A League of Their Own: A Professor Confronts the Southern League

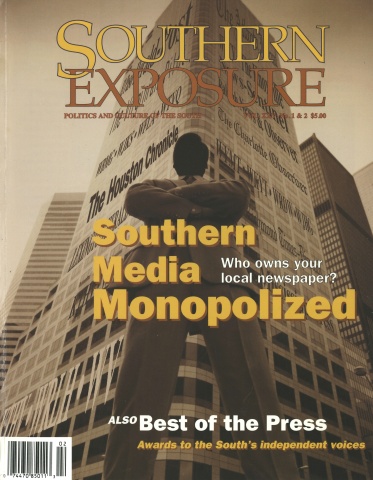

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 1/2, "Southern Media Monopolized." Find more from that issue here.

I am a traitor to my heritage. I am a traitor to my race. I am committing “cultural genocide” against my own kind: white, Christian, Anglo-Celtic Southerners whose ancestors fought against the Army of Northern Aggression. I am, according to the Southern League—a rapidly-growing secessionist group of mostly middle-class, often academic, certainly angry, white men—the Enemy.

Me, Bill Clinton, “the nest of pernicious neo-conservatives in Manhattan,” Ken Burns, the U.S. Civil War Center, Governor David Beasley of South Carolina, Wall Street, the Ivy League, Jews, feminists, the NAACP and especially the “Yankee professors” who have infiltrated Southern universities. We’re all at it, practicing what the League calls “cultural ethnic cleansing” on the tattered but valiant remnants of the Old South.

I teach at the University of Alabama. One day in late 1995 the president of the student branch of the Southern League, a big, dark-haired, fifth-year senior named George Findlay, walks into my office and tells me he is investigating a “complaint” that I am disrespectful about the South in my classes. Stalking back and forth in front of my desk, he says the Southern League has ways of dealing with liberals like me. He says they will be watching me, “monitoring” my courses; he promises the Southern League will be vigilant. Findlay leans forward, looking at me: “I heard you tell your classes that slavery was a sin.” He jabs a finger at my Bible: “Show me in there where it says slavery is a sin!”

Images of a career dogged by the Dixie version of Accuracy in Academia are jump-cut in my head with half-remembered newspaper stories of disturbed students shooting professors in their offices. The one thing I know about the student Southern League is that they raffled off a rifle earlier in the semester. Of course they all have guns. It is Friday afternoon, not many people around. I make sure I can reach the phone. Suddenly George Findlay sits down in my spare chair, heavy as a bag of sand, staring at the bits of paper pushpinned to my office walls. He demands to know where I’m from and where I went to school. I tell him I’m a sixth generation north Floridian with two degrees from Florida State University and a doctorate from Oxford University.

Sitting up just as straight as his mama undoubtedly told him to, Findlay can’t decide between menace and icy politeness. He says white Southerners are tired of being “harassed” and “insulted” over their Confederate heritage. He has heard that I ask my (mostly white) classes what it must feel like to be a black student on this Tara-fied campus (even the Business School parking garage has white columns) where the plantation house is reiterated over and over again. “Don’t, Dr. Roberts,” says George Findlay, “don’t let it get back to me ever again that you have bad-mouthed our Southern heritage.”

Findlay is breathing as if the air in my office hurts him. I realize that he is just a kid, after all. Somehow he and the couple of dozen other Alabama fraternity boys in the student Southern League (they refer to themselves as “young high-minded gentlemen” in their charter documents and list “chivalry” as the chief membership requirement) have convinced themselves they are oppressed, victimized by an administration they see as deferential to minorities and a faculty they see as tenured radicals out to smear the honor of the Old South.

They don’t understand what happened to the University of Alabama their parents enjoyed, the football-obsessed party school where the children of the Deep South elite went to join the right clubs, drink, get into law school, get engaged, and meet future political backers, minds unchallenged by anything outside of ancien regime decorum. At that Alabama, the only blacks around were serving chicken Marengo and sweet tea at the Delta Kappa Epsilon house.

But behind George Findlay and the “chivalric” students who booed Alabama’s black homecoming queen lies the grown-up Southern League, the collection of 4000 or so members—many of them academics—in chapters all over the country but headquartered here in Tuscaloosa.

The League is the brainchild of Dr. Michael Hill and several other white, pro-Confederate scholars, founded in1994. Its mission, they say, is to “affirm the proud legacy of our Anglo-Celtic civilisation (sic) with no apology.” I am just about to ask George Findlay about them when he gets up and leaves, as stiff and as dangerous as he can be and still remain—as he calls himself—a gentleman. A Southern gentleman.

Rising Again

The Southern League goes way beyond bumper stickers with Yosemite Sam in Confederate gray howling “Surrender, hell!” or re-enactments Robert E. Lee of First Manassas where the guys alternate being Yanks and Rebs from year to year in the sure and certain knowledge of barbecue later on. The Southern League isn’t into dress-up: they want the South to leave the Union. Again. Their name sounds like a weekend baseball outfit but actually comes from two of their philosophical inspirations: the League of United Southerners, an antebellum group organized in 1858 by two pro-slavery thinkers, the Alabamian William Lowndes Yancey (a secessionist before secessionism was cool—he wanted out of the Union as early as 1851), and the Virginian Edmund Ruffin who, according to legend, fired the first shot at Fort Sumter in 1861. Ruffin had a blow-hard, die-harder allegiance to a South made free from democracy. After the surrender at Appomattox, he scribbled a note declaring “unmitigated hatred . . . to the malignant and vile Yankee race” then blew his brains out.

The other source is modern and European: the Northern League of Italy, the separatist party advocating an independent “Republic of Padania” from Turin to Venice. The Northern League did well in the spring Italian elections, no doubt bolstering the Southern League’s ambitions for some day fielding actual candidates in American elections.

The League’s “New Dixie Manifesto” paraphrases Metternich: “America is only a geographical expression.” They want Confederate battle flags flying from statehouse domes. They want Robert E. Lee honored with a federal holiday—just like Martin Luther King, Jr. They want to reassert what Dr. Michael Hill, national president of the Southern League, calls “the natural social order of the South.”

And they’re coming to your town. In October 1995 the League had only 10 state chapters: Now they have more than 30, from the Old Confederacy to Arizona, Illinois and Oregon. There are city chapters and university chapters. There’s a tax-exempt educational organization and plans to house it, according to the League’s newsletter, in “an antebellum Greek Revival plantation house” in South Carolina. There’s the web page(http://www.dixienet.org), e-mail (theRebmaster at FREECSA@aol.com), an electronic shopping service, booklists, national conventions, and PlantationBalls. Tenured professors at the University of Alabama, the University of South Carolina, the University of Georgia and Texas Christian write position papers for the League and serve on its national board of directors. The League has occasioned articles in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Village Voice, protests in USA Today, an exchange between slavery historian David Brion Davis and Marxist-turned-Southern-apologist Eugene Genovese in The New York Review of Books, and an admiring column by George Will. All this attention is paying off in membership numbers: “To use a Southernism,” says Michael Hill, “we’ve grown like kudzu in the last year and half.”

Michael Hill and I are having lunch, though he calls it “dinner,” the old Southern word for the midday meal. (In a recent issue of Southern Patriot, the League newsletter, James Kibler, an English professor at the University of Georgia, urges Southerners to go back to their grandparents’ language and re-adopt British orthography, Webster’s Dictionary being an instrument of Northern imperialism).

We are at the 15th Street Diner in Tuscaloosa, a white soul food place with a bottomless glass of iced tea (if you don’t want it sweet, you’d better tell the waitress fast). Michael Hill is scrupulously polite, courtly even, sporting the sort of beard Confederate generals used to wear. Over chicken gumbo, field peas, and cornbread, he tells me George Findlay is no longer president of the student Southern League—he’s dropped out of school. The former student president is called Nathan Bedford Forrest W. Davis, named after the Confederate guerilla general and founder of the Ku Klux Klan. But Michael Hill doesn’t want to talk about the rebel flag-waving excesses of the student chapter: They are, he says, just boys. He wants to justify the righteous ways of the Southern League in its fight against “the Bush-Clinton New World Order,” affirmative action programs, “exorbitant taxation,” and other diseases of the Yankee Leviathan: “What we’d like to see, basically, is regional cultures respected,” he says. “There was a Southern nation before there was a United States and there will be a South long after the American Empire collapses on its own hollow shell.”

Hill argues that consumer capitalism has failed the South, traditionally a rural, communitarian society. He says Southerners should “abjure the realm,” opt out of the “cesspool of modern culture—throw the TV out of the window.” He thinks both the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the South in their lust for centralized government controlling the citizenry. I point out that he sounds like a sixties radical, and he allows as how he did come up during the years of dissent: of course, he reached vastly different conclusions from the hippie left. He read Mao and Lenin; Gramsci was, he says, a goldmine of ideas.

Hill is a historian by training and by profession, a scholar of Celtic warfare who got his B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Alabama. He was much influenced by conservative Constitutional scholar Forrest McDonald and historian of the “Celtic ways in the Old South,” Grady McWhiney, now at Texas Christian University. McWhiney’s book Cracker Culture is a central text for the Southern League, celebrating, says Hill, “the white Anglo-Celtic Southern culture,” rightfully “dominant” in the South, but now under attack from the forces of political correctness. McWhiney traces every tried-and-true Southern cliché to the “blood” of the Picts and the Gaels, the Brythons and the Scotii. In the introduction to Cracker Culture, Forrest McDonald declares that the Celts’ “entire history had prepared them to be Southerners.”

This is racial thinking, totalizing the complicated and gloriously miscegenous tangle of Southern society. It is also rejected by mainstream scholars. Historians like McWhiney, Clyde Wilson of the University of South Carolina, editor of the John Calhoun papers, and Hill, are revising the “revisionism” of the last 40 years, uncomfortable with acknowledging the cultural interlarding of native people, people of all sorts of European backgrounds, and, most importantly, African Americans.

When the Southern League says “Southern,” they mean white, they mean British-descended, they mean Confederate, despite Michael Hill’s careful insistence that he does not see Southern culture as “monolithic,” that African Americans have made contributions to it (the “New Dixie Manifesto” invokes Louis Armstrong and Ray Charles), that, in short, they are not racist.

Indeed, Michael Hill teaches British history at Stillman, a small Presbyterian liberal arts college. Stillman is a historically black institution. “My students love me.” Hill smiles like there’s nothing weird here, nothing unusual. “They flock to my classes.” He says he’s never made a secret of his politics. “I’ve always worn my little Confederate battle flag on Robert E. Lee’s birthday. The students ask, ‘What is that? Why are you wearing that?’ And I’ll tell them. They say it’s no big deal—you celebrate your culture, we celebrate ours. Like wearing an X cap.”

It seems a pungent irony that a man who believes in Old South values should be teaching kids who, if the Confederacy had won what the Southern League calls the War for Southern Independence, would not be in college at all.

Hill rejects the idea that the League longs for the old times on the plantation: “Not everything our ancestors did was perfect.” And yet the Southern League has made a fetish of the Confederate battle flag. And of Confederate “heroes.” The Dixienet site monitors “Heritage Violations,” yet another kind of “cultural ethnic cleansing,” or “presenting a hateful and revisionist version of the history of the Southern people and their struggle for independence,” removing a flag or a statue or renaming a street. They call Chancellor Robert Khayat of the University of Mississippi a “bigot” for suggesting that Ole Miss should re-evaluate some of its Confederate symbols, such as the mascot, Colonel Rebel.

In a letter to the “compatriots” dated March 3,1997, Michael Hill thunders: “Instead of educating Southern Confederate youth to be proud of their culture and heritage, liberal Yankee professors and administrators have taught them to be ashamed of their ancestors and thus to be ashamed of themselves. IT IS TIME WE MADE A STAND AGAINST THIS SORT OF CULTURAL IMPERIALISM, AND OLE MISS IS THE OPPORTUNITY TO DO IT.”

The League is not quite as unsubtle as Confederate Underground, a samizdat tabloid out of Memphis (the League does not produce it but they advertise in it, and student members, at least, distribute it). Confederate Underground’s articles are unsigned, and its politics smell of Old Klan rather than New Right. At the moment it howls with outrage over plans to place a statue of Arthur Ashe in his hometown of Richmond, finally integrating the white marble rows of Confederate generals. CU calls the planned image “the lawn jockey of Monument Avenue.” Michael Hill himself pitched a hissy fit when a historical marker went up in Montgomery, commemorating James Harrison Wilson, a Union general. He wrote to the local paper: “I wonder how the good citizens of Washington, D.C., would react to a Jefferson Davis Memorial placed next to the Lincoln Memorial. Personally, I would hate to see President Davis in such low company.”

Right now the League’s main scrap is over the Confederate battle flag. They are mobilizing against the Cracker Barrel restaurant chain for removing objects with the battle flag from their gift shops. They are railing against “cowardly” South Carolina Governor David Beasley who, in 1996, decided that the battle flag should no longer fly from the capitol dome in Columbia. Former Alabama Governor Jim Folsom had the flag taken down at the instigation of black lawmakers and the (largely white) Chamber of Commerce, fearful of convention boycotts.

The League savages those who see the flag as racist, the banner of the Ku Klux Klan, the backdrop to George Wallace’s “segregation forever” speech. Gary Mills, professor of history at the University of Alabama, writes in The Southern Patriot: “The so-called Rebel flag is the flag of the South—the symbol of many good things about our culture and history that are dear to the hearts of Southerners white, black and red. It becomes racist only in the hands of a racist, just as a gun murders only in the hands of a murderer.”

Heritage or Hate?

By the time Michael Hill and I get on to the banana pudding, the great grandmotherly dessert of the white, black and, for all I know, red South, he asks me the central question of Southern social placement bearing all the weight of history, ethnicity, and class: “Who are your people?” It used to be “who’s your daddy?” but that sounds a little old-fashioned now, even for us.

The answer is: My people are Michael Hill’s people. I am an Anglo-Celtic white Southerner, descended from wearers of the gray on both mother’s and father’s sides. My great-great uncles Luther and Milton Tucker fought at the Battle of Natural Bridge, where 16- and 17-year-old boys from the West Florida Seminary scrapped with tired Union troops outside Tallahassee, the only Confederate capitol not to fall to the Yankees. My great aunt Vivienne used to run the Daughters of the Confederacy in Leon County (and tried for years to get me to join the Children of the Confederacy). The names in my family are Roberts, Gilbert, MacKenzie, Tucker, Taft, Vaughn, Broadwater, Bradford. We have skin like skimmed milk and red hair. I can sing “Dixie.” I have worn a hoop skirt.

It’s clear that Michael Hill, who describes himself as “an old hillbilly from North Alabama,” and I have a lot in common. We can talk about college football: he tells some good Bear Bryant stories; I am a Florida State fan. Like him, I despise the way the South is still largely an economic colony of what Clyde Wilson calls “the deep North,” a dumping ground for the toxic waste richer regions truck to us. Like him, I regret the South’s mall-and-McDonald’s-driven assimilation into fluorescent America. Like him, I resent the way white Southerners are stereotyped as dumb rednecks—even if some of us are. I detested the movie Forrest Gump, ashamed of how the rest of the world saw us as virtuously stupid unconscious conservatives. And I hate that “Anglo-Celtic” Southerners are assumed to be racist the way we are assumed to eat grits every morning, winter or summer, whether there are Belgian waffles on offer or not.

Despite the virtual apartheid of Northern, Western and Midwestern cities, the riots, the racist policing, the rest of the country, officially absolved from the past just as we are officially prisoners to it, isn’t surprised whenever a couple of white soldiers stationed at a Southern base shoot a black man for the hell of it, or a couple of white sorority girls stuff basketballs up their shirts and go in blackface and afro wigs to a “Who Rides the Bus?” fraternity social, or various people for various reasons burn black churches to the ground.

But we are guilty. Michael Hill and I can deplore the reduction of the complex culture of the South to one big cartoon lynching party (the Southern League blames the “national media” for this, even though CNN is headquartered in Atlanta, Dan Rather is from Texas, and Howell Raines, editorial page editor of The New York Times, graduated from the University of Alabama—scalawags all), but there is a new wilderness of intolerance growing up below Mr. Mason’s and Mr. Dixon’s metaphor-charged line; we are slipping our New South tether and running off back to our Old South ways. A cross was burned on the lawn of The Crimson White, the student newspaper at the University of Alabama, in January 1996. A black professor in Tuscaloosa, a woman, was sent a threatening and racist anonymous letter.

And dozens of black churches have been torched over the last year, their shocked congregations recalling the vicious day in 1964, the nadir of the Movement, when a bomb tore the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Four of these chapels, Mount Zion, Little Zion, Mount Zoar and Jerusalem, smoulder in the Alabama Black Belt hamlet of Boligee, just down the road from where Michael Hill and I sit, being polite to each other over bottomless iced tea.

“Diversity has become the greatest threat to our survival as a people that we have ever faced,” writes Michael W. Masters, chairman of the Southern League of Virginia, in an essay called “We Are A People.” Yet Michael Hill, in a speech to a debating society at the University of Alabama, appears comfortable with diversity, asking “What would American literature be without Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, William Faulkner, Walker Percy, and Eudora Welty? What kind of popular music could we listen to if white ‘crackers’ like Hank Williams and Merle Haggard and Southern blacks like Louis Armstrong and Ray Charles had been content with the bland commercial music turned out by Tin Pan Alley?”

Michael Hill says the Southern League is not a militia (“I don’t even know anyone in a militia”), and yet he was quoted in The Wall Street Journal at a rally in South Carolina, wallowing in rhetoric the Montana Freemen would not be ashamed of: “Our enemies are willing to kill us. It is open season on anyone who has the audacity to question the dictates of an all-powerful federal government or the illicit rights bestowed on a compliant and deadly underclass that now fulfills a role similar to that of Hitler’s brown-shirted street thugs in the 1930s.”

On the Dixienet page “Hatemongers Not Welcome,” the League distances itself from the hyperlinking of its website to the Aryan Nations’ “Stormfront,” rejecting a “race-hate agenda,” then attacks the “persistent campaign of hate aimed at Confederate symbols by the NAACP and other black racial extremist groups.”

As ever, we come back to the question of race, the sorrowful central story of the South—of the nation really, but so much more graphically articulated in the world that slavery made—the narrative we try to avoid, to consign to a past that won’t leave us alone. Michael Hill gives me the user-friendly stuff, about as fire-eating as your average issue of Southern Living, knowing on the one hand that I’m white like him; knowing on the other hand that I’m one of those traitors who has stolen the discourse on the South with our African-American studies courses and our slavery-centered readings of the Civil War and our feminist assessments of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Gone With the Wind.

It might appear that there is deep confusion in the Southern League over race—maybe they believe their own bumper sticker: “Heritage Not Hate.” But calling blacks “a compliant and deadly underclass,” implying they are both brainless and violent, referring to the NAACP as “extremist”—the Southern League embraces the politics of white rage during the Reconstruction when the Klan rose up to “defend” the South against the federal government and its “unnatural” notions of equality, integration and opportunity. The Southern League sells hysteria as history. It doesn’ tmatter to them that George Wallace hoisted the Confederate battle flag in Montgomery to spite Bobby Kennedy and the whole integrationist project in 1963. They act like the thing has been flapping in the wind over the dome since Jeff Davis stood on those white marble steps and proclaimed secession. It doesn’t matter that there were (large) parts of the South that did not secede, that were not Anglo-Celtic, that were not even English-speaking. It doesn’t matter that the very Southernness they cherish is a product of cultural miscegenation; our speech, the food we eat (yams, okra) and our music come from the close (though unequal) interaction of white and black. The Southern League clearly longs for the time when men were men, women were ladies, and black folks knew their place.

Michael Hill’s genteel academic restraint is the exception. I met the Tuscaloosa chairman of the Southern League, David Cooksey, at a debate on the University of Alabama campus. He’s a big, light-eyed guy with what’s called around here a “country” accent. He sells Little Debbie snack cakes for a living. Cooksey got notorious in town for flying various Confederate flags in front of his house. When a white student at the meeting suggested that those banners might be offensive, he leapt to his feet saying “Negroes” threatened him with death for exercising his constitutional right to freedom of expression. In the pocket of his plaid shirt he had stuck a little battle flag on a gold-painted stick. If he fell down, it would have stabbed him right through the heart.

At my second meeting with Michael Hill, in a studio at the university radio station, he’s less careful than before. He deplores the “attack” on Anglo-Celtic culture and “traditions” that began about 40 years ago—that being the time of the Civil Rights Movement. He says that interracial marriage is wrong because it “dilutes” both races. He says the Southern League is against affirmative action; he implies it has little time for democracy as well: “You know the South has never bought into the Jacobin notion of equality.” He says there is a “natural hierarchy, a natural social order.” Just because “one group” is on the bottom does not mean it will be mistreated. People find their levels, Hill says.

This echoes the speeches of Pat Buchanan, the presidential candidate the League liked best (though they do not officially endorse) Buchanan once mused about whether it was better to have “10,000 Englishmen or 10,000 Zulus land in the state of Virginia.” Michael Hill looks hard at me; I know what he’s talking about. And he knows I know. This, like Willie Horton, like the pale hands tearing up the job rejection letter in Jesse Helms’ infamous TV ad, is white code.

It is no freak of resurgent racism that the Southern League’s chosen battleground is the university, where the ownership of history is always disputed. But the disaffected historians the League is top-heavy with don’t speak only to each other with books called The South Was Right! and position papers explaining that “the War of Northern Aggression was not fought to preserve any union of historic creation, formation, and understanding, but to achieve a new union by conquest and plunder,” or revealing that the abolitionists were socialists, atheists and “reprehensible agitators” whose commitment to equality is to be deplored as “unnatural.”

Like the paranoia of the anti-government militias, the recasting of the white South’s past as a combination of triumph and victimization poisons the general waters. Michael Hill’s contention that “anyone who is honest” and understands the 10th Amendment will see that “the South’s position, constitutionally, in 1861was the correct one” feeds the sullen return of attention to states’ rights.

Alabama State Senator Charles Davidson, who briefly ran for Congress, may not be a card-carrying member of the Southern League (Michael Hill says that though he helped Davidson’s office with some “facts,” he is not acquainted with the senator), but his notorious speech, excerpted on every wire service in the country last May, displays the logical conclusions of the Southern League version of history. Davidson argues that the abolitionists were obviously wrong because slavery is in the Bible and so they cannot “call something evil that God obviously allows.” He goes on: “To say that slaves were mistreated in the Old South is to say that the most Christian group of people in the entire world, the Bible Belt, mistreated their servants and violated the commandments of Jesus their Lord. Anyone who says this is an accuser of the Brethren of Christ. Not a very good position to take.”

The old easy, urbane, Northern dismissal of Southerners is that we are still fighting the War. Maybe we are, though I think the War metamorphoses every generation or so into something that tells about the South of the moment, the South of our present making.

The South is like a cellar for all the old stuff—a class system, racial inequality, rigid gender roles, vigilante violence, history itself—the rest of the country decides is worn out or embarrassing (they just buy themselves a new model). Old times here are never forgotten. But thes tuff doesn’t go away—it isn’t biodegradable. It’s right under the floorboards, down there: you don’t even have to dig tofind it.

The Olympic flame in Atlanta was supposed to illuminate the New South, the South of sunbelt business, of black mayors in great cities, of integrated institutions. But it should also remind people of the burned churches, piles of charred hymnals and pews reduced to ashes that dot the Old Confederacy.

What do we do with all this history? All this pain? You can’t eat magnolias; you can’t get dignity from a scrap of red and blue cloth with white stars crossed on it. The Southern League marches on, another dinosaur joining our Dixie Jurassic Park, another living fossil for the political tourists to stare at, and hear thee cho of Faulkner’s Anglo-Celtic Hamlet, Quentin Compson, sitting in his cold Harvard room crying, “I dont! I dont hate it! I dont hate it!”

Tags

Diane Roberts

Diane Roberts is a writer, radio commentator, and the author of The Myth of Aunt Jemima. (1999)

Diane Roberts is author of several books and a professor of English at the University of Alabama. (1997)