This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

Some who wrote the local newspaper said that Larry Jens Anderson’s exhibit at the Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College in Gautier was an “abomination.” Others commended the school for bringing in the show about homosexuality and AIDS. School officials closed the exhibition early.

The shutting down of Anderson’s exhibition was one of more than a hundred cases of censorship across the nation last year. The children’s film, The Lion King and the popular Broadway play about people with AIDS, Angels in America, faced challenges. Television shows such as Seinfeld and Chicago Hope came under attack. Radio stations all over the country are giving into pressures to stop playing “gangsta rap” music.

Many of the high-profile campaigns are led by organized groups. “Don Wildmon [of American Family Association in Mississippi] accounts for a big share of the activity,” reported Matthew Freeman, director of research for People for the American Way, a Washington, D.C.-based organization devoted to defending freedom of expression. But challenges to commercial television, movies, music and advertisements accounted for just one-quarter of the censorship incidents. The rest were local and regional arts: plays, paintings, murals, and photo exhibits.

The sentiments of those objecting in the smaller venues are generally the same as Wildmon and his national group. “Eighty percent of the objections come from the political right,” according to Freeman. “In past years we saw a lot of incidents described as political correctness variety,” said Freeman. These were complaints that a work constituted harassment, for instance. But this year, Freeman said, that kind of challenge makes up only about 5 percent of all objections to art.

People for the American Way documented 137 challenges to artistic expression in 41 states and Washington, D.C. Those objecting to art, television shows, plays or other media “claimed it was pornographic or obscene, objected to depictions of faith, or on grounds it was promoting homosexuality,” said Freeman. Homosexuality was the biggest problem for viewers, he said, followed by objections to sexually explicit materials.

“Challengers continue to be remarkably successful at removing or restricting the expression to which they object,” reported PFAW in their annual listing of incidents, Artistic Freedom Under Attack. In nearly three-quarters of the cases, work was removed or restricted.

The South, with approximately a quarter of the nation’s population, accounts for nearly a third of the cases of censorship in the nation, according to Freeman.

There is more than one way to talk the arts into shutting up. Lack of funding has had a chilling effect on art and artists, especially in rural areas.

In the following portfolio, we focused on examples of publicly funded art or art shown in public places in the South.

Ironies, Controversies, and Community

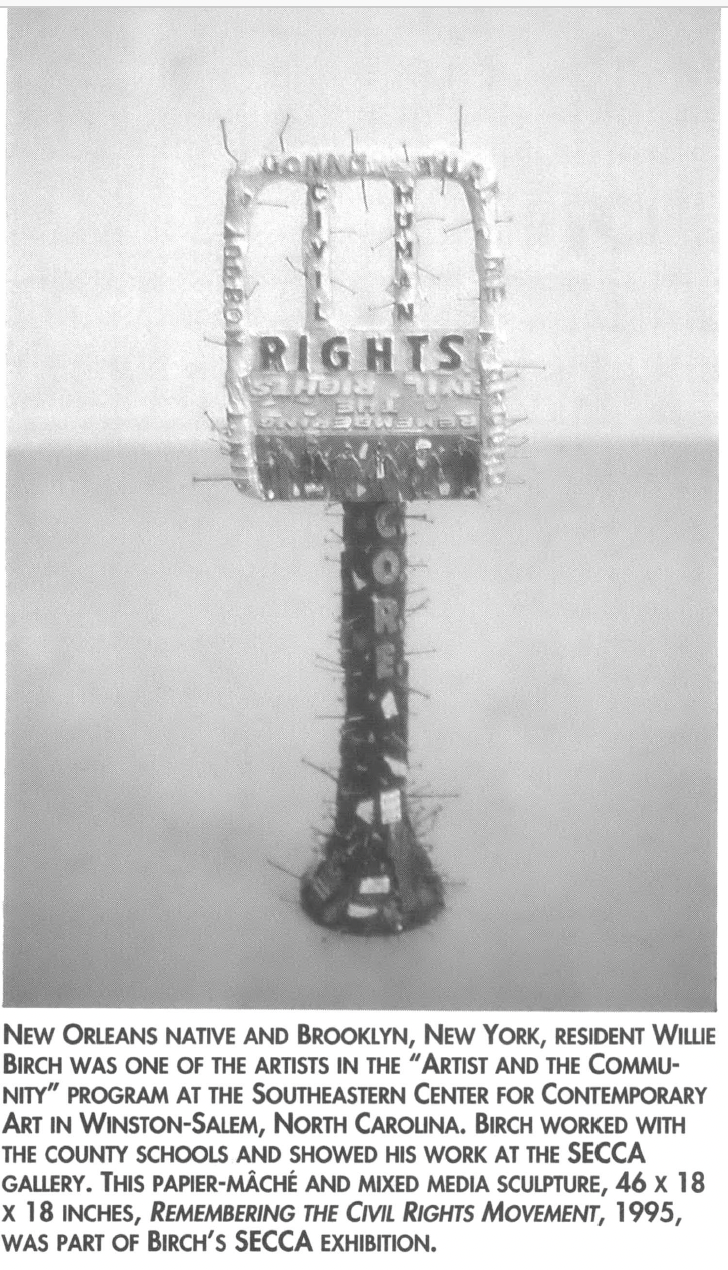

Southeastern Center for Contemporary Arts.

Winston-Salem, N.C. — Controversy over a photograph called “Piss Christ” had a chilling effect on the work of the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. But the flap also inspired the 40-year-old nonprofit visual arts organization to learn to work with the community and become more effective, according to its director.

“Piss Christ,” a photograph by artist Andres Serrano, featured a crucifix in a container of urine-like liquid. Serrano had created the work as part of a fellowship he received through a major 10-year-old SECCA program called Award for the Visual Arts. The program involved a show that traveled to various museums without incident in 1988.

That was before North Carolina’s Senator Jesse Helms noticed the piece. “He had gotten wind through the American Family Network,” said Virginia Rutter, SECCA’s public relations and marketing coordinator. Helms’ office asked for a catalog from the show, which Rutter provided.

“It dislodged the first rock in a landslide of congressional criticism of the National Endowment for the Arts, which supported . . . SECCA’s annual examination of new art in America,” wrote Steven Litt in the Raleigh News & Observer. In the summer of 1989, “Piss Christ,” along with Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos of nudes, some in sadistic and homo-erotic poses, became the focus of the crusade to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts.

Helms’ office “asked us to help bury the NEA,” said Rutter. “We said no.” Funding levels dropped, but the NEA survived.

The current director of SECCA, Susan Lubowsky Talbott, was, at the time of the controversy, director of the visual arts program at the NEA, which funded the Serrano project.

SECCA had sponsored the art program with funding from the NEA, the Rockefeller Foundation, and corporate sponsors. After the controversy, Talbott said she found it ironic that “the only funder willing to go on with the program was the NEA.” But SECCA could not find matching funds needed to secure the NEA grant. Rockefeller and the foundation had already made it clear before the controversy began that they weren’t planning to fund the program again, according to Talbott.

No other sponsor wanted to fund the program. “I could only guess that it had something to do with the Serrano controversy. We couldn’t make the match. I could not find the corporate support for it when I came on board in 1992.” The entire Award for the Visual Arts program had to be abandoned.

“That’s long behind SECCA,” Talbott said recently. “SECCA has been going about our business.”

Programs now involve community-based grassroots work. SECCA has succeeded, according to its director, in making a transition from “an institution under a great deal of attack because of Serrano to an institution that has been getting a great deal of support. Our whole Artists in the Community [program] has a lot of success stories.”

The programs and exhibits have not involved inflammatory images of nudity or religion, but they have had potential for problems, especially when they deal with race and gender issues, said Talbott. Many of the works “do question the basic core beliefs of a lot of people in this community. Some of the most activist artists have done exhibits here,” she said.

“We did an exhibit last year, ‘Civil Rights Now,’ and the curator felt very strongly that civil rights in the ’90s involved not only racial issues but gender issues and gay and lesbian rights, and one part of the show had the potential to be very controversial because it was extremely sexual in nature.”

Before the show opened, SECCA arranged a special showing for community leaders including blacks and whites, liberals and ultra-conservatives. “We asked them to see the show before we showed it to the public to give us advice on how to program the exhibit. About 25 came. Our curator and I gave them a tour.”

The strategy worked better than the staff expected. The show included large photos of Ku Klux Klan members by, ironically, Andres Serrano. A black alderwoman stood in front of one of these photos and talked about having a cross burned on her lawn as a girl. “Her description brought tears to every person there,” Talbott said. People in this diverse group talked to each other.

There was discomfort with the exhibit, too. Members of the black community were upset that gay rights were being mixed in with black civil rights. After listening to the opinions of the visitors, “We ended up rewriting some of our label copy, rewrote it in a more sensitive way,” said Talbott.

Seeing the work, airing opinions, and being heard made the difference. “Even a lesbian videotape was accepted by everyone there,” said Talbott.

The show came off without opposition or controversy. Taking the time to build a base of support in the community, “was a very different approach than the Serrano controversy, where no one wanted to hear the opposition.” Of course, Talbott added, “It was such a political football. It is not realistic to say that the kind of tactics we used with ‘Civil Rights Now’ would have worked on a national level, but I think the art world made a grave mistake — and myself as well — in taking a defensive, combative position that didn’t allow the opposition any integrity.”

The art world “took what I consider now to be a very elitist position that ‘you can’t understand art.’ All the arguments were made about the aesthetic qualities of the work, and the whole dialogue was very much art world language, artspeak. There was an us and them mentality.”

She said Jesse Helms and New York Republican Senator Alfonse D’Amato propagated the argument, but that the art world went on the defensive. Talbott was quick to say that she still supported NEA and freedom of expression, “but the argument can be made in a less elitist and less combative way and in a way that is based more on dialogue and mutual understanding than on animosity and the position of ‘we’re smart, you’re stupid.’”

Today, SECCA is comfortable in its revised role as a member of the community. Financially, they’ve never been better off. The center receives support from NEA and state and local foundations and agencies. This support has more than made up for other cutbacks and losses. “I daresay we’re not typical,” said Talbott. The Artist in the Community program is “the kind of thing that funders want to do now, but not every institution has that as their mission. We happen to be fitting right into the trend [that foundations like], so we’re lucky, but it’s the work we’d be doing anyway.”

The Offensive Human Body

Maxine Henderson

Murfreesboro, Tenn. — “It was really a semi-nude — she was draped at the bottom, and her arm was over her breast,” says Maxine Henderson, whose painting landed her in the midst of a First Amendment battle.

The nude, which the artist made with a palette knife and leftover paints at the end of a painting day, was one of 40 paintings in a one-woman show October 1995 in the rotunda of City Hall in this middle Tennessee town. Other images created by the retired businesswoman turned full-time painter included local churches, the woman’s club, and the artist’s grandchildren.

When the assistant superintendent of city schools passed the exhibit on her way to a meeting and saw the nude, she objected. “I personally find ‘art’ in any form whether it be a painting, a Greek statue or a picture out of Playboy which displays genitals, buttocks, and/or nipples of the human body to be pornographic and, in this instance, very offensive and degrading to me as a woman,” she said in a sexual harassment complaint she submitted to the city the next day.

The city removed the painting and changed policies to give the city manager final say in art exhibits.

Henderson felt she had to fight.

“They rewrote city art policy after this incident. My attorney calls it prior restraint. The art committee failed to stand up. I was just outraged,” said Henderson.

She has filed a federal lawsuit claiming her First Amendment rights were violated. “I felt that I had to as a citizen,” she said. She thought the complaint “trivialized the real issue of sexual harassment. So many people need this protection that it’s obscene she took this route.”

Demonic Symbols

Mona Waterhouse

Mobile, Ala. — “I’m from Sweden originally. I have lived all over America, and it never ceases to amaze me the way people think,” said artist Mona Waterhouse after the University of Mobile removed her work from a regional show last year for use of “demonic symbols.”

The university displayed “incredible ignorance,” she said recently as she explained what happened to her work. “In my paintings the symbols I used are based on rune stone symbols, the ancient way of writing before Christianity. That’s probably why I got in trouble.”

A jury selected Waterhouse’s piece, “Letters Home III” for an annual exhibition of Southern artists, “Art with a Southern Drawl,” at the private religious school.

The painter/sculptor/teacher used rune stone symbols, which are found in art and decoration all over Sweden, as symbols for her letters home once-a-week for the 35 years she has lived away from her native land. “They don’t mean anything,” she said, but they “represent everything that has been written, in a sense.”

A student who saw the show just before it was to open “totally freaked out, got a book about witchcraft — where did she get that, I wonder? — and told the director of the show that the work was demonic,” said the artist.

The director of the show, Charles M. Clark, who was also chair of the department of fine arts, “summoned some individuals affiliated with the University who could either confirm or deny the student’s interpretation and, unfortunately, they all concurred that the piece contained a number of demonic symbols,” according to a letter informing Waterhouse that her picture had been withdrawn from the exhibition. Clark and Audrey C. Eubanks, Vice President for Academic Affairs, both signed the letter.

“We do not know whether or not you were aware, at the time you submitted the piece, that the University of Mobile was created under the auspices of and is closely affiliated with the Alabama Baptist State Convention. In view of this affiliation, and the University’s Christian philosophy, we think you can understand that a piece containing such symbols is not appropriate for exhibition at any University facility or at any events sponsored by the University,” the letter explained.

They offered to let the painter submit another piece “with a content which would be more in keeping with the Christian philosophy of the University.” The artist refused.

She is still angry that the administration immediately took down the picture in reaction “to one student’s hysteria. For me it reflects much larger issues.” Acting out of fear and ignorance, “that’s where all the evil comes from, in my book.”

I Have to Watch What I Show

Isabel Zamora

Fort Worth, Texas — Isabel Zamora’s show at the Health Science Center at the University of North Texas featured two nudes, but the artist wasn’t much worried about offending anyone. After all, the display of her art for Hispanic Heritage Month was at a medical school, where “they see dead bodies,” so why would some nudes painted in a life-drawing class bother anyone?

A week after the show opened, exhibit organizer Sylvia Flores noticed that one of the pictures, a male nude, was missing. Thinking the work had been stolen, she called the artist who “began to panic.” Two days later, the drawing turned up in the office of equal employment officer Louis Seales. He had removed the drawing after he received a complaint from “an anonymous university staff member,” who claimed that the drawing “was obscene, sexually harassing, and potentially offensive to women and children visiting the center,” according to Artistic Freedom Under Attack 1996 by People for the American Way.

“That struck me as weird,” said Zamora, who recently graduated from the art program at Texas Wesleyan. “The drawing of the female nude was O.K. It was the male nude she found offensive.”

The show had about two weeks left to run, but Zamora took down the other nude as well, worried that it would be damaged.

She said she never received a real explanation or apology. The artist, who teaches fifth grade and creates religious works for area Catholic churches, speculated that her minority status might have acted as a catalyst for the people who objected to and removed her work. The sexism certainly struck her: “If we see men nude, it’s offensive, but you can go ahead and show a woman.”

Zamora noted the chilling effect on her work. “I feel that I have to watch what I show. I had that fear. I didn’t have the freedom to express myself.” The university has not asked her to exhibit work this year for Hispanic Heritage month as they had done in past years. She said she would not display her work there in any case because they had treated her so rudely.

Her religious work has been rewarding. The bishop blessed her and the painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe that she did for the Catholic diocese, and she continues to paint for the church.

Her priest was supportive when medical school officials removed her nude pictures from the exhibition last year. “The priest said, ‘God brought us into this world nude. Why shouldn’t we [see] nudes? People should appreciate the artist who draws what God created.’” He warned her that people can be close-minded, and to be careful where she shows her work. “He said, ‘You have to remember we’re in Texas.’”

No Shows at Home

The Road Company

Johnson City, Tenn. — Because funding has been so tight, the new show that The Road Company has been developing isn’t so new. Five performer/writers have been working on creating Zero Moment for more than three years. This year they hope to finish the script. Next year, they can think about performing their show about the lives of a band of sideshow performers.

A theater troupe based in a small Appalachian city creating original works is always going to have a tough time finding funding, but this lean nonprofit is learning to make do with even less than usual. The National Endowment for the Arts Expansion Arts Program ended in 1996, taking money the 20-year-old touring group used to put on plays at their home base. This year, The Road Company will present no shows at home and bring in no guest performers.

The performers did receive a $6,000 grant recently from another NEA program to finish Zero Moment. That limited funding will enable the group to write a script, not to develop the play the way they usually do — on their feet as an ensemble.

That funding along with teaching in artists-in-the-schools programs, and community arts center funding from a private donor to work with neighborhood children, will make up the $40,000 budget this year. In the past, when they had big projects — such as taking a show to Russia — their budget has been as high as $250,000.

The small core ensemble of two actors and a staff person, won’t let a lack of funding stop them from the work they do. They won’t be buying new cars, either. Or even new jeans. But they never have. They’ve always been content to work in this East Tennessee community creating and performing plays of their own design.

From Zero Moment

By The Road Company ensemble — Christine Murdock, Eugene Wolf, Ed Snodderly, Laurene Scalf, and Bob Leonard

Dog Boy Speaks in Tongues

They law, if that is not the awfullest thing I have ever seen. That boy is the vilest thing on the face of this earth. That boy invented evil. He’s as evil as cockroaches.

I don’t know what the big to-do is. Everybody thinks he’s so good-looking. Well, if he’s good-looking, I’m Joey Heatherton. Pshht. Everybody eats him up like buttermilk. I don’t know. There’s something funny about him. I don’t like him. I don’t. He’s creepy. And that girl. That old tramp that runs around here in them old dresses. They are brother and sister. Now, and I know it. They’ve got different last names, but they are brother and sister. They might have different daddies, or something.

Now she is pretty. She is, but she acts trashy. She’s went with every old thing in this town. You know a person’s actions will make a person look ugly to you. I don’t go down there, but they say she just kisses on everything at the Watering Hole. And her colors don’t look good on her. She ought to have that done, where they tell you what colors to wear. Of course, you know, she don’t wear anything too long. If you get where I’m going with that. . . .

Joe

I see a little girl on the tightrope. It is very early morning. No one else is around. The tent flaps in the early morning breeze. The air is close but hints of the warm to come. The little girl wears a pink dress. At the foot of the ladder, a little pair of white socks lie atop black patent leather Mary Janes. She moves slowly, thin arms out to her side for balance. She steps, teeters, waits until her footing is again secure. I hold my breath while she brings her right foot slowly around to the front of her left. Her tiny soles are pink, the toes indiscernible from this distance.

I could climb the ladder and grasp the tightrope, watch her little eyes bug with fear, watch her little mouth form a round pink scream as she falls. I could defile her. I have never been with a child. I’ve never thought of it till this moment. Her skin must be incredibly smooth. The thought is disgusting, thrilling. I look around the tent. I listen intently, dreading, hoping, to hear someone coming. No one.

As she moves across the wire, I move toward the ladder. We move in tandem, my slow step echoing hers. Neither of us breathes. I silently scale the ladder. As I reach the top, she turns her head. She is frozen there on the wire, one foot in front of the other, knees slightly bent, her arms stretched out like wings, her head turned to me. Her eyes are gray; their gaze is grave. I can’t look away from her eyes. I reach out to take the wire in my hand. Her mouth turns up at the comers in a tiny smile. She steps off the wire and flies away, away through the air, through the doorway, out of the tent.

I begin to breathe again. I realize where I am, standing near the top of the ladder, holding the wire in my hand. I let go of the wire and descend the ladder. When I get to the bottom, Dog Boy is standing there staring at me. He holds the little shoes and socks in his hands.

I run all the way home, looking behind me often to see if Dog Boy is following me. He isn’t, but I can’t slow down until I get to the cave. I throw myself on the stone and lie there panting. I keep seeing her step off the wire. And that tiny sweet smile just before she moved. It was a smile of pity, and remembering it fills my heart with hatred.

Tags

Pat Arnow

Pat Arnow, former editor of Southern Exposure and Now & Then, is a writer in Durham, N.C. (1999)

Pat Arnow, editor of Southern Exposure, wrote a play with Christine Murdock and Steve Giles, Cancell’d Destiny, that was featured at a ROOTS festival in 1990. (1996)

Pat Arnow is a writer and photographer who lives in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her short story, "Point Pleasant," was selected "best story" at the Hindeman Writers' Workshop in 1985. (1986)