This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 1/2, "Southern Media Monopolized." Find more from that issue here.

Ms. Barr, I want you to know that I will do your memory no harm. They call you “Mammy Callie” and say you weren’t anything but author William Faulkner’s Mammy, and a good one. I know you were more, that you have a history, a story and a reality.

Attempting to resurrect a woman who, in a lifetime, went from slave to free woman to neo-slave to prototypical myth is a daunting task. When the woman is Caroline Barr, Mammy Callie to the Faulknerian world, the task can be disheartening. With these notations and the above prayer, I began my search of her life. I soon came to realize that I would not meet Caroline Barr until I had spent time with her subservient shadow.

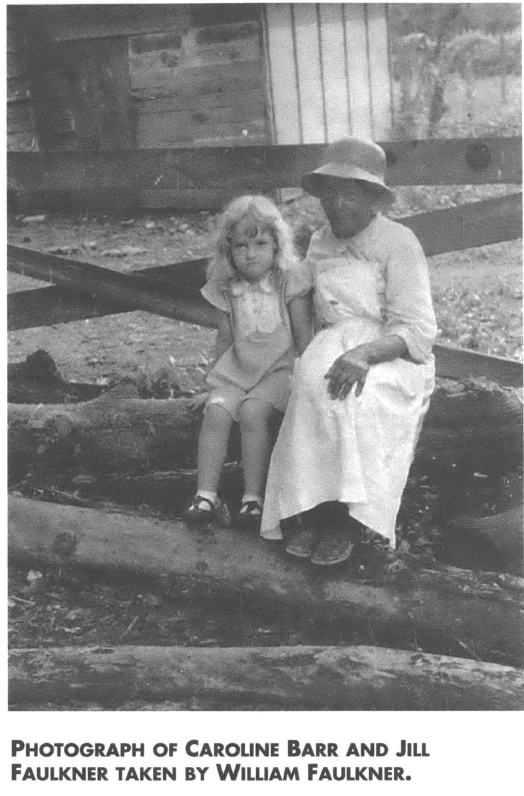

This silent shadow, Mammy Callie, is easy to find and research. She has been photographed dishing up ice cream to William’s daughter Jill, and posed stoically next to Jill on a log. At Rowan Oak, one may hear that Faulkner was so devoted to his mammy that he put central heat and air in the slave quarter she shared with other African-American employees (but the air conditioning unit is dated 1985).

At other times, curious visitors may be informed that she had “the cabin” (as the slave quarter behind Rowan Oak is euphemistically called) all to herself. To the images, historical untruths, and inaccuracies necessary to the construction of this mythical figure are the few lines she merited in Faulkner biographies and in his own short stories, including one which, undaunted by racist implications, alleges her nickname to be “Callie Watermelon.” Most of the texts are nostalgic and simply reveal Mammy Callie as the “glue of the Faulkner family,” the typical, salt-of-the-earth Mammy who had nobody but white bodies and was as faithful to them as Mississippi summers are hot.

When Caroline Barr the woman outran the myth, she was a loved and loving mother and aunt; she was also a trickster. This woman is not spoken of or known at Rowan Oak: She is not present in faded photographs or oft-fingered masterpieces, nor in the cabin behind the Rowan Oak home. The ink of Mammy Callie could not contain her. But Caroline Barr is present on the lips of her people, and in her community.

Oxford’s African-American elders prepared me to meet Caroline Barr by immersing me in an Oxford to which only communal members were privy—an Oxford booming with sound, vivacity, revolution, pride and communal bonding. I visited Oxford during the heyday of Freedman’s Town when “the square” (now overseen by a confederate soldier of stone) was a black thang. Through their eyes I witnessed the African-American man who held no signs, started no riots, just walked up to the courthouse and registered to vote like the citizen he was—in Jim Crow Mississippi. I sat with mothers and learned those “old timey” herbal healings of black thread, pine needles and dimes. I heard the rhythms and felt the vibrations calling us to “The Barbecues.” These well-reminisced gatherings called to black folk in Oxford with resounding African talking drums “you could hear all over Oxford” and with corn whiskey, jamboree and spiritual invocations. I visited with Molly Barr, sister of Caroline, a nurse and midwife with 11 children of her own who would take in and feed anyone in need. Gladly, Oxford’s oral libraries were and still are intact. They spoke these texts to me as they speak them every day.

I traversed the crossroads of Wiley’s Shoe Shop, the oldest black business in Oxford, to Mrs. Isaiah’s Busy Bee Cafe, to Caroline’s own distant nephew, James Barr of the Oxford Ice House, to finally her late niece Molly of Molly Barr Road to find. Caroline, the “Esu Eleg” of Oxford, an equivalent to the West African Trickster Orisha (deity) of linguistic wit and cunning.

I emerged through the crossroads in front of James’ Food Center where gray headed old patriarchs disguised as old men sitting on milk crates, informed me that Jake Barr might know something about the woman. If I came back at 3 p.m. I could find him out back with his truck filled with fresh produce waiting to talk to “a sweet little thing like [me].” Well, Jake Barr was impressed by neither my sweetness nor my purpose. He had heard tell of Caroline, and he knew that he was related, but he was young when she died. His sister, Rachel McGee, had known her well though, and he would take me to her house after he loaded his produce.

At Rachel McGee’s home, I parked my car and emerged scanning for dogs and eyeing the yard filled with flowers, shrubs and mementos from loved ones. She greeted me at the screen door, a heavy-set woman with smooth skin, close-cropped, regal white hair and a nice-sized butcher knife. I stammered out who I was and said that I wanted to know about Caroline Barr. I added that I had no interest in the glorification of Faulkner. We became fast friends. Then Rachel, the granddaughter of Caroline’s sister Molly and the daughter of Molly, her niece, began to share Caroline’s story.

Caroline Barr was born as a slave of the Samuel Barr family of Pontotoc, Mississippi, circa 1840. After the Civil War, the Euro-American Barrs remained in Pontotoc while the newly freed slaves traveled to Oxford. Murry Faulkner (William Faulkner’s father) and Samuel Barr (or his brother) were friends if not business partners, and through this acquaintance Caroline’s family made the move. Her brother, Ed Barr, was working as a tenant farmer on Murry’s “Greenfield Farm” when Caroline joined him in 1900 or 1901. Caroline began working for Maud and Murry Faulkner as a caregiver in 1902. William was five and Caroline would have been in her early forties.

Prior to coming to work for the Faulkners, Caroline Barr had lived a full life, including marriage to a man named Clark, and three daughters, Fanny, Millie, and Carrie, all of whom were grown and living in Batesville, Tunica, and Sardis, Mississippi (respectively,) when Caroline came to Oxford. Rachel McGee recalls that Caroline’s children were the spitting image of their mother. Caroline relocated possibly after the death of her husband and specifically to be near her Oxford relatives like her brother Ed and her niece Molly Barr.

“I know what I’m tellin you is right. Now all that other mess they puttin’ out I—umm-mm . . . I don’t know nothin’ about it, they just makes stuff up.” Rachel McGee is lucid, feisty, open, and remembers her great aunt well. She told me, “Yeah, they come here all the time [historians and biographers], want to know about Faulkner, what I remember ’bout Faulkner. Faulkner. Faulkner.” They never asked about the black mammy who could not possibly have a story to tell, so they fill in the cracks with little white lies. However, with oral librarian and great niece Rachel McGee, the caulk crumbles and a three-dimensional Caroline Barr takes form.

Rachel remembers her aunt as petite and having a “high temper, Whoo! And she carried a little pocket knife. She’d get you with that pocketknife. Aunt Callie didn’t stand back, she’d tell ’em what she think. She was a mean devil and would fight—wasn’t big as a wasp and would fight and cuss!” Laughing, Rachel recalls, “I don’t remember her singing, or telling stories but she could cuss up storm!”

Mildred Quarles, Rachel’s daughter, recalls that her great-great aunt would get you with a switch. “Aunt Callie sho was hard on me. Me being the only girl and all. Oh, she would whoop me and tell me to stop fassin or to keep my dress pulled down. She tryin’ to teach me proper manners.” Such lessons were for all her progeny and were taught from home to cornfield. “We would all be out there, makin’ our crop,” Jake recalls, “and she’d have a switch right handy for our legs when we showed out—”

“Sho would” chimed Mildred. Their laughter shook Rachel McGee’s home. Caroline Barr’s text emerges not as one of earth salt and knee-rockings but of tough survival skills.

It has been said and it may be true that Barr was a repository of folktales that she shared with the Faulkner children. But it is significant that the Barrs do not recall their aunt telling any tales or singing any songs. Caroline’s family remembers her taking care of business and seeing to the beneficent construction of her family. This inconsistency marks the pattern of duality that was Barr’s existence: Mammy Callie for the Faulkners—an entity of humor, wit, levity and a source of stability in an often shaky home, and Caroline Barr for her family—the woman who found release and respite at her communal home where her plight was understood and where her stabilizing power was welcome. Unfortunately, it was the side of existence most fitting racist Euro-Southern fancies that became glorified.

Rachel McGee’s most vivid memories of her great aunt are those of Sunday visits when she was a child. “Aunt Callie would come up to my mom’s every Sunday. They would come through the week too, but I ’member ’em coming every Sunday cause I could see ’em walkin’, ya know. See Aunt Callie, William and Dean would come every Sunday at nine o’clock. I know it was nine cause I could hear the church bells ranging. Oh, they stay all day.” With white bonnet bobbing away, Caroline Barr would take the Faulkner boys with her to visit her niece. Caroline was embracing her family and fellowshipping at her roots. For sure, her intention had nothing to do with providing William the fodder to pen the church scene of The Sound and the Fury or to smell the rancid fecundity that he would characterize as ever-present in the African-American home.

An ironic ex-slave, Barr’s status was alternately mammy and woman. The literary community knows Mammy Callie by her apron and bonnet—articles of clothing she was never without. But under this necessary costume that professed she was all that she pretended to be—Caroline Barr layered lives, experiences, and necessities. While keepers of the Southern mystique were admiring Mammy Callie’s portraiture, Caroline Barr was running smoothly through the black ink to her own life and family. The duality of her existence is apparent in her infamous and oft-scandalized running off to various lovers. Here Caroline Barr and Mammy Callie meet—in the body of a 70- and 80-year-old, free black woman who felt compelled to run from her “masters” as would a slave.

William Faulkner recalls her fleeings in a letter written to Reverend Robert Jones two months after Caroline’s death (now housed at the Armistad Research Center, Tulane University). Faulkner recounts that “in 1919 she left us for a year. She never gave any reason. She just informed us one day that she was going to marry . . . and was going to live in Arkansas.” He elaborates on the cause of this sudden development: “I saw later what the reason was—a psychological change, almost a violent overturn, in the inter-relations not of the family and her but in the family itself. . . . The two oldest children had become soldiers in 1918 and Dean, the youngest, no longer needed her care at age ten.” Faulkner postulates that this familial overturn, coupled with feelings of uselessness, culminated in Caroline’s alleged marriage in Arkansas.

I read the above incident to Rachel McGee. She laughed sardonically. “I don’t know nothing about that”—this from a woman with a memory lucid enough to vividly remember most details of her childhood. Would she not remember her aunt’s sojourn and marriage in Arkansas? Furthermore, what would her family have said about their 70-year-old aunt hooking up with some man in Arkansas? William himself gives insight to the validity of this “memory” when he mentions “a little Arkansas village” and “Mammy, walking up the road toward the station with her suitcase on her way back home.” While this makes for good reading—a tragic tale of the mammy who thinks she has outlived her usefulness—it does not make for fact. As I shared more of Faulkner’s construction with Rachel McGee, it became apparent that Caroline’s motivation to leave had little to do with the Faulkners or their tragic familial upheaval.

William continues his textual construction of Mammy Callie as he writes of Caroline’s visits to her children who lived in Batesville: “Two or three times [sic] a year she would decide to visit among her children, two of whom lived some thirty miles away. Sometimes she would tell us she wanted to do this, and we would send her by car; sometimes, she would not even tell us, she would just be gone one morning, and we would find out later that she had walked the entire distance, and she was close to 80 years old then. And then the Arkansas situation would repeat itself again.”

“No,” Rachel McGee broke in, “she would come out to my mother’s just to stay away from ’em, you know. She told my mother, ‘If William them come, don’t tell em I’m here.’ She gettin’ her rest, you see!”

Ironically, the myths of devotion and accountability William constructed for Mammy Callie were the results of Caroline Barr’s doing what she wanted and needed to do. She had learned from slavery that it was suicide for masters to be privy to the inner workings of the slave community. When she wanted to visit her children, she was driven the 30 miles to their homes until, as Faulkner says, “My mother would stand it as long as she could, then she would send a car to fetch Mammy home.” So when she wanted to completely leave her employers’ reach, Caroline did not go far; she just crossed Oxford’s backroads to visit Molly and her Oxford family. She disappeared under the guise of the resilient, mile-walking, lascivious, man-lovin’ mammy.

Continuing with Faulkner’s construction of his and his child’s caregiver, we find Mammy Callie in rare form, just prior to her death. “She and the little girl [his daughter, Jill] were both very fond of raw tomatoes. For breakfast that morning, so I learned later, they [sic] two of them ate together three quarts of them sprinkled with sugar and in ice. Later that morning they ate a watermelon also iced. That afternoon they ate about a quart of ice cream. That night she [Caroline] told me her stomach didn’t feel right and she wanted some whiskey, which I gave her.”

Caroline Barr’s family members and history make it clear that her eating habits in no way reflected any measure of gluttony. Upon hearing this, Rachel and Mildred never called William a liar but the house shook with a laughter to dry tears. It is one thing to tamper with one’s memory; it is another thing altogether to make a grown woman out to have the mentality and habits of a child.

Faulkner continues: “The next morning the houseman, who lives with his wife across the hall from her in her house, waked me at daybreak and told me she was ill.”

“Never been sick a day in her life.. Caroline’s great-niece interjects.

“. . . We got the doctor, and she had a pretty severe spell of it, what with her age. I sent for her family, her house full of four and five generations of them, the backyard full of strange children and she lying in bed convalescent, quarreling and fussing at them, then, sitting on the gallery, being waited on hand and foot and still quarreling, scolding at them for disarranging her things, sending up to the house at 10 and 11 and midnight wanting ice cream (she liked strawberry) whereupon I would have to get up and dress and drive in to town and fetch her back 10 cents’ worth. . . .”

If four and five generations were at this ice cream social/family reunion-on-the-heels-of-death, key people, Molly Barr, Rachel McGee (about 32 at this time), Mildred Quarles, Jake Barr—all direct and linked family members—were strangely absent. No Barr knows anything about this alleged “illness” or this gathering. This text is nonexistent in Oxford’s oral libraries.

Perhaps to lessen the sting of what she had just heard, and maybe because we still exude the cautious ways of the trickster, Rachel McGee attempted to say something positive on Faulkner’s behalf. “He was good to Aunt Callie when she died.” The morning of January 31, 1940, Faulkner called McGee at the home where she worked and still works and told her Caroline had died of a paralytic stroke. He said to Rachel, Caroline’s nearest relative that he knew, “Don’t worry about a thing, I’ll take care of everything. . . .”

Faulkner held a funeral service for Mammy Callie in his front parlor. After this, Caroline Barr traveled to Second Baptist Church to be received, finally, by her family. “Oh she was dressed,” recalls Rachel.” White silk dress and white silk head bonnet.” Faulkner would write that she was laid to rest “in the cemetery here beside her brother.”

“Ain’t no brother out there,” Rachel, no longer hiding her disgust, spat. “Ed Barr, that’s her brother. All the Barrs is buried out here in St. Peter’s—black neighborhood—out here on College Hill Switch. I can take you out there.” It hurt—not just to hear the memory of an ancestor defiled, but to hear it done with such arrogance. Then, Rachel McGee finally said, “I’m sick of hearing them lies.”

The peace she sought has eluded Caroline Barr even in death. Faulkner told Rachel McGee that he’d “take care of everything,” and he did. In handling her burial arrangements, Faulkner wiped Caroline Barr out of existence. Hodges’ Funeral Home record reads:

Number 161: Callie Clark (2-4-40),

Colored; 93 years old;

Died in Lafayette County, St. Peter’s;

Voting Precinct, Oxford; Name of Purchaser: William Faulkner; Name of Nearest relative: “Clark”; Address: Oxford; Relation: Daughter.

Why, in death, would William exclude Caroline’s family? Why would he excise her ancestry and history? Natal alienation is a facet of the definition of a slave, as is being generally dishonored.

Mr. Hodges of Hodges’ Funeral Home and I trekked all over St. Peter’s Cemetery, the black and white segments, in search of Caroline Barr’s gravesite. Caroline, Ms. Barr. I know you are out here! Laughing at me, I can hear you. 1 have to smile myself. Where are you? Back and forth we went, from the black sections to the white scanning mausoleums and tombs and meeting laughter. I’m almost finished. I have found you, everywhere but here. I will do your memory justice. Please let me find you.

We found her as close as she could be to William in a segregated cemetery. Her grave marker is about 12” x 10” of gray marble, about two inches thick. It reads:

Callie Barr Clark 1840-1940

“Mammy”

Her white children bless her.

William Faulkner’s desires locked Caroline Barr forever under the designation of Mammy Callie. Locked in a slave’s place, Caroline Barr is as physically far from her family—her brother and niece and daughters—in death as in life. Defiled in death with a marker that does not even bear her given name, Caroline Barr still must go through the crossroads of Mammy Callie to meet her officially excised relatives and her self.

I want to shout: Her name was Caroline Barrrrr! But who will hear? Who hears her voice through all of the lying literary layers draped around the shadow of a woman too swift to be penned down, a woman who still bleeds through the ink of a fragmented myth who served purposes and others? Pages of conveniently misnamed, thick, American, Pulitzer-approved pages of lying muffle a voice only a few family members recall.

Still, William had a mammy, but he did not have Caroline Barr. He did not have the Aunt Callie that Rachel had on Sundays. The woman who gave Mildred Quarles switch-induced instruction on how to be a young lady, the one whose discipline helped make Jake a lucrative produce farmer, and the woman who helped with those infamous Oxford Barr barbecues was not Mammy Callie. No, the woman who impacted her family’s life with tricksterian instruction and simple reality was never present at Rowan Oak—that was just her shadow. Her spirit is not in St. Peter’s —those are mere ashes.

Tags

Teresa Washington

Teresa Washington, a native of Batesville, Mississippi, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin. (1997)