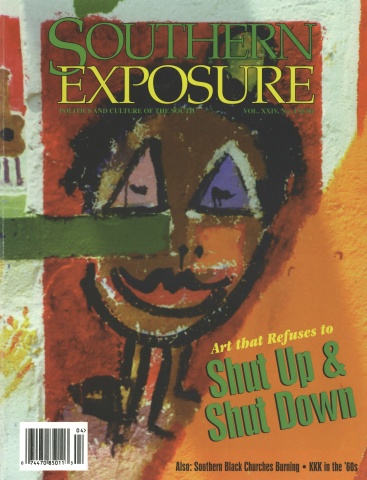

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Port Gibson, Miss. — The liveliest spot on Fair Street and the most recent object of controversy in a continuing racial conflict over control of public space in Port, Gibson, Mississippi, is a full-length mural which decorates the side of a previously abandoned building. In a town working to rebuild the downtown area and promote local culture to attract tourists, the mural project, which replaced the cracked, dirty, and unappealing wall, seemed like an ideal project for widespread community support. Instead it has been the latest subject of scrutiny and controversy in this rural, majority African-American community in Southwest Mississippi.

The storefront of Mississippi Cultural Crossroads (MCC) faces Main Street, which is the traditional white center of commerce and power. The mural side of the building runs along Fair Street, which was once known as “Nigger Street.” As its location suggests, MCC, in some senses, serves as a literal connector between white and black Port Gibson. It is an integrated cultural arts organization with a commitment to African-American history, culture, and aesthetic as an essential part of an integrated and complete community. Through its racially inclusive programs and presentations, MCC has become a sort of touchstone for revealing many unspoken assumptions which still divide blacks and whites, and subtly challenging the sometimes hidden remnants of white dominance.

The mural was created in large part by children and adults in the community, both black and white. It is bright and colorful and includes children’s self-portraits and large jaunty letters spelling out Mississippi Cultural Crossroads. It portrays 18 years of various MCC programs (Peanut Butter and Jelly Theater group and Summer Art Program), black and white individuals, and downtown landmarks traditionally associated with blacks (Our Mart, a black-initiated cooperative grocery store), whites (Presbyterian Church with a finger pointing to the sky), and with both communities (Trace Theater, owned and frequented over the years by whites and blacks). It is through its very racial inclusiveness that the mural diverges from the conventional white idea of the community’s important history and culture.

The society and architecture of antebellum days and General U.S. Grant’s oft-quoted comment that Port Gibson was “too beautiful to burn” tend to dominate the community’s image to tourists and to some extent its self-image. In an effort to attract tourists, Port Gibson is deliberately working to promote its history. The integrated Main Street Organization, dedicated to rejuvenating the once-thriving downtown area, and the integrated City Preservation Commission, charged with maintaining and preserving the integrity of the community’s history and culture, are the civic organizations charged with leading this effort. Both organizations are signs of a growing commitment by black and white civic leaders to create a harmonious integrated community where public policy considers and benefits both races.

At times, however, the Preservation Commission’s charge to “strengthen civic pride and cultural stability” and “preserve, enhance, and perpetuate those aspects of the city . . . having historical, cultural, [and] architectural . . . merit” raises difficult questions which test the tenuous peace. Mostly unspoken, these questions can reveal the differences between whites and blacks that otherwise tend to remain submerged in the cautious terrain of 1990s politics and polite, careful conversations about an integrated town and interracial harmony.

This is evident in the community’s response to the mural and related work. After a lengthy meeting with the Preservation Commission, the constitution of a mural subcommittee, and negotiations about the mural’s content, MCC’s request for a required “certificate of appropriateness,” or permission to alter a historic building, was granted, and painting began in late May 1996.

Painting the Bollards

The three-week project involved two weeks of art instruction and painting for local schoolchildren. By the end of the first week the children had painted everything they could reach, so mural artist Dennis Sullivan decided to have the children paint the sidewalk squares in front of the mural. The children maneuvered around the cracked and broken cement and covered years of dirt and neglect with cheerful and vibrant images of their homes and families and favorite musical instruments. These images brightened the sidewalk and commemorated the history of Fair Street where African Americans had gathered (through the 1960s) to visit and listen to top rhythm and blues acts playing in local juke joints.

In a final burst of enthusiasm, Sullivan and others also painted small posts (called bollards) that separated the street from the sidewalk in front of MCC on Main street. Originally white, the painting crew left them a variety of bright colors.

Reactions to the project came quickly and varied widely. The white city clerk articulated her dismay by saying, “Look what they’ve done to our sidewalks!” She asked the chief of police to research local laws to see if Mississippi Cultural Crossroads should be charged with destroying public property. A white banker and member of MCC’s board was pleased with the mural and thought the sidewalk was O.K., too. But, he reported objections to the colored bollards with the simple explanation: “White only on Main Street.”

A retired black schoolteacher liked the bollards’ new range of colors and got right to the heart of the matter by volunteering to repaint them, not their new array of colors, but black, if they were restored to their earlier uniform white. A young African American who participated in the painting brought more than 50 of his relatives, in town for a family reunion, to view the mural and admire the parts he had helped paint. His mother, a member of the Preservation Commission, was pleased with the mural as a visual addition to downtown, but also for the way it connected her son to the community.

These comments and reactions were fairly typical and, as I listened to them, I was struck not simply by the divergent reactions, but the sense of ownership, entitlement, and assumptions of control that many white comments conveyed. In this regard, the mural, though perhaps more subtle, raises important issues of authority and control reminiscent of the community’s civil rights movement.

Whites and Spenders Only

Before the civil rights movement, Main Street, the commercial center of Port Gibson, was almost like a private drive for the white community whose merchants and farmers dominated the community’s economic and political power structure.

Like temporary guests, blacks were welcomed to spend their money, but Main Street was the “white folks street.” A minister and civil rights leader recalls that, “[when] we would walk down the street [and] a white person would come along, they would occupy the whole street. And, you had to get off to the side, wait, and let them pass.” An African-American woman remembers, “We would go uptown and purchase items from the 10-cent store and stuff, but everybody black would hang on ‘Nigger Street,’ which is Fair Street now.”

The local civil rights movement directly challenged white supremacy and the accompanying white sense of entitlement and private ownership of nominally public spaces. In Claiborne County, the obvious shifts in power triggered by the civil rights movement came through the political process and a black boycott of white merchants.

However, some of the most dramatic, visible confrontations over power came on Main Street as African Americans challenged white usurpation of such public spaces. For example, Jimmy Allen, a white merchant and member of the board of aldermen, parked vehicles from his car dealership on the sidewalk forcing pedestrians to walk around. Civil rights leader Charles Evers challenged this practice telling a crowd of marchers, “This street doesn’t belong to Allen. It belongs to the City of Port Gibson. That is all of us.”

White assumptions of jurisdiction over the streets is clear in another interaction involving a movement leader, Calvin Williams. Williams and an informal group of African Americans were walking down Main Street when they encountered the white chief of police and a group of white men who were standing together on a street corner. Although Williams and those accompanying him were simply walking down the street, Williams was arrested and charged with “disturbing the peace” and “blocking the public sidewalk and entrances to stores.” The white men who testified against him described how Williams and his companions were walking in a group down the street and at one point stopped on a corner. They never reported Williams actually physically blocking the sidewalk or any store entrance, and more importantly, saw no irony in the fact that they too were standing in a group on a sidewalk corner. Race and power were the only real differences between the two groups of men on Main Street that day.

But explicit white control of public streets was ending. That summer the Deacons for Defense and Justice, a group of armed black men, patrolled the streets of Port Gibson with guns and walkie talkies to ensure the protection of movement leaders, churches, and black citizens. Strong, armed, black men dressed in distinctive black hats, patrolling and standing on Main Street, created a powerful challenge to long-standing white dominance of the streets.

During the movement, individuals like Charles Evers, Calvin Williams, and the Deacons asserted their right to stand, march, or congregate on Main Street, while newly registered black voters replaced white officeholders, occupying the antebellum courthouse with black officeholders. Yet, to some extent, blacks simply moved into a white world symbolized by the courthouse and Main Street. While many stores went out of business and for years Main Street had the appearance of a ghost town, it still retained the feel and character of its white occupants and the remnants of the prized (by whites) antebellum culture.

Even today, whites still assume, maybe unconsciously, that their world view, their aesthetic, is the right one or even the only one. This summer, 30 years after the movement began, Mississippi Cultural Crossroads challenged that aesthetic and has laid claim to downtown Port Gibson at another level. By affirming African-American culture and vision, the mural project, including sidewalk and painted posts, is another step in establishing downtown public space for all Port Gibson residents. Not as confrontational as defiant speeches, changing behavior, and civil rights marches, art provides a more implicit challenge because it puts forth a vision which is not universal and which diverges from the unspoken or undefined. At stake this time are competing priorities and visions of Port Gibson and whether the entire community will share in a sense of belonging and commitment.

The bollards are now their original white, the mural is being continuously evaluated, and there is discussion and speculation about the fate of the painted sidewalk. This experience illustrates that historic preservation is not neutral or colorblind. It can too easily be used as a vehicle for returning to an imagined ideal of a bygone time.

Many whites believe historic preservation should recreate the image of pre-civil rights movement Main Street and antebellum mansions of a seemingly idyllic past. For African Americans these images recall the same era but to a different effect. The good old days of white memory are, for African Americans, colored by painful recollections of poverty, oppression, and capricious white power. This white-dominated vision doesn’t completely exclude African Americans, but encompasses them in a larger Jim Crow world where African-American cemeteries and shotgun houses are acceptable images of the past because they don’t challenge white historic vision. But MCC and the community mural refuse to accept this world view which would once again include blacks simply on white terms.

The white city clerk’s immediate reaction to the painted sidewalk (“Look what they’ve done to our sidewalk!”) was quite perceptive. She recognized that by painting the sidewalk, the school children and younger generation were putting their mark on a piece of Port Gibson and making it theirs.

Perhaps, too, in the same brush strokes, they were laying the groundwork for a truly integrated Port Gibson, one that their elders — tied to the past, years of racial struggle, and conventional visions of history — cannot visualize or imagine. While white adults, even unconsciously, recognize an assertion of African-American power in the mural, the white children who participated have a different experience and understanding. They now share something with their black coauthors. And, perhaps, in another 30 years, the white and black participants in this project will meet at the mural to show off to friends and family their shared history and tradition. If that happens, their parents’ stated ideal of a harmonious integrated community might come to pass, not through ignoring the community’s varied racial perspectives, culture, and history, but through embracing them.

Tags

Emilye Crosby

Emilye Crosby wrote her dissertation about the civil rights movement in Port Gibson, Mississippi, which was where she grew up. She is an assistant professor of history at State University of New York— Geneseo. Patty Crosby is her mother and director of Mississippi Cultural Crossroads. (1996)