America's Blackest Child

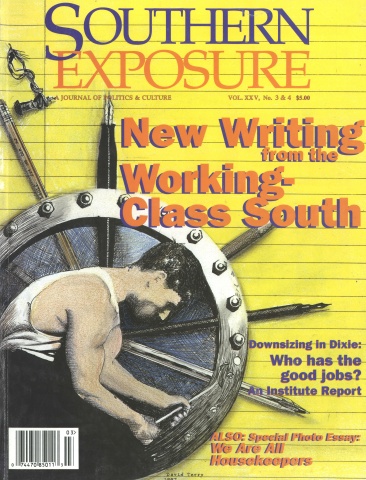

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 3/4, "New Writing from the Working-Class South." Find more from that issue here.

“A.B! Is that you? What the hell are you doing here?” I blurted out. “You supposed to be in Chicago.” It was a lame cover, but I was shocked. Not just because he was 60 pounds thinner and looked like death sitting on a soda cracker. He was the last person I expected to see in the Bay Area as a “resident” of the Evergreen Hospice Care Center, where I was working as a volunteer.

I’d heard about the places they had for people to go to die, but it was my first time spending time in one. The majority of the people there were dying of the illness that they later came to call Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, AIDS.

“Always think positively,” they would tell us in the volunteer training sessions. “They know they’re dying. They wouldn’t be here if they weren’t dying. They don’t need you to tell them that. Emphasize the living, the quality of life.”

A.B. aimed a gaunt, hollow-eyed stare at me over the copy of Fortune magazine. Even that thin magazine seemed too heavy for his fragile fingers. His eyes rolled toward the clock and back before he said, “I don’t know who you are, and you obviously don’t know me. If you don’t mind, I’m very busy.”

There was no doubt it was him but I couldn’t tell whether he was ashamed of being seen in this condition or if he really couldn’t recognize me. At the time I didn’t look too good myself. I’d dropped out of college in ’66 aiming to work long enough to pay my way back into Howard University so I could finish my senior year, but my number came up in the draft lottery. In little or no time, I was on my way to Vietnam.

My discharge papers say I served two tours of duty during the worst part of the war. I still have nightmares about it, but all I can say for sure is that I walked right up to the gates of hell and came back with no physical injury that left a scar. I was discharged with a bunch of medals that I got only because I was too scared or too stubborn to die. I sure didn’t believe what they sent us there to fight for. Hell, I couldn’t even figure out what they thought it was.

Most of what happened in ’Nam is still a blur of dope, alcohol, helpless whores and languages that I no longer understand. I hid out in Bangkok because I knew that I couldn’t get the dope I needed by that time at home in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. I woke up one morning two years later in San Francisco’s Chinatown feeling like I must have walked all the way from Bangkok. It was another year and a half before I could stay sober long enough to keep a job busting dishes.

I had started going to Evergreen because Joe Walker was there. I could remember that he’d been my best buddy when I got to Tan San Hut. Joe and I were the only college men in our unit. In fact, Joe had gone into service on a ROTC commission but had gotten himself busted back to buck sergeant because of repeated drug charges. He’d hoped that his record would keep him from being assigned to combat duty in the Boonies. It didn’t.

Like me, Joe had survived but came back home a junkie. His family had a little money so they’d “put him away” because they didn’t want anyone to know about his condition. I started visiting him because he was my buddy and because I hoped he might hep me remember what had happened to me. It was already too late for Joe by the time I found him. I’d sit and talk to him, but I couldn’t make sense of what he was saying. I wasn’t there when he died.

Unlike Joe, A.B.’s body was running down but his mind was still strong. After I kept on coming back and talking to him he must have decided that I was so crazy myself that it didn’t matter whether he talked to me or not. At least I wouldn’t be laying some heavy trip on him. Hell, I couldn’t tell my ass from a hole in the ground, who was I to judge? You can get really close to somebody in a situation like that.

A.B.’s real name was Martin Cohen. He’d been at Howard at the same time I was there. He was from this little town outside of D.C. Everybody used to tease him about being Jewish because of his name but there was no way that you could mistake him for being Jewish once you saw him. His other pet name was “ABC,” “America’s Blackest Child!” Martin “A.B.” Cohen.

He didn’t mind it when you called him “ A.B.,” but he’d get fighting mad when you called him “The Black Jew” or anything like that. It seemed kind of crazy to me, because all the while we were in school he went out of his way to hook up with Jewish women. And they loved A.B. too. He was coal black and just as pretty as he could be.

It was embarrassing to go out with him when he was with one of them because they’d make such a big thing about his skin and his hair. They’d be touching and teasing each other no matter where they’d be, and that stuff can be dangerous in some places now!

A.B. was all about money. Far as that’s concerned, he’d done really well with his life. He was one of a very few to have a seat on the Chicago Board of Trade at the time. He always had money when we were in school. I couldn’t see where he should be making that much money so I figured it was cause he was so tight. He’d made both of his two brothers make business plans and report to him on their progress in order to get any money from him. On the other hand, the first thing he did when he could afford it, was to buy a house for his mother and set her up with a trust fund “because” he said, “she’d already worked hard enough for two or three lifetimes.”

His mother had raised the family without the help of a man, no more than it took for them to be conceived. She’d done it by doing housework for the white folks. The way he explained it, she was sort of like an independent contractor. She would contract for particular things, like doing the floors and windows in a house once every two weeks or cooking the weekend meals, or doing the laundry and ironing once a week, stuff like that. She had it figured that she could make more money and keep control over her own time that way. She got to the point where she worked almost exclusively for Jewish families because she found that she could get fifty cents to a dollar an hour more from the Jews.

When A.B. was growing up, her main contract was with this family that had this really beautiful daughter named Millicent, who was about A.B.’s age. He said that she was really beautiful. From the very first time he met her, he thought Millicent was the object of all his erotic fantasies. She seemed so nice whenever he’d go over to wait on his mom or to help her out if she had a really tough job to do. In the early fifties, it was quite a thing for a white woman to be nice, or simply “civil” to a black person notwithstanding the fact that they were both children at the time. It was only a couple of years earlier that they had lynched Emmitt Till in Mississippi.

Where I had dropped out of college and gotten drafted, A.B. had pled family hardship and stayed in school. He got a fellowship to the University of Chicago to work on an MBA. Who should he find there but the Magnificent Millicent from his hometown. Here she was, his childhood fantasy in the flesh, as a fellow student in the same university.

He described a ravishing woman; raven black hair, translucent ivory skin, perfectly matched teeth framed by pouty strawberry-red lips that required no lipstick for their redness, piercing hazel brown eyes and a luscious sensual body, which she inhabited with a comfortable grace that made her even more appealing.

A.B. was excited about finding Millicent again but was shocked to discover that despite his deadly reputation with women, particularly Jewish women, Millicent, though friendly enough, seemed to have no particular interest in seducing him regardless of the lengths to which he went to make himself available.

What was even more shocking, however, was the fact that she didn’t remember him. One day he baited her with the disclosure that he was from her same hometown. “Oh,” she said, “I’m ashamed to admit that the only black person I knew growing up was this wonderful human being named Gertie, who was . . . well, kind of a maid for us.”

“Gertie?”

“She was a really wonderful person. In some ways she did more for me than my mother did . . . about learning how to be a woman, a complete human being, you know.”

‘“Aunt Gertie’, huh?”

“Yes! That’s exactly what we used to call her! How did you know? Is that . . . like a common term of endearment among your people?”

“A ‘common term of endearment?’”

“You know . . .”

“Among some people, yes. I suppose you could say so.”

A.B. waited in vain for Millicent to make the connection. She never did. Even after he went on a campaign to win her affection and to make her one of his regular lovers, she never did make the connection between him and his mother.

He was surprised that it was so easy to convince her to participate in group sex with other black men. A.B. said that Millicent was the one who suggested that they experiment with bondage and whipping. In time, he said, he reached the point that he enjoyed her humiliation by others more than he enjoyed sex with her himself, but she’d always insist on completing their encounters in a solo engagement with him.

Eventually, Millicent went back to D.C. to work in an investment firm later to become the CEO for her father’s bank back in Virginia. Years later, A.B. heard from his mother that the Magnificent Millicent had died at the young age of 38. She’d just wasted away, till finally she was just too weak to keep on living. The way his mother put it, “She just died for love. When people don’t have enough love in their lives they just waste away like that.”

Eight years to the day after Millicent died, A.B. had gone to the doctor to find out why he was unable to stop losing weight and was tired all the time. He’d had all kinds of tests and diagnoses; from food poisoning to gastroenteritis to chronic fatigue syndrome to things never heard of before or since. After two years, it was clear that he was only getting worse, and they were beginning to understand there was more to this Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome than met the eye.

He got to where he couldn’t keep up with the demands of his lifestyle or work anymore. He closed down his offices and checked himself into Evergreen. I asked him if he’d gotten into drugs. He shook his head. “Have you told all your sex partners you might have exposed to this condition?”

“Hell, man, you might as well start with ‘A’ in the phone book.”

A few months after I found him, A.B. died. I don’t think his brothers tried to tell his mother what was happening to him. They had a little private service at the crematorium in San Francisco. I was the only one not in his blood family there. His mother just kept saying over and over, “My baby died because of the lack of love in his life. My baby died for the lack of love.”

Tags

Junebug Jabbo Jones

Junebug Jabbo Jones sends along stories from his home in New Orleans through his good friend John O’Neal. (1994-1997)

John O'Neal

John O'Neal was a co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater for almost 20 years. He is currently touring the nation in his one-person play, Don't Start Me Talking Or I'll Tell Everything I Know: Sayings from the Life and Writings of Junebug Jabbo Jones. (1984)

John O ’Neal is co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater in New Orleans. O’Neal’s one-person play, “Don’t Start Me to Talking Or I’ll Tell Everything I Know, ” is currently touring the country. (1981)