Policing the Police

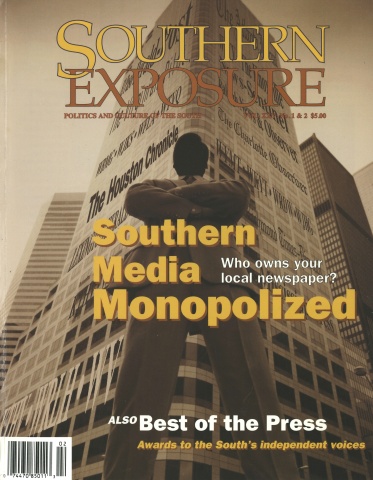

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 1/2, "Southern Media Monopolized." Find more from that issue here.

Miami New Times, Miami, Florida, Published October 24-30, 1996

Miami, Florida—Depending on one’s point of view, Alan Smith had the lousy luck to be standing ahead of Detective Frank Irvine at the Convenient Spot convenience store in North Miami on April 14, 1994. Or perhaps the misfortune was all Irvine’s. The chance encounter would cost the emotionally disturbed, 25-year-old Smith 12 days in the slammer. The North Miami police officer would see his 16-year career come to an ignominious end.

The way Irvine told it to his sergeant, his lieutenant, and his chief—all of whom eventually showed up at the scene—Irvine caught Smith trying to heist a pack of cigarettes. Smith became violent, scuffling with the detective and pulling a small pocket knife.

For his part, Smith has difficulty remembering exactly how the struggle started but he denies attacking the officer. “I kept getting beat and beat and beat,” he said in a sworn statement, explaining that all he recalled of that evening’s brawl was cowering with his arms over his face to ward off blows. Although not injured seriously enough to warrant medical care, Smith lodged a complaint against Irvine with the North Miami Police Department’s internal affairs unit.

Internal affairs investigators at police departments throughout Dade County hear such stories regularly. An individual—the subject of an arrest, the recipient of a traffic ticket—accuses a police officer of using excessive force. Investigators open a file. They take statements from the victims, the witnesses, and the officers involved, and they search for physical evidence—cuts and scrapes, ripped clothes, bruises, a photograph, sometimes even videotape.

Such inquires yield myriad outcomes. Depending on the department, either the chief, a disposition panel, or the investigators themselves review the facts gathered and then make a determination. The simplest result is also the most uncommon: they “sustain” the case, meaning that they decide the allegations are true—the officer used excessive force and is the subject of discipline.

Far more often they employ a range of categories to set aside the allegations. Although the nomenclature vary from department to department, the three main findings are cleared (or exonerated), meaning the amount of force used by the officer was appropriated; unfounded (or unsupported), meaning the allegations are false; and not sustained, meaning investigators were unable to determine precisely what happened.

This last finding might appear to be at odds with the purpose of an investigation—to weigh opposing stories and arrive at the truth—but in fact it is a routine result of internal affairs investigations. Investigators maintain that available evidence is frequently insufficient to prove or disprove one side or the other. After taking sworn statements and comparing them for inconsistencies, there is often little else they can do, they say.

Given the discrepancies between Smith’s and Irvine’s recollections of their tussle, Smith’s complaint would almost certainly have resulted in a finding of not sustained. Such an ambiguous outcome was avoided by fortuitous happenstance: the beating was captured by the store’s surveillance camera. The video shows Irvine standing behind Smith in the checkout line, puffing on a cigar.

Smith is small, lithe, and hyper, dressed in a baseball cap and jacket. He dances in place, turning again and again toward Irvine, grimacing and waving his hands in front of his face. The video is silent but the dialogue is implicit. “That cigar smells like shit, man!” Irvine, tall, bulky, and stolid, continues puffing. As Smith pays for his purchase and walks toward the door, Irvine follows him. He takes off his rings and places them in his pocket, and then grabs Smith’s jacket. Then Irvine hauls back and punches Smith, who is off-camera now. Still puffing, he punches him again. And again. Then Irvine also disappears from view. Shoppers gather, peering down an aisle, as if they were watching a fight. Irvine appears again, this time dragging Smith, whose shirt is ripped, his jacket pulled over his head in an improvised straitjacket. Irvine takes the younger man outside.

The North Miami internal affairs department sent Irvine’s case directly to the state attorney’s general office, which charged him with battery, official misconduct, and making a false statement to law enforcement officials in connection with the incident. Last week he pleaded guilty to battery and making a false report and was sentenced to one year’s probation. He also resigned from the North Miami police department.

The Dade state attorney’s office has prosecuted only about a dozen police officers for excessive use of force during the last five years. The numbers might seem low, considering that each of Dade’s 28 separate police departments regularly refers complaints involving possible criminal conduct to prosecutors before they close their internal affairs investigations. But Joe Centorino, chief of the state attorney’s public corruption division, says, “There are a lot of these cases that can’t be prosecuted. There is often a dearth of evidence, and the witness and victims often aren’t particularly credible.”

Over the past several years, numerous Dade County residents have contacted New Times with anecdotal accounts of mistreatment at the hands of police officers. Only a fraction of those have resulted in published articles. But in an effort to quantify the problem and to evaluate police response to accusations of abusive treatment (also referred to as excessive use of force), New Times examined internal affairs records for seven Dade police departments dating back to 1991. Out of a total 795 complaints, only 1.6 percent were sustained. (The seven departments were Metro-Dade, Miami, Miami Beach, Hialeah, Coral Gables, North Miami, and Homestead—which employ 65 percent of all sworn officers in Dade County.)

The significance of Dade’s 1.6 percent figure is a matter of some debate. James Green, the legal-panel chair of the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, says the numbers support the ACLU’s belief that channels for dealing with allegations of police misconduct are inadequate.

But Sam Walker, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and an expert in civilian review of police, says drawing appropriate conclusions is not so easy. “The official numbers on sustained complaints are tricky,” Walker observed. “In some cases they mean the opposite of what they appear to mean.” Rather than indicating a problem with the way excessive-force complaints are investigated in Dade County, the low-sustained figure may simply mean the departments have been successful in persuading the public to utilize the process, thus generating a large number of frivolous or hard-to-prove complaints.

Nevertheless, Walker concedes, Dade’s numbers appear to be unusually low. He cites a 1993 study by the Police Foundation, a nonprofit, Washington, D.C.-based think tank, which found that municipal police departments nationwide sustained 10.4 percent of all excessive-force complaints they receive.

Sheldon Greenberg, director of Johns Hopkins University’s Police Executive Leadership Program and a member of the Justice Department’s working group on police integrity, agrees that statistics alone don’t accurately reflect how a department is handling complaints.

More important, he asserts, are the quality of the investigations, the extent to which the public is encouraged to make complaints, the ease with which they can make complaints, whether the complaints are taken seriously by internal affairs units, and whether a department has a method for tracking repeated complaints against a particular officer regardless of whether they are sustained.

In order to address those factors, New Times scrutinized more than 175 individual internal affairs investigations from 1991 to 1996. Overall the investigations were professionally conducted, though some departments—Metro-Dade in particular—were more thorough than others in tracking down witnesses and documenting each step of the process. Metro-Dade routinely canvassed neighborhoods searching for witnesses, going so far as to dispatch investigators to a neighborhood or an intersection in the middle of the night to hunt for onlookers who might frequent the area at that time.

Since the early 1980’s, Metro-Dade has housed its internal affairs unit, known as the Professional Compliance Bureau, in a separate building several miles from police headquarters. Metro Deputy Director G.T. Arnold says the department wants to make it easy for an officer to provide information about a colleague whose behavior is out of line without that officer being blackballed as a snitch. In addition, Metro-Dade believes that separate locations help to alleviate civilian complainants’ feelings of intimidation. Metro-Dade, Miami and Miami Beach all have some type of early warning system in place that counts the number of complaints filed against a particular officer. At Metro-Dade two internal affairs complaints or three involving force (but not necessarily leading to a complaint) over a three-month period prompt a computer-generated report advising a supervisor to review an officer’s behavior.

Experts at improving the relationship between police departments and the communities they serve recommend such measures as a way of improving the effectiveness of internal affairs sections and ensuring the integrity of the internal affairs process. But despite such efforts, the level of skepticism among many members of the public remains high. The reason is simple: even the most meticulous investigators rarely sustain complaints.

By way of examination, police chiefs cite several phenomena. First, they say, so-called victims often don’t understand the difference between excessive force and necessary force. Police officers are permitted, and sometimes required, to use force to make an arrest, they emphasize. Moreover, in order to boost public confidence in internal affairs, the chiefs say their departments do not screen the complaints they receive, a portion of which are frivolous or impossible to prove. According to internal affairs records, cases sometimes dead-end because the alleged victim disappears or stops cooperating. Additionally, many alleged incidents of excessive force are one-on-one encounters, and without supporting evidence or impartial witnesses it often legally impossible to sustain them.

Indeed, excessive-force complaints resulting from one-on-one encounters were infrequently sustained during the five-year period examined for this article. Even the appearance of an additional witness didn’t necessarily clarify the nature or extent of the conflict.

Around the nation, communities are developing new methods to improve the credibility of the internal affairs process. Los Angeles County; Portland, Oregon; and San Jose, California, for example, have employed independent internal affairs “auditors.” Says the University of Nebraska’s Sam Walker: “Auditors can sit in on interviews with the witness, or they can review the transcripts of the tapes and look for bias, a failure to follow-up with an obvious question. If the investigators are asking leading questions to officers, they can catch that.”

Since 1980 Dade County has had an independent review panel that investigates complaints against county employees, including police officers. The panel functions similarly to an independent auditor in that it can review the work of police investigators and issue its own findings, which in some cases are at odds with those reached by the department. Its mandate, however, is to investigate complaints, not to monitor internal affairs departments.

“One thing that police administrators could do [to boost the public confidence] is to have as open a civilian-review process as possible,” advises Wes Pomeroy, who founded the Dade review panel.

Miami Police Chief Donald Warshaw says he welcomes public scrutiny if it will improve his department’s relationship with the people he serves:” We really want the community to feel they can come in here and make a complaint against an officer and not have any kind of retribution and get a fair and accurate investigation.”

Other Winners (Investigative Reporting, non-daily commercial): Second Prize—tie—Edward Erickson Jr. of The Orlando Weekly for his investigation of a secret meeting of the nation’s leading right-wing conservatives in Florida and Bob Burtman of the Houston Post for investigating the petrochemical industry and its effect on communities and workers in Houston. Third Prize—Kevin Hogencamp of the Folio Weekly for “A Hard Day’s Night,” which explored the world of the men and women who work as day laborers in Jacksonville, Florida.