Between the Cracks

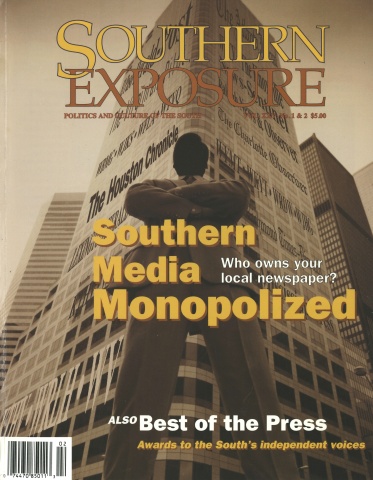

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 25 No. 1/2, "Southern Media Monopolized." Find more from that issue here.

The Courier, Houmas, LA

First in series published September 2, 1996

Jackson, Louisiana—James Anderson has been quiet lately. Correction officers at the Terrebonne Parish Jail say he hasn’t thrown feces at them in awhile or displayed any of the other bizarre behavior that led to frequent housing in an isolation cell since his Nov. 14, 1994 incarceration on a robbery charge.

Doctors found that Anderson, who has a long history of mental illness, was incapable of standing trial and reported those findings to state District Judge John Pettigrew of Houma.

On Oct. 25, 1995, Pettigrew ordered Anderson committed to the Feliciana Forensic Facility, a state-run mental hospital in Jackson. Once there, Anderson would receive care from doctors, nurses and other professionals who would treat his illnesses and try to bring him to a point where he might be able to go ahead with his court case.

He never went there.

Now, nearly a year after Pettigrew’s order was issued, Anderson spends his days lying on a bunk, staring at the ceiling. Correction officers who see him every day say he appears “off in another world.”

Anderson is one of 61 inmates in Louisiana receiving minimal mental health treatment in jail because there is no room at the Jackson hospital. They have waited months and even years for a bed at the hospital, locked in what experts describe as a mental health crisis in the state’s criminal justice system.

The inmates, including three currently in the Terrebonne Parish Jail, have been ordered to go to the state hospital by a judge upon the recommendation of a court-appointed sanity commission. The panel—at least two but usually three doctors— has found that the defendant cannot assist their attorneys in handling their cases because of mental disease or defect.

For centuries, the law has recognized that people who are mentally ill may not be able to understand the charges brought against them. Their conditions often prevent them from assisting their attorneys in preparing a defense or even deciding whether to plead innocent or guilty.

Lawyers and doctors note that being deemed incompetent to stand trial is not the same as an acquittal by reason of insanity.

“The public generally does not understand the difference,” said John Lavern, president of the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “They tend to think of someone who’s gotten off with a crime because of momentary insanity. If they really knew what the difference was, they’d want these people in treatment getting well.

“As soon as I walk in a courtroom filing papers in these cases, people say, ‘He’s trying to get off with something,’ and that is not the case,” said Lavern, who is also the public defender for Calcasieu Parish.

“The issue of whether or not this person is competent to participate in legal proceedings is the same difference as if you were bringing a 3-year-old child in there and making that 3-year-old knowingly participate. But they don’t want to spend money on health and hospital settings for these people because they perceive the person is saying, ‘I was crazy at the time, but I’m OK now,”‘ he said. “If you put him in a hospital setting you restore him to a level of competency where at least his lawyer is able to explain things to him, and then we can go ahead and have a trial.”

Thomas Litwack, professor of psychology and law at New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said definitions of competency are more or less the same across state lines.

“The basic issue is whether this person has the ability to understand his or her legal situation in a rational as well as factual way,” Litwack said.

Federal case law, Litwack said, requires that the defendant have sufficient ability to consult with his attorney with “a reasonable degree of rational understanding.” The defendant also must have a “rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him.

“That’s the basic test everybody accepts, and it is generally understood that if you get a defendant who would clearly become incompetent under the stress of trial, even if he or she is currently competent, the courts are uncomfortable because they may not be able to get through the trial,” he said.

Judges routinely order such defendants to the Feliciana Forensic Facility. But the court orders are just as routinely ignored. State health officials acknowledge the admission delays and attribute them to lack of beds.

A Courier investigation into how the system works in Louisiana has revealed the following facts:

▲ Jail inmates deemed incompetent to stand trial wait long periods of time for beds in a state hospital that was designed to address their specific needs and problems. Jail-based treatment— not to exceed 90 days—may be given by the state to such patients. But after that time, according to state law, they should go to the hospital and not remain in jail. Most inmates in Terrebonne Parish who have been declared unfit to proceed with their cases have spent in excess of a year in jail, waiting for beds that don’t become available, records show. One man spent nearly three years waiting.

▲ Sixty-one pre-trial detainees, including the three in Terrebonne, are on a waiting list statewide for a hospital with only 75 beds that are constantly filled. Feliciana hospital admits an average of 90 patients a year.

▲ Efforts by the state’s Department of Health and Hospitals, through the Office of Mental Health, have been made to correct the problem of long waiting lists. But nationally recognized experts question whether those efforts serve the patients’ best interests.

The problem is money.

Heightened Cynicism

Local elected officials are well aware of the situation but say they’re powerless to do anything about it because the responsibility lies largely at the state level.

“We’re making our own statement by underfunding,” said Terrebonne Parish District Attorney Doug Greenburg. “The people in this horrendous position are not given the same treatment other people are. I think the entire criminal justice system needs to take a long look at it, and I don’t suggest it’s because they don’t care about this. The demands on the system are case-by-case, and they come in droves.

“If you are dumping back into the system persons who are not really treated or recovered to the definitive competence level that’s necessary to comply with our prerequisite that you have mental capacity to proceed, then you have done nothing more than occasioned the further breakdown of the system, the further loss of large sums of time, energy and money and, worst of all, no justice. You get a society funding this not only to come up with no reasonable result but a worsened or a heightened cynicism.”

The Bottom Line

Greenburg sees a lack of money as the bottom line.

“No one would have used cost-effectiveness to determine the sentence to be administered to someone, but that has become a very functionally considered aspect of incarceration.”

The mental health crisis in the criminal justice system puts prosecutors in a peculiar position, Greenburg said. Knowing that the rights of mentally ill and perhaps incapacitated defendants are already compromised, the district attorney’s own assistants have at times petitioned to have those defendants declared incompetent—a role the prosecution may surely take but which is traditionally left to the defense. “

We have without our own volition or desire been expanded into the role where we are no longer on the prosecuting end. We are situated in the position where we now have to do an overview of the whole case so that nothing can be said later on that there was ineffective assistance of counsel, that someone on the defense side didn’t do his or her job,” Greenburg said.

“That’s not really the state’s job,” he added. “We are being put into the role of prosecution and defense counsel and being asked to make a determination of a psychomedical nature that we’re not qualified to do.”

Greenburg suggested that the numbers of inmates who have been declared incompetent—and then can’t get into the hospital beds the law says they should have—could represent just the tip of the iceberg. He notes that about 40 percent of jail inmates receive medication, and some could require additional attention for psychiatric and psychological problems.

Terrebonne Parish Sheriff Jerry Larpenter, along with his jail administration, said they are frustrated by a system that is calling on them to provide medical treatment rather than incarceration, resulting in an increased strain on their resources.

“The sheriffs around the state should not be in the business of keeping mental patients. We don’t have psychiatrists on hand, although Mental Health comes occasionally. They determine the medication and the staff has to give the medication out, but it’s just a staging area in order to get them help when they deserve it,” Larpenter said.

As a result of The Courier’s series, the Louisiana State Legislature’s criminal justice committee conducted hearings at the urging of Rep. Reggie Dupre (D-Montegut) on the subject.

Legislation that will protect such inmates in the future from being lost in Louisiana’s justice system as a result of those hearings—and the articles—has been drafted and is pending before the state’s house of representatives.

Anderson: Robbery, jail and a dirty towel

James Anderson, one of the many mentally ill prisoners at Terrebonne Parish Criminal Complex, had a history of mental illness before his current incarceration for robbery. In 1994, he robbed a Circle K store of $357.47 in cash and merchandise, including 10 cartons of cigarettes, 50 lighters, a case of Milwaukee’s Best beer and nine bottles of Crown Royal Whiskey.

In 1980, Anderson was prescribed the drug Elavil after being hospitalized at Charity Hospital in New Orleans for depression. During the same year, he was reportedly diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, medical records show.

In July 1995, a sanity commission report was filed in court by Dr. Dennis M. Spiers, a Houma psychiatrist, who was told by deputies that Anderson often displayed bizarre behavior and had been kept in a state of continual lockdown. His worst offenses included throwing feces at guards and other inmates.

When the doctor saw Anderson, he appeared disheveled and kept his beard and hair in braids. The inmate also had a “wide-eyed” facial appearance.

“He had a dirty white towel around his neck and pieces of cloth (which looked as if they might have torn from the towel) stuffed in both ears,” the doctor wrote.

Spiers found a diagnosis of probable psychotic behavior.

“Based on the limited information that he gave me, he does not seem to have complete comprehension of the charges against him,” Spiers wrote. “It would also appear that it would be markedly difficult for him to cooperate with his attorney and assist with his own defense. It would certainly appear that he might well be a candidate for a referral to a state forensic unit for further evaluation and possible treatment.”

—J.D.

OTHER WINNERS (Investigative Reporting, Division One): Second Prize—Lenora LaPeter of the Hilton Head Island Packet for her series exposing the billing of black residents of Hilton Head for utility services they never received. Third Prize—Jenni Vincent of the Times West Virginian for the “Bleeding Earth” series examining the impact of coal mining in North Central West Virginia. Honorable mention—Geiter Simmons and Mark Wneka of the Salisbury Post for an in-depth look at the background, legal ramifications, and history of redistricting and black congressional districts in North Carolina.

Tags

John DeSantis

The Courier, Houmas, LA (1997)