Whiskey

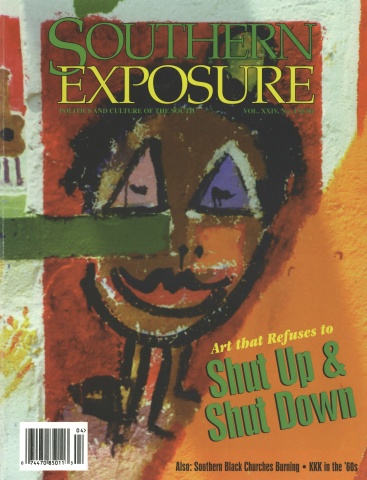

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

Deep in the soul of American whiskey lies the rich pioneer spirit that founded this nation, proclaim Gary Mardee Haidin Regan in The Book of Bourbon. “We think most good bourbons sound like Tom Waits; their harsh-sounding voices belie their caring hearts and deep, deep souls.”

While some Southerners may not find whiskey and its cousin bourbon quite so poetical, the brews have sat along side water jugs on Southern tables since Scotch-Irish immigrants brought stills over from the British Isles in the 1700s.

From the outset, whiskey was a kind of liquid gold. As immigrants moved further west in the late 18th century, it became hundreds of times more lucrative to distill rye or corn into liquor and ship it east in barrels rather than shipping it in its bulkier raw form. In the 1790s, high federal taxes on their successful enterprise spurred many western liquor producers to revolt. After the government quashed the Whiskey Rebellion, die-hard bootleggers settled in the hills of Kentucky and Tennessee, as far as they could get from meddling tax collectors.

Conditions in those two states were ideal for their work — plenty of corn, rye and barley, pure spring water, and oak trees for making barrels. Charring the oak staves and storing the liquor for at least two years gave ordinary whiskey the distinctive flavor that made it bourbon.

Over the years, strong drink has been used as a cure, a fluid for celebration, a form of payment, and a means of control. Southerners plied Native Americans with the liquor and withheld it from slaves. Churches preached for temperance while bootleggers got rich. Through taxes and politics, home brew remains a Southern tradition.

“When I was teenager, I knew where all the stills were up in the hollers,” says Peggy Morris, 52-year-old secretary to the commissioner of the West Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) Administration. Her father was a coal miner and her mother ran a boarding house. When she drove boarders up to find the stills, she encountered one family that piped the moonshine right into the kitchen sink for everyone to imbibe.

Southerners continue to make and drink their own liquor. A 1968 national survey found that over 12,000 illegal stills were seized in Southern states, compared to a couple hundred for the rest of the country.

In the ’90s the numbers are smaller, but there are still moonshiners around. In 1992, Alabama ABC officials said they were destroying about 95 stills a year. Morris says in West Virginia a lot of moonshiners hide their wares too carefully to track down, but some get caught. “There was a guy last year selling moonshine right behind his old grocery store for five dollars a pint,” she says. “Didn’t even think he was doing anything wrong.”

In addition to moonshine, Southerners consume more bourbon as a region than any other, with Texas, Florida, Kentucky, and North Carolina in the lead. Kentucky, the biggest bourbon producer, has also started exporting globally, and Japan has become one of the industry’s biggest customers. Bourbon bars (one with the name “Nashville”) have popped up all over Tokyo; the clientele can sip premium brands while Japanese musicians sing country-western tunes.

Bourbon may emigrate overseas, but it will never lose its Southern identity. Air South boosted its Southern image by offering bourbon and whiskey to passengers along with plenty of South Carolina peanuts. “In today’s competitive environment,” says a company representative, “you have to remind customers where they are.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)