthy and nasty. I always hated fishing. My aunt used to take me fishing when I was little. She would take me in a boat, and I would be terrified.

Bill took me to the kill line. There was a lot of blood everywhere. I saw people cutting the heads off fish, people taking out the stomachs. He took me down to the last process on the kill line, the skinning, and showed me how to hold the fish. It was slippery and sharp. The skinning machine was on, and I dropped back because I was scared of it. As good as it could take the skin off a fish, it could take the skin off your hand. But I knew I had to do this job, I needed this job. So I learned to be damn good at skinning fish.

I could learn any job, but I still had a big problem in my life. I was the shyest person you would ever want to meet. It’s hard to believe now, but shyness almost killed me.

Being a teenager was the worst time of my life, going to school was terrible. I didn’t hate the learning, but I couldn’t reach out and talk to other people. I felt like a loner. When I first started school I was so shy and self-conscious till everybody thought that I was saved, sanctified and fixin’ to go to heaven. They thought I was in the Church of God in Christ because I used to wear dresses all the time. The reason I wore a dress was that my momma couldn’t afford to buy me the clothes the other kids wore. But she was a seamstress, a damn good seamstress, so she would make me dresses.

Some of my negative feeling, some of what put me into shyness, came from knowing that I didn’t have some things that other kids had. I didn’t respond much in school. It was like sitting back, sort of in a shell.

A Struggle of the Mind

I was in that shell ’till 1983, when I started working at Delta Pride and met Mary Young. I met Mary when we were working together on the skinning machine. We could talk while we worked if the supervisor wasn’t right on us. One supervisor didn’t care if we talked, as long as we got the production out. Mary talked to me: “Girl . . .” She’d talk and talk, and I’d say, “uh hah, yeah.” Mary was real wild, and over time she began to break me out of my shyness.

Two years later, when we started the drive for union recognition at Delta, the union reps came in. One of them, a guy named Bobby Moses, would talk to us, and he’d ask Mary, “Is Sarah for the union?” And she’d tell him, “Yeah, she’s for the union; Sarah’s just shy.” When we’d sit around with all the reps, talking, I’d never contribute anything.

One day Bobby pulled Mary and me off to the side and he told me, “You’re part of this committee. You and Mary are the leaders of this pack. And you’re going to have to voice your opinion.” I saw then that to make a change at Delta, I had no choice but to change myself. It may seem strange to people, but the truth is that organizing Delta was what ended my shyness.

I saw that Mary and I couldn’t just stick together all the time; we had to spread out and work with different people to get the union in. I talked to the workers because I knew them. I had worked with the people on the kill line, I knew them. But when the reporters came in and began digging around, trying to see what was what, I wasn’t so outspoken. Setting that shyness aside and talking to the community is what Bobby Moses wanted us to do. He wanted us to tell the community the truth about the conditions at Delta Pride, so that they would get involved, to tell the NAACP, so that they would get involved. I had to come out of that shyness to do it.

So in the end, I had to change myself, to change Delta. So many companies in the South today still practice that “plantation mentality” on workers. If you believe in the dream you can overcome this, but it takes a struggle of the mind.

Tags

Sarah White

Sarah White lives in Moorhead, Mississippi. She is currently on leave from her job as a worker at Delta Pride Catfish in Indianola, and is working as a union organizer for United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1529. Along with Margaret Hollins, another Delta Pride worker, Sarah is writing a book on their decade-long organizing struggles in the catfish industry. (1997)