This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 1/2, "Southern Media Monopolized." Find more from that issue here.

Senehun Ngola, Sierra Leone — Along the meandering West African coastline a black person born in the American culture can find his African roots, if he knows where to look.

Is it at the flat, sandy coast of Senegal and The Gambia, where women sew coiled baskets that resemble the golden sweetgrass baskets in South Carolina? Is it tangled in the mangroves at the Bandama River, the beginning of the old Gold Coast, a source of yams like Southern-style sweet potatoes? Is it hidden in the thick coastal forest of the Congo Basin from Zaire to northern Angola, where Bantu culture spoke words like biddy (for a small chicken) and jambalaya?

Sketchy bits of culture may have guided a few to their roots. For millions more, the nagging mystery has lingered since birth.

Mary Moran, a mother of 13 and a homemaker from Harris Neck, Georgia, has her answer now. It’s been hidden in her high-pitched voice for most of her 75 years.

While playing at a tidal creek, shelling peas at her mother’s knee or skipping under a moss-draped tree, young Mary sang a song.

Ah wakah muh monuh kambay yah lay kwambay.

Ah wakah muh monuh kambay yah lay kwan.

Hah suh wiligo seeyah yuh banga lilly.

Hah suh wiligo divellin duh kwan.

Hah suh wiligo seeyah yuh kwendieyah.

The song came from her mother, Amelia Dawley. Amelia Dawley got it from her mother, Tawba Shaw, and her grandmother, Catherine, both born in slavery. Shaw and Catherine likely got it from their mothers, whose names are lost in time.

The song had no meaning to them. It’s in a language they do not know. Still, they sang the gibberish lyrics, thinking it came from Gullah; thinking it was an old African song. They used it to entertain the children. To make them dance.

Four thousand miles away in Sierra Leone, another woman passed a song along in a similar fashion.

Mariama Suba sang to her granddaughter, Baindu. Unlike the Moran family, Suba knew the meaning of her song. In the decades before Suba died, a changing religious culture forced her culture to abandon the song. But Suba passed it on anyway, believing it to be an important part of her heritage.

For about 200 years, each song stood apart. But in 1989 they began gradually inching closer, unlocking secrets along the way.

Now Mary Moran knows the song she sings is a funeral song from the Mende people of southern Sierra Leone. Baindu Jabati knows her Mende funeral song traveled on a slave ship to America in the 1790s; twisted some by time but not much changed from the way it has been sung through the generations in Moran’s family.

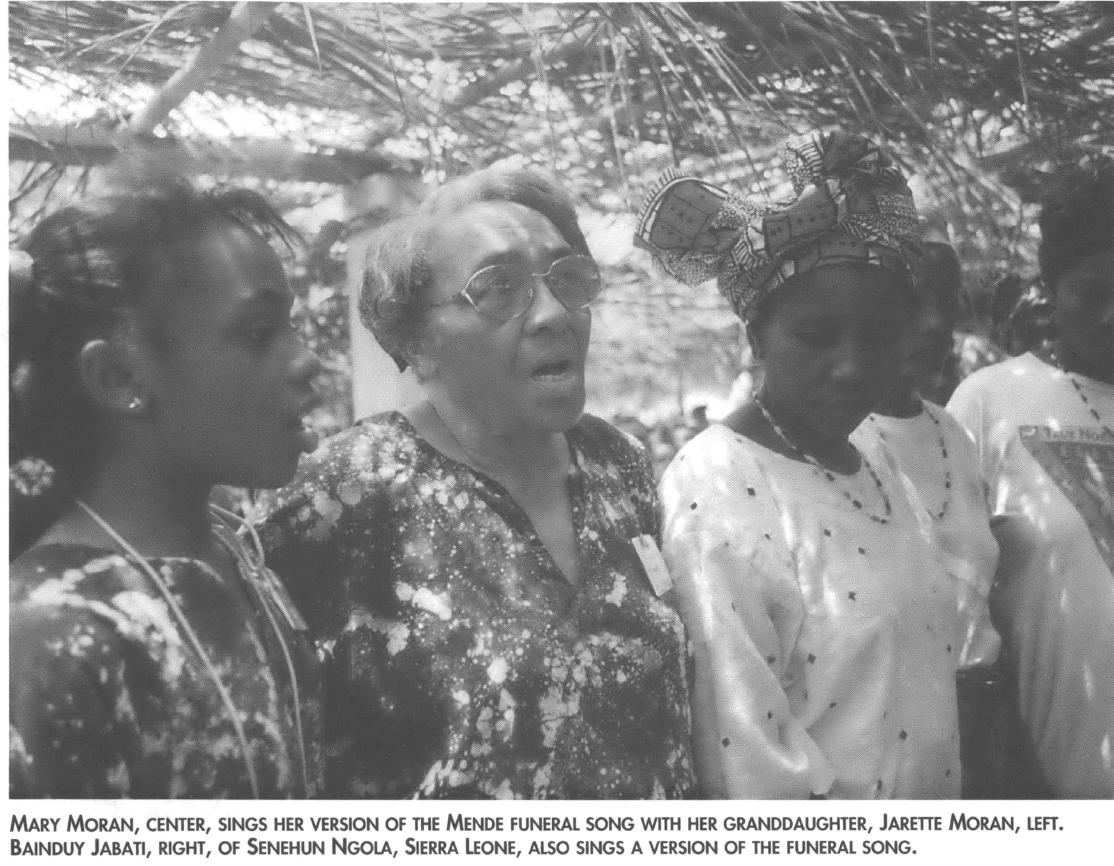

On a steamy March morning, Mary Moran of coastal Georgia met Baindu Jabati of Senehun Ngola, a rural rice-farming village hacked out of a dense tropical forest. They hugged. They cried. They exchanged their cultures and their songs.

The Sierra Leonean government invited Moran to come. After her family coaxed her out of a fear of flying to a strange, distant land, she agreed. Twelve of her relatives and the pastor of the family’s church arrived in Freetown on Feb. 26 for an 11-day visit. It was a dizzying tour during which Moran sang the five-line song for the country’s president and other leaders and was greeted on the streets of Freetown, the capital city of some 500,000 people, like a rock star.

Banners strung up around Freetown welcomed her. People stopped her on the street and in her hotel lobby to shake her hand. One woman, who appeared to be waiting on a taxi, approached the small bus carrying the Morans and waved at Mary Moran. “Welcome,” the woman shouted.

“It is amazing that this little song has brought me to Africa,” Moran said before arriving in Senehun Ngola. She fanned herself with a Freetown newspaper that carried a story about her visit. “This doesn’t seem real. It seems like I’m still in America.”

All of what the Morans had seen and done and would do seemed unimportant when compared with Senehun Ngola and Jabati. But first, they had to get there. After a nervous one-hour flight from Freetown on an old Russian-made helicopter, the Morans arrived in the village, about 80 miles from the Liberian border.

When the thick, red dust in the village’s school yard, kicked up by the whirling rotors, had settled back to earth, the craft was quickly surrounded by a crowd of singing people, like ants invading a dead bug. When Moran and her brother, the Rev. Robert Thorpe of Savannah, stepped off the helicopter, the crowd scooped them up and dropped them in separate boxed-framed hammocks that sat on the heads of men stationed at each corner.

As she swung in the hammock, Moran laughed wildly as if she were on an amusement park ride. “This is kinda funny. I’ve never in my life gotten a welcome like this.”

During the lengthy, musical welcoming procession — reserved for local chiefs and visiting VIPs — hundreds swarmed through the hot, dusty village of Senehun Ngola to greet Moran and her family. The procession stopped in the center of the village. Then all eyes were focused on the Morans, seated in the Barri Court, where village elders settle disputes.

“We are so happy to find our roots, the Mende,” Moran told the approving crowd. “We will come again.”

Joseph Opala, an American anthropologist who lives in Freetown, leads a team of two other scholars who’ve researched and translated the Mende song to English and brought Moran and Jabati together. Opala told the Mende audience their song went to America on a slave ship and today it has come back.

With those words, Jabati was overcome. She fell to her knees and buried her face in Moran’s lap. She sobbed. Later, she said, the occasion would have been better if her ancestors could have welcomed Mary Moran, too. Moran has found something most black people in America can only dream about. A real connection with her roots. When compared with another American — the late Alex Haley — who decades ago found his roots in Africa, the Moran link is stronger, historians say.

Guided by a few words in the Mandingo language, Haley’s odyssey took him to a village called Juffury in The Gambia, north of Sierra Leone. There, he claimed to have found people whose oral tradition includes the story of Kunta Kinte, who Haley said was his ancestor, being carried off on a slave ship to Virginia.

Haley had a few words. Moran has a lot more. She has a five-line song that is essentially the same as Jabati’s song, Opala said.

The song is believed to be the longest text in an African language that has been preserved in a black family in the United States, said Dr. Cynthia Schmidt, an ethnomusicologist who teaches at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Schmidt said she and Opala have looked for longer songs or stories but so far they’ve not found one.

Opala, Schmidt and Tazief Koroma, a lecturer in linguistics at Njala University College in Sierra Leone, would not have found the songs had it not been for coincidences and good fortune. The songs — on each side of the Atlantic — teetered on the edge of being lost forever.

But to understand that, go back to 1932 when a linguist met Amelia Dawley and heard her song.

First Recording

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Lorenzo Dow Turner taught summer school at black colleges in South Carolina and his native North Carolina. The peculiar speech of his students from coastal South Carolina and Georgia piqued his interest in Gullah words and culture and its African influences. Soon, Turner traveled the sea islands collecting words and stories.

In 1932, Turner, a Howard University linguist, recorded Dawley singing a song in a language he later identified as Mende. His translation of the song, along with other Gullah words, were published in his 1949 book, Africanism in the Gullah Dialect.

In 1989, Opala and Schmidt located Turner’s recording of Dawley. In Sierra Leone, they gave it to a Freetown choral group, who sang it for visitors from South Carolina and Georgia who had come on a Gullah homecoming. Mende people were surprised to learn that a song in their language had been recorded in Georgia.

Schmidt and Opala were surprised too to learn from one of the Gullah visitors, Loretta Sams of Darien, Georgia, that Amelia Dawley’s relatives were still around.

When Schmidt and Opala visited Mary Moran in 1991, to their amazement she could sing the song that her mother sang for Turner.

In Sierra Leone, Koroma, who’s from the Mende tribe, joined Schmidt on a search for the song in Sierra Leone. They went from village to village. Finally, Schmidt came upon Baindu Jabati. When Schmidt played a tape recording of the song, Jabati sang along.

Now the mission became getting Moran and Jabati together. But that would not come quickly.

In April 1992, rebels attacked villages in Sierra Leone, just across from the Liberian border. Soon the violence spread. Within a few years, Senehun Ngola was burned and flattened. Jabati, apparently the last person in the country who knew the Mende funeral song, was captured and held by rebels. She came close to being killed.

During her eight-month captivity, she was forced to collect food from the forest. None of the best food went to her. She survived on green papaya. None of the best foods went to her 6-year-old granddaughter, Sattu, either. Sattu died from starvation.

Jabati’s grandmother, Mariama Suba, and her family owned the song because it was Suba’s job in the Mende village to conduct the funerals. No one else had that right. When Suba died, the responsibility fell to Jabati. She did not pass it along.

Even though Jabati could sing the funeral song, she had no reason to perform it within its original context. The song and the funeral rite, Tenjamei, that went along with it were discouraged by Christianity and Islam, she said.

The song and the Tenjamei had became pagan rituals to be shunned, she said. The song took on a new meaning. It became a social song. But with little to cheer about in a village smashed by war, she had not sung it in years. Jabati said the song came to her lips the night she buried Sattu.

Teaching the Song

Because Mary Moran dd not know the Mende words or the song’s context, she did not teach it to her children until 1991, when Opala and Schmidt visited her and told her the song was connected to the Mende people.

Moran’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Jarette Moran, knows the song now, and they sang duets around Freetown and in Senehun Ngola.

Women in the Mende culture preside over funerals and births. The men do not sing it. The men in the Moran family, however, are learning the song now because of its new-found celebrity.

Mary Moran’s son, Wilson Moran of Harris Neck, said, “If the song hadn’t been found and revived, it would have been lost. It will be here for another 200 years.”

“This song is going to heal a lot of wounds left by slavery, and it is going to bring two cultures together. My mother is alive. She is real, and she is the other link in the chain.”

Tags

Herb Frazier

Herb Frazier is a reporter with the Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. (1995)

Herb Frazier is a reporter with The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. (1997)