This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

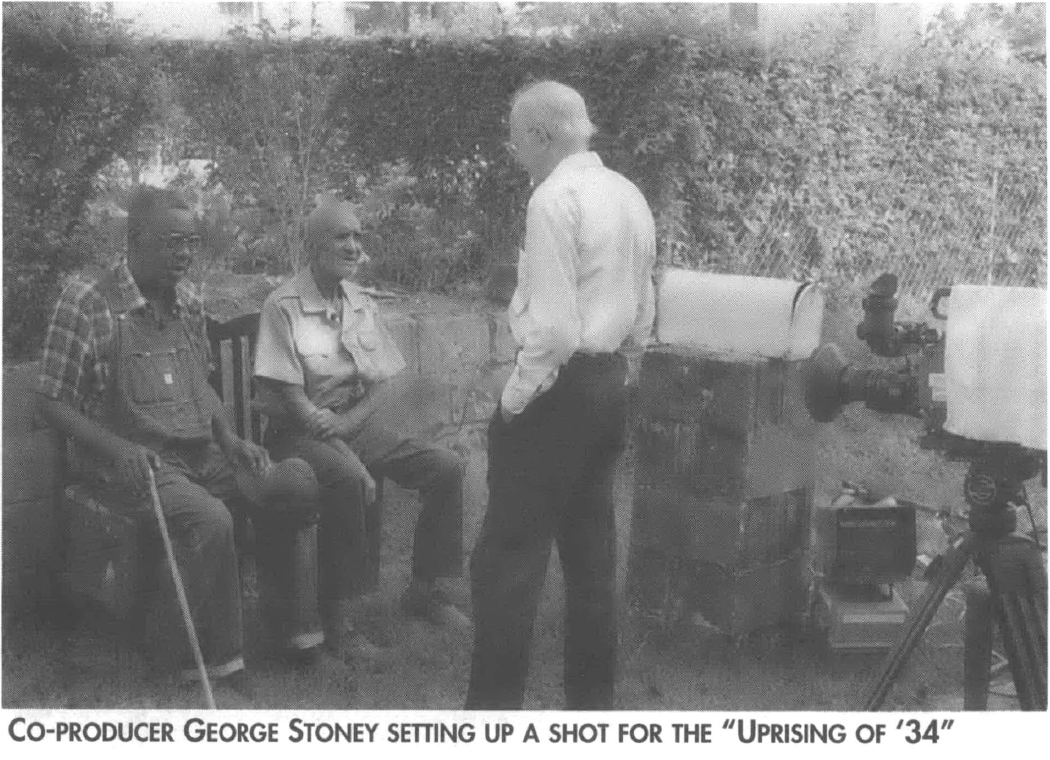

“The Uprising of ’34,” a documentary film released in 1995, tells the story of the General Textile Strike of 1934, which involved hundreds of thousands of workers, mainly in the South. The film combines oral history interviews with former workers and managers, newsreel and other film footage from the period, still photographs, and letters from textile workers to President Roosevelt and administration officials.

We never envisioned “Uprising” as merely a movie, to be seen passively. From the beginning, we were most concerned with what occurred “after the lights came up,” seeing the film as a vehicle to foster a critical dialogue about history and memory, class and power. Accordingly, we have adopted a grassroots approach to distribution and outreach, working closely with community groups, labor unions and schools.

When the lights come up at screenings in the southern cotton mill communities and cities where the strike took place, the first responses are consistently the same. “Why didn’t I know about the strike?” “Why didn’t my grandma tell me about this?” “I’m a high school teacher, and I didn’t know.” “How do we get a film and the stories of working people into the schools?”

Underlying all of these concerns was a larger question that rose to the surface like cream in a bottle of milk: “Whose responsibility is it to impart labor history to the next generation?” The answer was clear: the responsibility resides with a community and cannot solely fall to a teacher in a classroom.

When showing the film in a classroom, by way of introduction I explain how we will work with “The Uprising of ’34”: “The ground rules for viewing the film are: if you laugh, cry, squirm or yell at the screen, then I will stop the VCR and ask, “Why? What does that person or statement make feel or think about?”

An exchange that took place in an 11th grade history class in Charlotte has informed every classroom and workshop experience since. After showing the opening three minutes of the film (montage of interior mill footage and voiceover bites about life and work in the mills from owner, management, workers, young descendants), I stopped the tape and asked, “What is different about this?” expecting a talk about the novelty of not having a narrator.

One girl offered, “Well, they are real country.”

“Well, we’re real country,” responded another.

“No, they are really country, no one in my family talks like that.”

“Well, my whole family talks like that, so I guess we are real country.”

A third girl broke into the discussion. “What’s different is that they don’t show rednecks on television anymore.”

I asked, “Why not?”

A boy sitting in the back of the room took his sweatshirt hood off his head and replied, “Because people think that they don’t have anything to say that is important, and besides, they weren’t the victors.”

“Well, let’s see what they have to say,” I suggested, and turned the film back on.

We viewed the next section, a four-minute montage of retired and young cotton mill workers who speak about why the history of the ’34 strike in the South is not known. I stopped the VCR again. I asked two boys (white) why they were making so much noise while the woman in the film, who was missing some front teeth, was talking.

The two boys looked at each other sheepishly and then one said between embarrassed giggles, “Because she looks like what we were saying before—redneck. You know, white trash.”

I asked him, “Well, do you remember what she said?”

They both looked taken aback when they realized they didn’t know what she had said.

A girl (African American) sitting in the very front of the class spun around in her desk and said, “That’s because you were too busy laughing at her, but what she said was very meaningful.” Verbatim, she repeated the lines: “My daddy could talk about the war and people being blown to bits but he couldn’t talk about his own neighbors being killed [in the strike]. And it’s like somebody is trying to hide a dirty secret about their family, like they’re ashamed of what happened to their families. They ought to be proud of ’em, they stood up when other people wouldn’t.”

I asked, “What does her statement and our discussion make you think about?”

One boy offered, “Well, she makes up in wit what she lacks in appearance.”

“Well,” I asked, “what does that say about history?”

The same boy in the back of the room (African American) who had spoken earlier, pulled the sweatshirt hood off his head and said, “It means that we only know the history of people that look good or are rich. And they don’t ask regular people about their history, because we don’t even think they have one.”

At this point, we had seen just six minutes of the film.

As a way to extend this to the “regular” people who make and keep our local history, we encourage teachers, with other community leaders or organizations, to coordinate a community screening of “The Uprising of ’34.” Bring together parents or family members, working people, trade unionists, clergy, librarians, archivists, local historians, and retirees to view the film and talk. Interrupt the screening for discussions. Identify “hidden” labor history in your family or community, past or present—something no one talks about, but everybody knows about, something you know as a one-liner or myth, something misunderstood, something that is off-limits.

The point of this is for people to see themselves in an industrial and historical context and to make real connections between their families, home community and the story of the southern textile communities that are featured in “The Uprising of ’34.”

Tags

Judith Helfand

Judith Helfand is an independent film and video maker based in New York whose credits include “The Uprising of ’34” and the newly released documentary “A Healthy Baby Girl.” This piece was excerpted with permission from the Organization of American Historians Magazine of History, Spring 1997. (1997)