Deviled Eggs

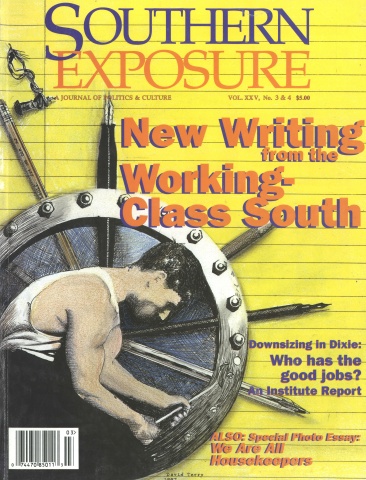

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

Addie Bea gathered up her Lone Star quilt, her two favorite dolls—Polly and Anne, and a tiny blue pot from a doll tea set. She placed them carefully in the bottom of the white cotton sack she dragged her most mornings.

“Addie Bea,” her daddy hollered in to her. “You gonna make your mama late to work.”

She kissed her teddy bear, Bo, on the nose.

“Sorry Bo, you’ll have to go tomorrow,” she whispered in his ear.

Emmitt T. and Oline stood outside the back door waiting for their daughter. Emmitt T. paced back and forth across the short length of the rock steps while he spun the skeleton key, which dangled from a string, around his forefinger. Oline held the screen door open, tapping her foot anxiously on the packed dirt that made a half circle around their back door.

“Lord, here she comes with all that stuff again,” Oline said, shaking her head. “This child gonna make Miss Lula mad for sure. You know she don’t take much a likin to kids anyhow.”

“Girl, put all that ole stuff up under the kitchen table and bring your self on out this house,” Emmitt T. said. “Now,” he said when she hesitated.

Big, sad tears rolled down Addie Bea’s cheeks as she squeezed into the front seat of the truck beside her parents.

“Mama, I don’t want go to Miss Lula’s,” she tries to explain through wet eyes. “I don’t like her, looking like an old haint. Biscuit dough, Elmer’s glue looking . . .”

“Well, I don’t care if you like her or not,” Oline fired back.

“. . . like an old haint,” Addie Bea mumbled under her breath.

“And don’t you go calling your elders names—be they black, white or green,” Oline said.

“You going and I don’t want to hear no more ‘bout it. And don’t bother that woman for nothing today. You best behave yourself. You hear me?”

“Yes ma’am.”

Addie Bea continued to cry and wished she could work the farm with Emmitt T. today. And her mama always did say that she was her daddy made over. So why couldn’t she go with him?

She pursed her lips to ask, but when she looked up at her mama’s face she could see there weren’t no use in wasting breath asking.

Addie Bea’s summers were most always spent playing in well-kept yards and roaming through other folks’ houses while her mama worked for first one, then another white family. If they had kids, she didn’t roam though. Sometimes the kids made fun of her clothes or called her names.

Like Red Pete and his brother Re-Pete, of course that wasn’t their real names, except the Pete part, but everybody called them that ’cause they was brothers with the same name. They called her names all the time, like pickanny and jigaboo, but after Addie Bea beaned their heads with a rock or two, they seemed to get along all right. They had even managed to play ball together once they saw how good she could throw.

When the people her mama worked for didn’t have kids or it was an old person whose kids were grown up and moved out, Addie Bea would bring her toys and pretend like she, Oline and Emmitt T. lived in the houses. They were always nicer than her own house, with big white columns on the outside and fluffy carpet that feet could get lost down in on the inside.

But Addie Bea did not like Miss Lula. Her face wasn’t pretty and her ways weren’t either. She was the ugliest woman that Addie Bea had ever seen. The wrinkles in her face were cut deep like cracks in a dry creek bed. And always in the front of Addie Bea’s mind was the day that Miss Lula had called her a “nigra girl” and Oline had just kept on dusting and humming “Amazing Grace” real low. That night she had asked “why” but Oline and Emmitt T., they just looked at each other and told her that still waters run deep.

“I’m gonna go get James today,” Emmitt T. said, raising his voice a little above the rattling of the pickup truck. “I’m gonna try to get that field plowed, graded and sowed ‘fore the rain hits. I smell it comin but the moon is right for plantin today.”

“Yeah, look like rain’ll be here ’fore long—’round ’bout suppertime,” Oline answered, looking out the front truck window toward the sky.

Addie Bea looked up at the sky, too, but she couldn’t figure out what her folks were talking about.

“Looks blue to me,” she said.

“Looks sometimes deceivin’, girl. Things ain’t always what they seemin’ to be. Sometimes folks got to see thangs other ways ’cept with they eyes.” Emmitt T. said, and winked and nodded toward Oline.

They followed the path of the gravel road till it ended, and Emmitt T. turned the truck onto pavement. White houses peered above green hills and continued to get bigger as they got closer to town. Emmitt T. pulled into the white gravel driveway of Miss Lula’s house, got out and came around and opened the passenger door for Addie Bea and Oline.

“See y’all this evenin,” he said.

“Bye Emmitt,” Oline said, and kissed her husband on the crest of his bald head.

“Bye Daddy,” said Addie Bea in her softest ‘Daddy’s little girl’ voice.

Emmitt T. kissed her pouting lips.

“Bye, baby girl,” he said.

He shut the door, ran back around to the driver’s side, jumped in and sped back toward the farm. “My Daddy ain’t never been one to be too long in town,” Addie Bea thought to herself. “He’s sure nuff in a hurry to get on back to what’s his.” At least that’s what her mama had said from time to time as they stood on mornings like these watching him speed off into the distance.

Oline’s shoe heels clicked against the concrete as she walked up the sidewalk to the entrance of Miss Lula’s house. Addie Bea stalled in the driveway as long as she could, kicking white gravel dust on her brown shoes and watching the path of her daddy’s truck long after it was clean out of site.

“Girl, come on here,” Oline called. “And stick your lip back in ‘fore I pull it off.”

Miss Lula opened the door and poked her head out. Small bits of color, yellow streaks in her white hair and her fading blue eyes, gave her face some life. Other than that she was equally as white from the top of her head to her neck, where the pink of her dress began.

“Oh, it’s you, Oline,” she said, opening the door for both of them but ignoring Addie Bea. “I didn’t know who this colored woman was on my step.”

“Momin’ Miss Lula,” Oline said, letting the foolish comment slip on elsewhere. Addie Bea walked into the screened porch, avoiding Miss Lula’s face. She chose being ignored over being patted on the head, which Miss Lula was inclined to do at times.

It always made Addie Bea’s insides churn to see her mother running around saying ‘yes ma’am’ and ‘no ma’am’ to white folks that weren’t any more grown up than she was. The inside out feeling stayed with her all day, and resent settled like sediment in the pit of her belly.

“Oline, I don’t need a whole lot done today,” Miss Lula said, sashaying away, her back facing Oline. “If you could just touch up each room, clear out the pantry and freshen up the ice box that’ll be fine. And I’m taking company this evenin’. I’ll cook and get the linen off the line, if you’ll just make sure they are washed. You can save your ironing for Wednesday.”

“Yes ma’am,” Oline said. “I don’t see much problem ma’am, but it’s gonna rain this evenin’ and . . .”

“Don’t be daft girl,” Miss Lula laughed, turning facing Oline. “Look, not a cloud in the sky,” she said, pointing toward the window. “You coloreds with your hoo-doo and what have you—thinkin’ you can predict the weather. “ Miss Lula turned her back and laughed real snooty—like all the way into the other room.

Chills ran up and down Addie Bea’s spine like she had just sucked the juice out of a lemon.

“Go on out in the backyard,” Oline whispered to Addie Bea. “Just play out there for a little while. I’ll call you when it’s time for lunch. I got a couple of sandwiches wrapped in wax paper down in my pocketbook.”

Oline kissed Addie Bea on her top plait and patted her lovingly on the backside as she skipped off to play. “Stay in line, child,” Oline whispered, as much to herself as to her baby girl.

Addie Bea stood in the middle of the backyard looking around for something she could do without her dolls and her tea pot. Between the rose bush and the walnut tree looked perfect for the tea party she had planned, but she’d have to make do without them.

Addie Bea laid on her back in the grass looking up in the clear blue sky. Blades of grass pierced the backs of her legs and pierced through her cotton jumper. She stood up.

“Oline, I don’t need a whole lot done today. I’m having a tea party,” Addie Bea said, to the emptiness of the yard. She put one hand on her hip and jumped to the other side. “Look, you ole pasty-face heifer, I ain’t gonna work my fingers to the bone foolin’ with your ole house,” her imitation Oline voice fussed back. “‘Sides ain’t you got the blasted sense to see that it’s gonna rain.”

“Well, I’m gonna fire you. I don’t like your girl anyway.”

“Well fine. Then I quit.”

Addie Bea stormed across the yard walking her mother’s walk.

She soon lost track of time. As the morning moved on, she claimed every corner of the yard for her own.

She played a concert to the trees at the edge of the woods that surrounded the far ends of Miss Lula’s yard. She sang and played her own mouth horn formed by a blade of grass placed between her thumbs.

Down the hill was her school; First Smell Good Baptist Church was over by the fence row; and her fishing hole was the concrete slab over the cistern.

“Addie Bea,” Oline yelled out the back door of the porch. “Come on in here and get your sandwich out my pocketbook. I’m still workin’ and can’t take no break right now.”

Addie Bea followed her mother into Miss Lula’s kitchen.

“The child can eat with me,” Miss Lula said, appearing from another room wiping her bony wet hands dry on the pleated front of her dress.

“No . . .” Oline starts.

“Why sure I can,” Addie Bea interrupts, thinking whatever Miss Lula is cooking has to be better than a half-a-day old sandwich all squashed in her mama’s pocketbook. “I sure am hungry.”

Oline’s eyes widened to that mama look that all little girls know and her hands flew to her hips. She was about to speak when she was interrupted again. This time by Miss Lula.

“Why Oline, ’course the child can eat with me. I’m gettin’ ready to fix myself some lunch right now. I got some leftovers. It’s no problem really. Is there a problem?”

Oline didn’t finish her sentence and Addie Bea disregarded the look in her mother’s eyes even though she knew she’d have to answer later.

Oline began cleaning out the pantry while Miss Lula prepared to cook. Addie Bea put on a real act for Miss Lula.

“Miss Lula, I like your dress,” she said.” Mama says you cook real good.”

Miss Lula began to warm up the leftovers, while Addie Bea sat on a wooden stool beside the entrance to the back porch and waited. She kicked her shoes one against the other in anticipation. She looked at first one and then the other rose-covered wall and up and down from plastered ceiling to wood floor, dodging her mother’s eyes.

Oline finished the pantry and started in on the icebox before Miss Lula finished.

Addie Bea squirmed on the stool. Her mother’s eyes were burning a hole clean through her. She turned her head toward the porch and concentrated on the smells. “Let’s see,” Addie Bea thought to herself, “roast, new potatoes, greens—no, green beans and a big dessert—apple pie—cobbler, maybe.”

“Addie Bea, come on and eat,” Miss Lula said, and picked up her plate of steak, new potatoes and string beans and sat at the far end of the lemon-oiled wooden table.

She motioned for Addie Bea to sit at the opposite end. Addie Bea walked the long length of the table toward the plate. It was covered with hard-boiled eggs from edge to edge. Addie Bea froze in her footsteps.

“Go on gal and sit down, so I can get started on my lunch. Don’t you have any manners?” Miss Lula said.

Addie Bea plopped down into the wooden chair so hard she hurt her tailbone.

She eased her teeth into the peeled shiny whiteness. Soft, gooey egg yolk spilled into her mouth.

“Eggs is good for a growin’ gal,” Miss Lula said.

“You need some salt?”

Addie Bea shook her head, no.

She edged her mouth open and cupped her hands up to her lips, but her mother raised her head up from inside the icebox and focused her most serious “mama look” right between her daughter’s eyes. Addie Bea chewed.

She winced and wiggled back and forth in her chair as she ate, occasionally looking at Miss Lula eating her steak, her wrinkled chin flopping with each bite. After forcing the last half-cooked egg down her throat and drinking two full glasses of water, she rose from her seat. Both women stopped their motions. She quickly sat back down.

“Can I be excused, please?” she pleaded.

Both heads nodded.

Addie Bea returned to Miss Lula’s backyard but it was just a yard again now. She laid on her back in the grass and let the blades prick her skin like dull needles. She watched the sky above her spinning and turning from bright blue to hazy white. She watched the sun struggle to shine through the clouds.

She just laid there watching the sky playing tag with the sun until she heard Emmitt T.’s truck pulling onto the gravel. She heard voices coming from the back porch, but she didn’t move.

“Yes. I got everything done, Miss Lula,” Oline was saying, “’cept that load of bed clothes I put out on the line this mornin’. You sure you don’t want me to go ‘round the side and get it? Rain ain’t far off.”

“There you go with that hoo-doo again. I told you there’s no chance of rain today,” Miss Lula said.

“Come on Addie Bea,” Oline said.

Addie Bea jumped to her feet and glimpsed Miss Lula placing a crisp five-dollar bill in her mother’s hand as she ran toward the truck.

“See you Wednesday,” Miss Lula said to Oline, acting like Addie Bea was never there.

Just as Oline and Addie Bea settled in the truck and Emmitt T. shifted into reverse, a clap of thunder broke loose and hard raindrops started beating down on the truck.

“Got it plowed just in time, baby,” Emmitt T. said, smiling at Oline, his shirt still wet with the day’s sweat. “Good,” Oline said, as she kissed his sweaty face and patted her left hand on his right knee. “Good.”

“What we gonna have for supper tonight, sweet woman? I sure done worked up an appetite today,” Emmitt T. said, reaching over to squeeze Oline on the portion of her big bronze leg that peeked from beneath her skirt.

“Don’t know,” Oline said, staring out the window smiling. “But whatever we having, a big mess of deviled eggs sure sounds good to go with it.”

“Don’t you think so Addie Bea?” she said looking over at her daughter.

Addie Bea held her belly, pressed her forehead against the coolness of the rain-specked window and prayed to live to see Bo, Polly and Anne at the next tea party.

Tags

Crystal Wilkinson

Crystal Wilkinson is a short story writer and poet. She grew up in rural Indian Creek, Kentucky, and currently teaches creative writing at the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington. She is a founding member of the Affrilachian Poets and the Bluegrass Black Arts Consortium.